From the Archives: Jerry Garcia ”” The Rolling Stone Interview

Reflections on the Grateful Dead’s relentless success and ever-growing catalog

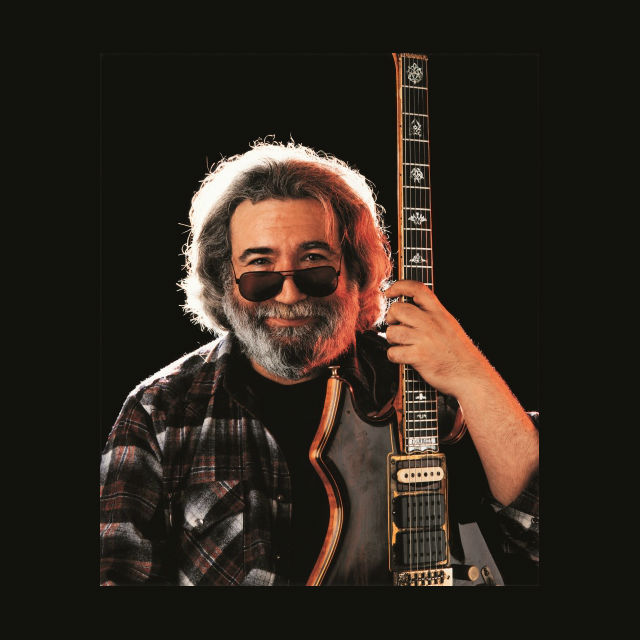

Jerry Garcia. Photo: Herb Greene/Bethel Woods Center

If there’s such a thing as a recession-proof band, the Grateful Dead must be it. While the rest of the music industry has suffered through one of its worst years ever ”” record sales have plummeted, and the bottom has virtually fallen out of the concert business ”” the Dead have trouped along, oblivious as ever to any trends, either economic or musical.

During the first half of the year, the group ”” now in its twenty-sixth year ”” grossed $20 million on the road. Over the summer, which experts have declared the worst in memory for the touring business, the Dead were the only band that chose to concentrate on ”” and, indeed, that filled ”” outdoor stadiums. Their average gross per show, according to the industry newsletter Pollstar, was more than $1.1 million, or nearly twice that of the summer’s second biggest touring act, Guns n’ Roses. And then, immediately after Labor Day, the Dead hit the road again, playing three nights at the Richfield Coliseum outside Cleveland, nine nights at New York City’s Madison Square Garden and six nights at the Boston Garden. All of the shows, of course, were sellouts.

Jerry Garcia, the group’s forty-nine-year-old singer-guitarist-songwriter, is as baffled as anyone by the Dead’s seemingly unstoppable success ”” though he continues to search for explanations. “I was thinking about the Dead and their success,” Garcia said on a September afternoon, as he sat in a hotel room overlooking New York’s Central Park. “And I thought that maybe this idea of a transforming principle has something to do with it. Because when we get onstage, what we really want to happen is, we want to be transformed from ordinary players into extraordinary ones, like forces of a larger consciousness. And the audience wants to be transformed from whatever ordinary reality they may be in to something a little wider, something that enlarges them. So maybe it’s that notion of transformation, a seat-of-the-pants shamanism, that has something to do with why the Grateful Dead keep pulling them in. Maybe that’s what keeps the audience coming back and what keeps it fascinating for us, too.”

Even as they’ve continued to pull the fans in to their live shows, the Dead have been busy with other projects over the past twelve months. Last September, the band released Without a Net, a two-CD live set culled from some of its 1989 and 1990 concerts. Then, this spring, the group issued One From the Vault. Another double CD, One From the Vault documents a now-legendary 1975 concert at San Francisco’s Great American Music Hall, where the band first performed its Blues for Allah album onstage. (One From the Vault II, the next release in what promises to be a continuing series of CDs from the Dead archives, is due in January. It features a pair of August 1968 shows from the Fillmore West, in San Francisco, and the Shrine Auditorium, in Los Angeles.)

