‘The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan’: Inside His First Classic

Dylan broke with folk orthodoxy, recorded his own songs and made a masterpiece

Bob Dylan, Aust Ferry, England. Photo: Paul Townsend/Flickr

“I wrote a lot of songs in a quick amount of time,” said Bob Dylan of the creative explosion that resulted in his second album, 1963’s The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan. “I could do that then, because the process was new to me. I felt like I’d discovered something no one else had ever discovered, and I was in a sort of an arena artistically that no one else had ever been in before ever.”

Dylan’s second LP was not only his first genuine masterpiece, it was also a landmark in the very way that popular music was created. After writing just two songs on his 1962 debut, he wrote 12 of the 13 songs on Freewheelin’ ”“ including such classics as “Blowin’ in the Wind,” “A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall” and “Don’t Think Twice, It’s All Right” ”“ permanently altering the relationship between singer and songwriter. And he did so with a collection of compositions that displayed a dizzying range, from blistering social commentary (tackling such topics as civil rights and nuclear holocaust) to nuanced romance, from comic talking blues to melancholy heartbreak.

Unlike his debut LP (and unlike most of his albums to follow), Freewheelin’ was a project that Dylan, just 20 years old when recording began, took his time with. Where Bob Dylan was cut in just two days, this album was crafted over no fewer than eight separate visits to the studio, spanning a full year from April 1962 to April 1963. Over the course of those months, he continued to revise and refine the song selection, trying desperately to keep up with the breathtaking, high-speed evolution of his writing.

Though the world didn’t know it yet, Dylan had been writing songs nonstop since arriving in New York in 1961. “He was writing all the time, at night sitting in the clubs,” says Peter Yarrow. “You’d see him reading a newspaper, and then the next day he wrote a song about what he had read.

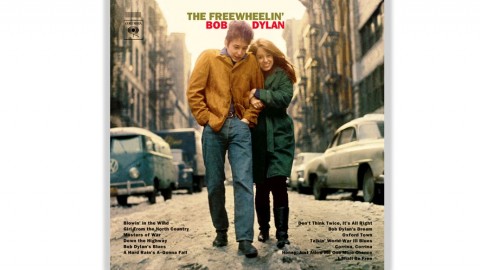

Bob Dylan | Photo Credit: Sony Music

The album was also informed by the constant influx of new experiences and ideas affecting Dylan at the time ”“ a burgeoning political awareness, his first trip overseas, the entrance of Albert Grossman as his manager. Above all, though, Freewheelin’ revealed the impact of his girlfriend Suze Rotolo, depicted huddling with Dylan on a snow-covered Jones Street for the album’s iconic cover. (“The cover’s the most important part of the album,” he would say to his friends.)

Rotolo was studying art in Italy during most of the album’s creation, and Dylan’s longing, even his anger, during her absence impacted many of these songs. Also crucial was the effect of Rotolo’s activist family on Dylan’s worldview; both of her parents were members of the American Communist Party. Suze “was into this equality-freedom thing long before I was,” he said.

In April, just a month after the release of his debut, Dylan first entered Columbia’s Studio A in New York to start work on an album then being called Bob Dylan’s Blues. Over the course of two days, he demonstrated his intent to build an album around his own writing, recording eight new original compositions along with several traditional folk songs and numbers by Hank Williams and Robert Johnson.

He returned to the studio July 9th, recording the loose,”¨ absurd “Bob Dylan’s Blues,” “Down the Highway” (which included the only explicit reference to Rotolo’s travels ”“ “My ”¨baby took my heart from me/She packed it all up in a suit”¨case/Lord, she took it away to Italy, Italy”) and “Honey, Just”¨ Allow Me One More Chance.” Most notably, though, in this”¨ session he recorded a song that he had debuted at Gerde’s ”¨Folk City in April, built on the melody of the old spiritual “No More Auction Block” ”“ a song titled “Blowin’ in the Wind.”

The simple majesty of the lyrics, a series of imagistic questions that added up to a forceful plea for common-sense justice and equality, was unprecedented. “The first way to answer these questions in the song is by asking them,” he told Nat Hentoff for the album’s liner notes. “But lots of people have to first find the wind.”

