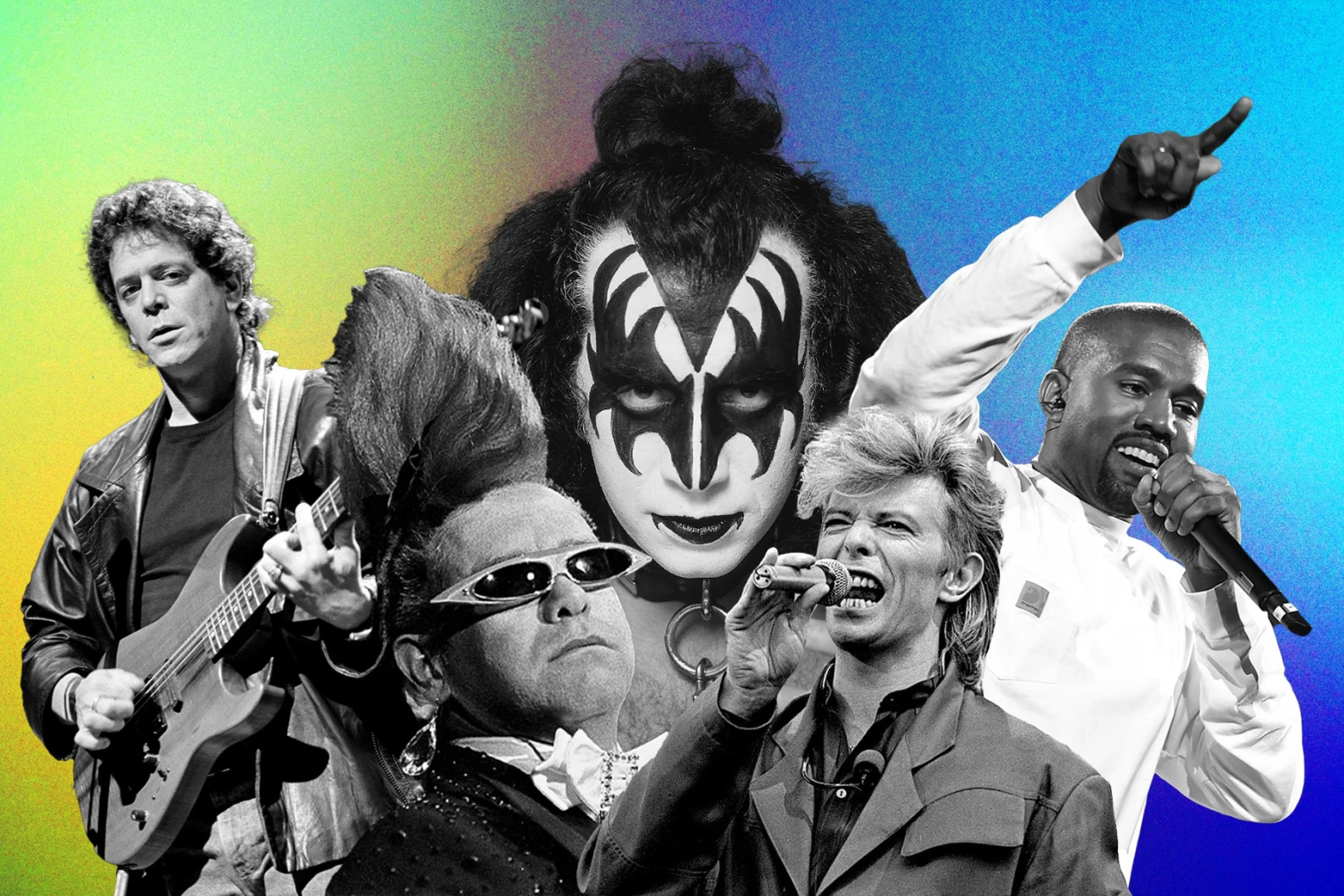

Dylan, Lennon, Bowie, Outkast — even the greatest of greats screw up sometimes. These are the epic duds that diehard fans would like to pretend never happened.

“There is no great genius without a touch of madness.” Greek philosopher Aristotle made this observation roughly 2,300 years ago, long before legit geniuses like Bob Dylan, John Lennon, Carole King, Elton John, Madonna, and Prince proved him right. Among the many celebrated masterpieces these artists have given the world, they have also turned in works so monumentally putrid that nothing short of “a touch of madness” can explain their existence.

Some of these albums were the products of way too much cocaine. (Elton, we’re looking at you.) Some of them came from label pressure to move beyond a cult following by creating commercial music. (Hello, Liz Phair.) Some of them were crafted before a band found its true sound (Pantera, take a bow), while others came long after key members parted and the band had no earthly reason to still exist. (Cough-Genesis-cough).