In April, Arista Records put out Deadicated, an anthology of fifteen Dead songs performed by artists as diverse as Elvis Costello, Dwight Yoakam and Jane’s Addiction. Proceeds from the album are being donated to the Rainforest Action Network and to Cultural Survival. Both organizations will also benefit from the publication this month ofPanther Dream, a children’s book about the rain forest, written by Bob Weir, the Dead’s other singer-guitarist-songwriter, and his sister, Wendy Weir, who also illustrated it. (In addition, Mickey Hart, one of the group’s drummers, has collaborated with Fredric Lieberman onPlanet Drum: A Celebration of Percussion and Rhythm, which was just published by HarperCollins. An accompanying CD has also been released by Rykodisc.)

Meanwhile, Garcia has not been sitting by, idle. In July, he and mandolin player extraordinaire David Grisman released a lovely CD of all acoustic music, ranging from their take on the Dead’s “Friend of the Devil” to B.B. King’s trademark The Thrill Is Gone” to Irving Berlin’s “Russian Lullaby.” And last month, Arista issued Jerry Garcia Band, yet another live two-CD set. Heavy on cover versions, including the Beatles’ “Dear Prudence” and four Bob Dylan songs, the album features Garcia’s longtime side band, which now includes John Kahn on bass, David Kemper on drums and Melvin Seals on keyboards. The band will venture out on the road in November for a series of East Coast dates, including one night at Madison Square Garden.

Garcia admits that these solo jaunts are often more entertaining than his work with the Dead, and one gets the feeling that if he felt he could easily extricate himself from the Dead and his attendant responsibilities, he might just do it. Still, when pressed, Garcia claimed the Dead take precedence. “It’s still fun to do,” he said. “I mean, even at its very worst, there’s still something special about it. We’ve all put so much of our lives into it by now that it’s too late to do anything drastic.”

Nonetheless, Garcia believes the Dead are at a transitional point, a situation primarily brought about by the drug-related death of keyboard player Brent Mydland in July 1990. Mydland, who over the years had assumed a major share of the group’s songwriting duties, has been replaced by both Vince Welnick, a former member of the Tubes, and Bruce Hornsby, who has been sitting in with the band on the road but whose long-term commitment is uncertain.

During two separate interview sessions for this article, conducted during the band’s New York stand, Garcia talked at length about Mydland’s death, the current state of the Dead and his attitude toward drugs. He also spent a considerable amount of time discussing his family. His openness on that topic was in part due to his renewed relationship with his eighty-three-year-old aunt ”” the sister of his late father, Joe Garcia ”” which prompted him to explore his roots more thoroughly. In addition, Garcia has been playing the role of family man recently. He was accompanied on tour by his current companion, Manasha Matheson, and their young daughter, Keelin, and ”” as incongruous as it may seem ”” much of his free time was filled with such activities as visiting zoos and taking carriage rides in Central Park.

I heard there was a meeting recently, and you told the other band members that you weren’t having fun anymore, that you weren’t enjoying playing with the Dead. Did that actually happen?

Yeah. Absolutely. You see, the way we work, we don’t actually have managers and stuff like that. We really manage ourselves. The band is the board of directors, and we have regular meetings with our lawyers and our accountants. And we’ve got it down to where it only takes about three or four hours, about every three weeks. But anyway, the last couple of times, I’ve been there screaming, “Hey, you guys!” Because there are times when you go onstage and it’s just plain hard to do and you start to wonder, “Well, why the fuck are we doing this if it’s so hard?”

And how do the other band members feel?

Well, I think I probably brought it out into the open, but everybody in the band is in the same place I am. We’ve been running on inertia for quite a long time. I mean, insofar as we have a huge overhead, and we have a lot of people that we’re responsible for, who work for us and so forth, we’re reluctant to do anything to disturb that. We don’t want to take people’s livelihoods away. But it’s us out there, you know. And in order to keep doing it, it has to be fun. And in order for it to be fun, it has to keep changing. And that’s nothing new. But it is a setback when you’ve been going in a certain direction and, all of a sudden, boom! A key guy disappears.

