Tim Burton Gives ‘Big Eyes’ the Sheen of a Fable Laced with Menace

Waif painter Margaret Keane finally gets her due, courtesy of Tim Burton and Amy Adams

[rating=2.5]

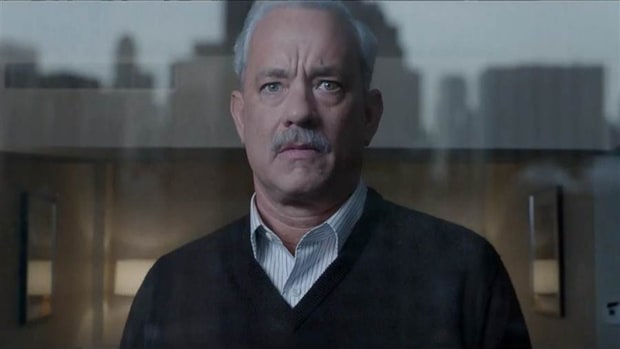

Big Eyes | Amy Adams, Christoph Waltz | Directed by Tim Burton

Amy Adams is picture perfect as Margaret Keane, a stifled artist who might have remained just another unhappy 1950’s housewife if she didn’t get up the gumption to give the boot to her lying husband, Walter (Christoph Waltz). It was Margaret who painted those portraits of sad, saucer-eyed waifs that left art critics cold. It was Walter who marketed his wife’s so-called low art into a jackpot industry. What ruffled Margaret was that Walter took credit for painting them, and worse that for years she let him. “People don’t buy lady art,” Walter told her.

Big Eyes could have been a dutiful Lifetime movie about the exploitation of women. That it becomes something scrappier, deeper and memorably comic and touching is due to the radiant Adams, who never patronizes Margaret, and to director Tim Burton, who gives the film the sheen of a fable laced with menace. For Burton, Big Eyes serves as a bookend to his masterful 1994 movie Ed Wood, also written by Scott Alexander and Larry Karaszewski, and also a monument to kitsch art triumphant.

What’s a girl to do? With her ex threatening a custody battle, she marries Walter, who persuades hungry i nightclub owner Enrico Banducci (Jon Polito) to show off Margaret’s paintings in his famed establishment, right near the toilets. Margaret’s work really takes off when Walter hits on the idea of selling them, cheaply, as posters and calendars.

The conflict kicks in when the womanizing Walter becomes increasingly abusive and Margaret leaves him, setting up shop in Hawaii, becoming a Jehovah’s Witness and spilling the truth on a 1970 radio in interview that she’s the only painter in the family. All this leads to a hilarious trial sequence in which Margaret and the inglorious bastard must paint in front of the judge. Burton turns the spectacle of watching Walter squirm into crowdpleasing fun without skimping on the human toll taken on a woman forced to lead a shadow existence.

Waltz hams it up in high style, though a little more restraint would have made Margaret seem less a dupe for falling for a man whose only artistry is the con. It’s Adams who restores our rooting interest by showing us the steel even in Margaret’s reserve. It’s a performance of haunting transparency.

It’s clear that Burton sympathizes, minus irony, with Margaret’s fervent belief in what one critic calls “the big, stale jellybeans” she puts on canvas. A recent showing of Burton’s artwork at New York’s Museum of Modern Art attracted long lines and critical brickbats. Maybe that’s why Big Eyes, for all its tonal shifts and erratic pacing, seems like Burton’s most personal and heartfelt film in years, a tribute to the yearning that drives even the most marginalized artist to self expression no matter what the hell anyone thinks. Walter died in 2000, with no creative output. Margaret, 87, still paints every day. Burton gives her the sweetest reward in Big Eyes: the last laugh.