Grossman played a demo of the song for his clients Peter, Paul and Mary. “I immediately said, ‘This is it, this is the anthemic song,'” says Peter Yarrow. “It was such a breakthrough, it was absolutely astonishing.”

Peter, Paul and Mary would release “Blowin’ in the Wind” as a single three weeks after Freewheelin’ came out. It sold 300,000 copies in the first week of release, and it peaked at Number Two on the Billboard chart.

More recording sessions in October and November illustrated that Dylan still hadn’t settled on the proper shape for the album. He tried a new direction, recording with a full band in a style that flirted with rockabilly (almost three full years before “going electric”). The only tracks that ultimately made it to Freewheelin’ were his rewrite of the Mississippi Sheiks’ “Corrina, Corrina” and the breezily bitter “Don’t Think Twice, It’s All Right,” written after he heard from Rotolo that she was considering extending her stay in Italy.

“It isn’t a love song,” Dylan told Hentoff. “It’s a statement that maybe you can say to make yourself feel better.”

Three more keepers were added on December 6th, as the album was finally starting to come into focus. “Oxford Town” was an account of James Meredith’s ordeal as the first black student enrolled at the University of Mississippi, and “I Shall Be Free” was a bit of a throwaway, a rewrite of Lead Belly’s “We Shall Be Free.” This session also yielded the album’s greatest moment, the brilliant epic “A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall,” based on the melody and structure of the British folk ballad “Lord Randall.”

Dylan had premiered the song at Carnegie Hall on September 22nd, but exactly one month later, President Kennedy announced the discovery of Soviet missiles in Cuba, prompting the Cuban Missile Crisis. Never one to miss a chance for some self-mythologizing, Dylan told Hentoff that “Hard Rain” was written as a response to the threat of apocalypse: “Every line in it is actually the start of a whole new song. But when I wrote it, I thought I wouldn’t have enough time alive to write all those songs so I put all I could into this one.”

Allen Ginsberg said that when he first heard the song, he wept with joy because “it seemed that the torch had been passed to another generation. From earlier bohemian, or Beat illumination. And self-empowerment.”

As he kept working, Dylan told friends that he still wasn’t satisfied with where the album was going. “There’s too many old-fashioned songs in there, stuff I tried to write like Woody,” he said. “I’m goin’ through changes. Need some more finger-pointin’ songs in it, ’cause that’s where my head’s at right now.” The first manifestation was the scathing anti-military-industrial-complex attack “Masters of War.”

In April 1963, he got this new batch of songs recorded. “Girl From the North Country” was a wistful love song seemingly inspired by old girlfriends Echo Helstrom and Bonnie Beecher as much as his recent yearning for Rotolo, who had just returned to New York. “Bob Dylan’s Dream” also had a nostalgic streak, reflecting on friendships and a community that perhaps Dylan sensed would be forever altered after this album came out.

“We were just kids,” says Yarrow. “We were just putting one foot in front of the other, thinking about what we were going to have for dinner. I remember Bobby had this bullwhip and we would go out on the street and practice cracking the whip. ‘Bob Dylan’s Dream’ really captures all that.”

Those songs weren’t initially part of The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan, though; they were included later when Dylan got a chance to revise the album, most likely in response to his label’s demand that he remove the potentially libelous “Talkin’ John Birch Paranoid Blues.”

Regardless of the chronology, the result was an album that was better-rounded and more fully realized, replacing the reverence of more traditional folk blues with greater levity and depth.

Not that all of his earlier fans were ready to follow him. “The album floats away into never-never land, a failure,” wrote his Minnesota friends in the folk-purist journal The Little Sandy Review.

But around the world, the reverberations of The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan were enormous. In Winnipeg, Manitoba, a kid named Neil Young heard the album and, as with so many others, considered entirely new possibilities for his life. “I just said, ‘Hey, there’s a guy who sounds different doing his thing, too ”“ I really like this guy. I can write songs.'”