You’re talking about Brent Mydland?

Yeah. Brent dying was a serious setback ”” and not just in the sense of losing a friend and all that. But now we’ve got a whole new band, which we haven’t exploited and we haven’t adjusted to yet. The music is going to have to take some turns. And we’re also going to have to construct new enthusiasm for ourselves, because we’re getting a little burned out. We’re a little crisp around the edges. So we have to figure out how we are going to make this fun for ourselves. That’s our challenge for the moment, and to me the answer is: Let’s write a whole bunch of new stuff, and let’s thin out the stuff we’ve been doing. We need a little bit of time to fall back and collect ourselves and rehearse with the new band and come up with some new material that has this band in mind.

Do you think you might stop touring for a year or so, like you did back in 1974?

That’s what we’re trying to work up to now. We’re actually aiming for six months off the road. I think that would be helpful. I don’t know when it will happen, but the point is that we’re all talking about it. So something’s going to happen. We’re going to get down and do some serious writing, some serious rehearsing or something. We all know that we pretty much don’t want to trash the Grateful Dead. But we also know that we need to make some changes.

You mentioned writing some new material. Why do the Dead seem to have such difficulty writing songs these days?

Well, I don’t write them unless I absolutely have to. I don’t wake up in the morning and say: “Jeez, I feel great today. I think I’ll write a song.” I mean, anything is more interesting to me than writing a song. It’s like “I think I’d like to write a song”¦. No, I guess I better go feed the cat first.” You know what I mean? It’s like pulling teeth. I don’t enjoy it a bit.

I don’t think I’ve ever actually written from inspiration, actually had a song just go bing! I only recall that happening to me twice ”” once was with “Terrapin” and the other was “Wharf Rat.” I mean, that’s twice in a lifetime of writing!

What about when you made Workingman’s Dead and American Beauty? Those two albums are full of great songs, and they both came out in 1970.

Well, Robert Hunter [Garcia’s lyricist] and I were living together then, so that made it real easy. Sheer proximity. See, the way Hunter and I work now is that we get together for like a week or two, and it’s like the classic songwriting thing. I bang away on a piano or a guitar, and I scat phrasing to him or lyrics, and he writes down ideas. And we try stuff.

Have you ever thought of making another album in that vein?

Oh, jeez, I’d love to. But it has to do with writing the stuff, and like I said, I’m about ready now to write a whole bunch of new stuff.

Why do you think the Dead have had such problems making good studio albums?

Well, I think we have made a few good ones. From the Mars Hotel was an excellent studio album. But since about 1970, the aesthetics of making good studio albums is that you don’t hear any mistakes. And when we make a record that doesn’t have any mistakes on it, it sounds fucking boring.

Also, I think we have a problem emoting as vocalists in the studio. And there’s a developmental problem, too. A lot of our songs don’t really stand up and walk until we’ve been playing them for a couple of years. And if we write them and try to record them right away, we wind up with a stiff version of what the song finally turns into.

Getting back to Brent, did you see his death coming?

Yeah, as a matter of fact we did. About six or eight months earlier, he OD’d and had to go to the hospital, and they just saved his ass. Then he went through lots of counseling and stuff. But I think there was a situation coming up where he was going to have to go to jail. He was going to have to spend like three weeks in jail, for driving under the influence or one of those things, and it’s like he was willing to die just to avoid that.

Brent was not a real happy person. And he wasn’t like a total drug person. He was the kind of guy that went out occasionally and binged. And that’s probably what killed him. Sometimes it was alcohol, and sometimes it was other stuff. When he would do that, he was one of those classic cases of a guy whose personality would change entirely, and he would just go completely out of control.

You think, “What could I have done to save this guy?” But as you go through life, people die away from you, and you have no choice but to rise to the highest level and look at it from that point of view, because everything else is really painful. And we’re old enough now where we’ve had a lot of people die out from under us. I mean, [artist] Rick Griffin just died.

I wanted to ask you about him.

Oh, God, what a most painful experience. I mean, he was one of those guys that you only get to see two or three times a year, but every time you do see him, you really enjoy it. That’s the kind of relationship I had with Rick Griffin. I mean, I really respect him as an artist. I’ve been a fan of his since the Sixties. And he was a real sweet person. And now I’m not gonna be able to look into those blue eyes”¦.

They had a memorial service for him, where his friends took his ashes out on surfboards ”” he was a surfer, you know ”” and they dunked his ashes in the ocean. And they had leis and flowers and all this beautiful stuff. His folks were there, and it was very lovely, and they were very satisfied. I mean, for me at this point, I’m just happy if someone dies with a minimum of pain and horror, if they don’t have to experience too much fear or anything. It’s always hard to deal with death, ’cause there you are, confronting the unconfrontable. And I’m not a religious person ”” I don’t have a lot of faith in the hereafter or anything”¦.

Several people have told me that the Dead organization is difficult for a newcomer to deal with, that if you’re an insecure person, you’re not going to get much comfort.

No, forget it. If you’re looking for comfort, join a club or something. The Grateful Dead is not where you’re going to find comfort. In fact, if anything, you’ll catch a lot of shit. And if you don’t get it from the band, you’ll get it from the roadies. They’re merciless. They’ll just gnaw you like a dog. They’ll tear your flesh off. They can be extremely painful.

I heard that Brent never really felt like he fit in.

Brent had this thing that he was never able to shake, which was that thing of being the new guy. And he wasn’t the new guy; I mean, he was with us for ten years! That’s longer than most bands even last. And we didn’t treat him like the new guy. We never did that to him. It’s something he did to himself. But it’s true that the Grateful Dead is tough to”¦I mean, we’ve been together so long, and we’ve been through so much, that it is hard to be a new person around us.

But Brent had a deeply self-destructive streak. And he didn’t have much supporting him in terms of an intellectual life. I mean, I owe a lot of who I am and what I’ve been and what I’ve done to the beatniks from the Fifties and to the poetry and art and music that I’ve come in contact with. I feel like I’m part of a continuous line of a certain thing in American culture, of a root. But Brent was from the East Bay, which is one of those places that is like nonculture. There’s nothing there. There’s no substance, no background. And Brent wasn’t a reader, and he hadn’t really been introduced to the world of ideas on any level. So a certain part of him was like a guy in a rat cage, running as fast as he could and not getting anywhere. He didn’t have any deeper resources.

My life would be miserable if I didn’t have those little chunks of Dylan Thomas and T.S. Eliot. I can’t even imagine life without that stuff. Those are the payoffs: the finest moments in music, the finest moments in movies. Great moments are part of what support you as an artist and a human. They’re part of what make you a human. What’s been great about the human race gives you a sense of how great you might get, how far you can reach. I think the rest of the guys in this band all share stuff like that. We all have those things, those pillars of greatness. And if you’re lucky, you find out about them, and if you’re not lucky, you don’t. And in this day and age in America, a lot of people aren’t lucky, and they don’t find out about those things.

It was heartbreaking when Brent died, because it seemed like such a waste. Here’s this incredibly talented guy ”” he had a great natural melodic sense, and he was a great singer. And he could have gotten better, but he just didn’t see it. He couldn’t see what was good about what he was doing, and he couldn’t see himself fitting in. And no amount of effort on our part could make him more comfortable.

When it comes to drugs, I think the public perception of the Dead is that they are into pot and psychedelics ”” sort of fun, mind-expansion drugs. Yet Brent died of a cocaine and morphine overdose, and you also had a long struggle with heroin. It seems to run counter to the image of the band.

Yeah, well, I don’t know. I’ve been round and round with the drug thing. People are always wanting me to take a stand on drugs, and I can’t. To me, it’s so relativistic, and it’s also very personal. A person’s relationship to drugs is like their relationship to sex. I mean, who is standing on such high ground that they can say: “You’re cool. You’re not.”

For me, in my life, all kinds of drugs have been useful to me, and they have also definitely been a hindrance to me. So, as far as I’m concerned, the results are not in. Psychedelics showed me a whole other universe, hundreds and millions of universes. So that was an incredibly positive experience. But on the other hand, I can’t take psychedelics and perform as a professional. I might go out onstage and say, “Hey, fuck this, I want to go chase butterflies!”

Does anyone in the Dead still take psychedelics?

Oh, yeah. We all touch on them here and there. Mushrooms, things like that. It’s one of those things where every once in a while you want to blow out the pipes. For me, I just like to know they’re available, just because I don’t think there’s anything else in life apart from a near-death experience that shows you how extensive the mind is.

And as far as the drugs that are dead enders, like cocaine and heroin and so forth, if you could figure out how to do them without being strung out on them, or without having them completely dominate your personality”¦I mean, if drugs are making your decisions for you, they’re no fucking good. I can say that unequivocally. If you’re far enough into whatever your drug of choice is, then you are a slave to the drug, and the drug isn’t doing you any good. That’s not a good space to be in.

Was that the case when you were doing heroin?

Oh, yeah. Sure. I’m an addictive-personality kind of person. I’m sitting here smoking, you know what I mean? And with drugs, the danger is that they run you. Your soul isn’t your own. That’s the drug problem on a personal level.

How long were you doing heroin?

Oh, jeez. Well, on and off, I guess, for about eight years. Long enough, you know.

Has it been difficult for you to leave heroin behind?

Sure, it’s hard. Yeah, of course it is. But my real problem now is with cigarettes. I’ve been able to quit other drugs, but cigarettes”¦Smoking is one of the only things that’s okay. And in a few years it won’t be okay. They’re closing the door on smoking. So now I’m getting down to where I can only do one or two things anymore. My friends won’t let me take drugs anymore, and I don’t want to scare people anymore. Plus, I definitely have no interest in being an addict But I’m always hopeful that they’re going to come up with good drugs, healthy drugs, drugs that make you feel good and make you smarter.

Smart drugs.

Yeah, right. Exactly.

Have you tried smart drugs?

I tried a couple of things that are supposed to be good for your memory and so forth, but so far I think that, basically, if you get smart about vitamins and amino acids and the like, you can pretty much synthesize all that stuff yourself. Most of the smart drugs I’ve tried have had no effect, and the ones that did have an effect, it was so small it was meaningless. I mean, if there really was a smart drug, I’d take it right now. “That’s really going to make me smart? No shit? Give me that stuff!”

But I still have that desire to change my consciousness, and in the last four years, I’ve gotten real seriously into scuba diving.

Really?

Yeah. For me, that satisfies a lot of everything. It’s physical, which is something I have a problem with. I can’t do exercise. I can’t jog. I can’t ride a bicycle. I can’t do any of that shit. And at this stage of my life, I have to do something that’s kind of healthy. And scuba diving is like an invisible workout; you’re not conscious of the work you’re doing. You focus on what’s out there, on the life and the beauty of things, and it’s incredible. So that’s what I do when the Grateful Dead aren’t working ”” I’m in Hawaii, diving.

You became a father again a few years ago. How has fatherhood been this time around?

Well, at this time in my life I wasn’t exactly expecting it, but this time I have a little more time to actually be a father. My other daughters have all been very good to me, insofar as they’ve never blamed me for my absentee parenting. And it was tough for them, really, because during the Sixties and Seventies, I was gone all the time. But they’ve all grown up to be pretty decent people, and they still like me. We still talk. But I never did get to spend a lot of time with them. So this one I’m getting to spend more time with, and that’s pretty satisfying.

How old is Keelin?

She’s going to be four in December. She’s just at the point where animals are a burning passion for her. I took her to the zoo in Cleveland, and I had a lot of fun, feeding the animals and letting the tiger smell my hand and that stuff. And she loves the squirrels and the little birds. She got to feed a giraffe and things like that, so it was fun for her.

She also loves music. She loves to dance, and she loves to sing. She makes up songs furiously. And she has incredible concentration. She builds things. She calls them arrangements. She takes all her stuff and organizes it according to some interior logic. And she works on it for hours and hours. She’s really focused. Then she brings me in to look at it, and she walks around it and points things out. And sometimes all the bunnies will be together, looking out at you. Or the horses or something. And sometimes the logic defies you. But the way she focuses on it makes me think she’s going to do something ”” you know, that focus, it’s genetic or something. That’s the way I learned to play guitar, even though I’m not a particularly disciplined person. But she’s got it real heavy. I don’t know where she’s going to go with it, or what she’s going to do with it, but she’s sure going to make somebody really crazy [laughs].

Have any of your other kids shown an interest in music?

Yeah, Heather, my oldest daughter from my first marriage, is now a concert violinist. And that’s, like, with no input from me. Her mom, Sara Katz, tells me that she never particularly encouraged it, either. I actually got together with Heather for the first time in a long, long time ”” I hadn’t seen her in like eighteen or nineteen years ”” and I took her to see my friend David Grisman and Stephane Grappelli, and she loved it. So I hope it’s the beginning of something.

It’s a funny thing when you have kids. I just relate back to my own past, and I know I still basically feel like a kid, and I feel that anyone who looks like an adult is somebody older than me ”” although I’m actually older than them now. It’s a weird thing. My kids seem to be more mature and older than I am now somehow. They’ve gotten ahead of me somehow. But they’re very patient with me.

How old is your oldest daughter?

Heather is twenty-seven. I mean, I have people in the audience now who are younger than she is.

You also had two daughters with Mountain Girl, right?

Yeah, Trixie, who’s just turned seventeen, and Annabelle, who’s twenty-one. Annabelle has always had a good ear, but she’s not very interested in music. She’s like a computer-graphics person; she draws and designs stuff. And Trixie ”¦ Trixie is beautiful. It’s, like, where didthat come from? She’s really a howling knockout, a very pretty little girl.

So are you and Mountain Girl now divorced?

We’re working on it. We’re in the process of it, but it’s been going on for some time. She’s real glad to get rid of me. We had a great time, a nice life together, but we went past it. She’s got a life of her own now. Actually, we haven’t really lived together since the Seventies.

Your father, Joe Garcia, was also a musician, wasn’t he?

Yeah, that’s right. I didn’t get a chance to know him very well. He died when I was five years old, but it’s in the genes, I guess, that thing of being attracted to music. When I was little, we used to go to the Santa Cruz Mountains in the summer, and one of my earliest memories is of having a record, an old 78, and I remember playing it over and over on this wind-up Victrola. This was before they had electricity up there, and I played this record over and over and over, until I think they took it from me and broke it or hid it or something like that. I finally drove everybody completely crazy.

What instrument did your father play?

He played woodwinds, clarinet mainly. He was a jazz musician. He had a big band ”” like a forty-piece orchestra ”” in the Thirties. The whole deal, with strings, harpist, vocalists. My father’s sister says he was in a movie, some early talkie. So I’ve been trying to track that down, but I don’t know the name of it. Maybe I’ll be able to actually see my father play. I never saw him play with his band, but I remember him playing me to sleep at night. I just barely remember the sound of it. But I’m named after Jerome Kern, that’s how seriously the bug bit my father.

How did he die?

He drowned. He was fishing in one of those rivers in California, like the American River. We were on vacation, and I was there on the shore. I actually watched him go under. It was horrible. I was just a little kid, and I didn’t really understand what was going on, but then, of course, my life changed. It was one of those things that afflicted my childhood. I had all my bad luck back then, when I was young and could deal with it.

Like when you lost your finger?

Yeah, that happened when I was about five, too. My brother Tiff and I were chopping wood. And I would pick up the pieces of wood, take my hand away, pick up another piece, and boom! It was an accident. My brother felt perfectly awful about it.

But we were up in the mountains at the time, and my father had to drive to Santa Cruz, maybe about thirty miles, and my mother had my hand all wrapped up in a towel. And I remember it didn’t hurt or anything. It was just a sort of buzzing sensation. I don’t associate any pain with it. For me, the traumatic part of it was after the doctor amputated it, I had this big cast and bandages on it. And they gradually got smaller and smaller, until I was down to like one little bandage. And I thought for sure my finger was under there. I just knew it was. And that was the worst part, when the bandage came off. “Oh, my God, my finger’s gone.” But after that, it was okay, because as a kid, if you have a few little things that make you different, it’s a good score. So I got a lot of mileage out of having a missing finger when I was a kid.

What did your mother do for a living?

She was a registered nurse, but after my father died, she took over his bar. He had this little bar right next door to the Sailor’s Union of the Pacific, the merchant marine’s union, right at First and Harrison, in San Francisco. It was a daytime bar, a working guy’s bar, so I grew up with all these guys who were sailors. They went out and sailed to the Far East and the Persian Gulf, the Philippines and all that, and they would come and hang out in the bar all day long and talk to me when I was a kid. It was great fun for me.

I mean, that’s my background. I grew up in a bar. And that was back in the days when the Orient was still the Orient, and it hadn’t been completely Americanized yet. They’d bring back all these weird things. Like one guy had the world’s largest private collection of photographs of square-riggers. He was an old sea captain, and he had a mint-condition 1947 Packard that he parked out front. And he had a huge wardrobe of these beautifully tailored double-breasted suits from the Thirties. And he’d tell these incredible stories. And that was one of the reasons I couldn’t stay in school. [Garcia dropped out of high school after about a year.] School was a little too boring. And these guys also gave me a glimpse into a larger universe that seemed so attractive and fun and, you know, crazy.

But there were a couple of teachers who had a big impact on you, weren’t there?

I had a great third-grade teacher, Miss Simon, who was just a peach. She was the first person who made me think it was okay to draw pictures. She’d say, “Oh, that’s lovely,” and she’d have me draw pictures and do murals and all this stuff. As soon as she saw I had some ability, she capitalized on it. She was very encouraging, and it was the first time I heard that the idea of being a creative person was a viable possibility in life. “You mean you can spend all day drawing pictures? Wow! What a great piece of news.”

She enlarged the world for me, just like the sailors did. I had another good teacher, Dwight Johnson. He’s the guy that turned me into a freak. He was my seventh-grade teacher, and he was a wild guy. He had an old MG TC, you know, beautiful, man. And he also had a Vincent Black Shadow motorcycle, the fastest-accelerating motorcycle at the time. And he was out there. He opened lots and lots of doors. He’s the guy that got me reading deeper than science fiction. He taught me that ideas are fun. And he’s alive somewhere. I ran into some guys not long ago who said Dwight Johnson’s alive and is teaching down in Southern California, Santa Barbara or something. He’s one of those guys I’d like to say hello to, ’cause he’s partly responsible for me being here.

With the Dead and especially with your own band, you tend to cover a lot of Dylan tunes. What is it about his material that attracts you?

You can sing them without feeling like an idiot. Most songs are basically like love songs, and I don’t feel like I’m exactly the most romantic person in the world. So I can only do so many love songs without feeling like an idiot. Dylan’s songs go in lots of different directions, and I sing some of his songs because they speak to me emotionally on some level. Sometimes, I don’t even know why. Like that song “Señor.” There’s something so creepy about that song, but it’s very satisfying in a weird sort of way. Not that I know anything about it, because you listen to the lyrics, and you go, “What the hell is this?” But there’s something about it emotionally that says: This is talking about a kind of desperation that everybody experiences. It’s like Dylan has written songs that touch into places people have never sung about before. And to me that’s tremendously powerful. And also, because he’s an old folkie, he sometimes writes a beautiful melody. He doesn’t always sing it, but it’s there. So that combination of a tremendously evocative melody and a powerful lyric is something you can do without feeling like an idiot.

I have a real problem with that standing onstage anyway. I feel like an idiot most of the time. It’s like getting up in front of your senior class and making a speech. Basically, when you get up in front of a lot of people, you feel like an idiot. There’s no getting around that, and so a powerful song provides powerful armor.

You, Bruce Hornsby, Branford Marsalis and Rob Wasserman recently recorded the music for a series of Levi’s ads, directed by Spike Lee.

Yeah, we figured, hey, if Spike Lee could sell out, we could sell out. What the hell.

Do you enjoy playing with those guys?

I love it, any chance I get. I mean, for those ads, we just fucked around, really. They mixed the music so far back that you can just barely recognize us. You can almost make out Branford. I mean, you can’t hear me or Bruce.

Do you ever feel like you have more fun playing with those guys than with the Dead?

Oh, sure. Absolutely. And that’s always dangling in front of me, the thing of, well, shit, if I was on my own, God, I could”¦But the thing is, the Grateful Dead is unique. It’s not like anything else. I mean, there are lots of great musicians in the world, and I get to play with the ones who want to play with me, at least. And that’s important to me. I mean, Bruce, Branford, Rob Wasserman and I have actually talked about putting something together. I had this notion of putting together a band that had no material, that just got onstage and blew. And maybe one of these days, we’ll make that happen.

Hornsby seems to be taking a major role onstage with the Dead these days.

Well, he’s certainly been pushing me. He’s got great ears. And I also have a hard time losing him. I try, “Hey, Bruce, follow this.” But he’s there all the time. He also has a good sense of when not to play. And he’s got a great rhythmic feeling.

So is he a full-time member of the band?

Well, he’s acting like it. It’s a wonderful gift to the band to have him in it now. It’s a lucky break for us.

You mentioned “Wharf Rat” earlier. What do you think of the Midnight Oil version on the Deadicated album?

I think it’s terrific. That record is full of wonderful surprises.

What other tracks do you like?

I like “Ripple” by Jane’s Addiction. And I really like “Friend of the Devil” by Lyle Lovett. Very tasty. And the Indigo Girls and Suzanne Vega I really like. And it was very flattering to me to have Elvis Costello, who I think is just a real dear guy and a serious music lover, do one of our songs.

What other music are you listening to these days?

All kinds of stuff. I listen to anything anyone gives me. I always go back to a few basic favorites. I can always listen to Django Reinhardt and hear something I haven’t heard before. I like to listen to Art Tatum and Coltrane and Charlie Parker. Those are guys who never seem to run out of ideas. And there are all kinds of great new players. Michael Hedges is great. And my personal favorite lately is this guy Frank Gambale, who’s been playing with Chick Corea for the past couple of years.

What about pop music or, say, a band like Living Colour?

Living Colour is a great band. Their whole approach is interesting, but they’re short on melodies. And unless they find something with more melody, they’re going to have a hard time getting to that next level. That’s a tough space where they are right now; I think the most talented guy in the band is going to look to break out if the band doesn’t go somewhere.

Jane’s Addiction is another band I like. A great band.

You turn fifty next year. How does that feel?

God, I never thought I’d make it. I didn’t think I’d get to be forty, to tell you the truth. Jeez, I feel like I’m a hundred million years old. Really, it’s amazing. Mostly because it puts all the things I associate with my childhood so far back. The Fifties are now like the way I used to think the Twenties were. They’re like lost in time somewhere back there.

And I mean, here we are, we’re getting into our fifties, and where are these people who keep coming to our shows coming from? What do they find so fascinating about these middle-aged bastards playing basically the same thing we’ve always played? I mean, what do seventeen-year-olds find fascinating about this? I can’t believe it’s just because they’re interested in picking up on the Sixties, which they missed. Come on, hey, the Sixties were fun, but shit, it’s fun being young, you know, nobody really misses out on that. So what is it about the Nineties in America? There must be a dearth of fun out there in America. Or adventure. Maybe that’s it, maybe we’re just one of the last adventures in America. I don’t know.