A huge percent of them were sad victims of horrid Eighties production choices, most notably the dismal period from 1985 to 1988, when cheeseball synths and shotgun-blast snare drums created a sound that has aged worse than a tuna fish and sardine sandwich left in the sun.

Needless to say, rock fans are notorious contrarians and one person’s garbage album is another person’s overlooked classic. We’re sure there are people out there that love Elton John’s Leather Jackets, the Velvet Underground’s Squeeze, and Carol King’s Speeding Time. Some of you will feel that we picked the wrong Elvis movie soundtrack, or that we were insane to leave off Tom Petty’s Let Me Up (I’ve Had Enough) or Public Enemy’s Muse Sick-n-Hour Mess Age. (We happen to enjoy both those records.) There’s also no U2 record because we like them all, even Songs of Experience and October. Those are fighting words to some, and we’re sure many readers will have their problems with this list. True suckiness — like true greatness — is a subjective quality.

Did we rank them? We sure did. Beginning with least-worst and counting down to the most historic flop.

In the early Eighties, Pete Townshend was juggling a solo career, the Who’s difficult post-Keith Moon period, and a pretty nasty heroin addiction. He somehow found the time to cut two stellar solo albums (1980’s Empty Glass and 1982’s All The Best Cowboys Have Chinese Eyes), and the Who’s underrated 1981 LP, Face Dances. But when the time came to enter the studio and cut It’s Hard in 1982, his stockpile of tunes was down to virtually nothing. (It should be noted that throughout this whole time, he saved the best stuff for his solo albums.) Leadoff track “Athena” was a genuine radio hit, and “Eminence Front” is a masterpiece that’s been in the Who’s live repertoire for the past 40 years. The rest of It’s Hard, however, is the absolute low point of the Who’s career. “One Life’s Enough,” “I’ve Known No War,” “Why Did I Fall for That,” and “Cooks County” are clearly the result of exhaustion, very hard drugs, and a contractual obligation to Warner Bros. Records. Townshend himself probably barely remembers making this record, and most Who fans have worked hard to forget it exists.

Billy Joel had nearly a solid decade of success and hits after finally breaking through with The Stranger in 1977, but when it came time to cut 1986’s The Bridge, he was tapped out. “I wasn’t all that focused on writing again and recording again,” he told Rolling Stone in 2013. “I just was a new dad, I just had a baby girl, and I kinda just wanted to be at home with my family at that time, but it was time to get back in the studio.” Working with longtime producer Phil Ramone, he did manage a couple of genuinely great songs like “A Matter of Trust” and his Ray Charles duet “Baby Grand,” but the rest of the album is largely lifeless filler like “Code of Silence” and “Getting Closer.” “I wasn’t that enthusiastic about going back in the studio, and the band that I had worked with for so long had become somewhat disenfranchised from the whole process,” he said. “They really weren’t part of the creative process anymore. It was sort of becoming like a business.”

When original Van Halen singer David Lee Roth left the band in 1985, they simply brought in Sammy Hagar and continued packing arenas, scoring hits, and selling albums by the million. After all, this is a group named after the guitarist and drummer. Why should it matter who is singing? In 1998, they learned the hard way that the singer mattered quite a bit when they brought in Extreme’s Gary Cherone to replace Hagar and cut Van Halen III. This was the dawn of the teen-pop era and Seventies/Eighties rock bands were already aggressively uncool. Still, another song like “Right Now” could still have theoretically landed on the charts. But they didn’t have another “Right Now.” They had songs like “Dirty Water Dog,” “Fire in the Hole,” and “How Many Say I” that left even hardcore Van Halen fans cold. “Cherone has one speed as a singer on III — pained exertion — and longtime bassist Michael Anthony and drummer Alex Van Halen sound as though they’re lumbering at any tempo,” wrote Rolling Stone‘s Greg Kot. “When the band plays it heavy, it mires itself in a Seventies tar pit, with only the chorus of ‘Without You’ achieving any sort of pop resonance.” Cherone left the band soon after the Van Halen III tour wrapped. The next time they toured, Hagar was back in front. It was like Van Halen III never even happened.

The Grateful Dead’s fluke 1987 hit “Touch of Grey” introduced their music to a whole new generation of fans, and moved the band from arenas to football stadiums. It should have been a great time for the band, but Jerry Garcia was deep in the throes of drug addiction and dealing with the aftermath of a five-day diabetic coma in 1986 that nearly ended his life. With Arista thirsty for another “Touch of Grey,” the group began work on another album in early 1989, Built To Last. The cover shows them building an elaborate house of cards on the verge of collapse, which is a nice metaphor for the band at this point. The new Garcia/Robert Hunter compositions like “Foolish Heart” and “Standing on the Moon” leave almost no impact on the listener, and the four songs that feature keyboardist Brent Mydland on lead vocals don’t fare any better. This is the sound of a band worn out from eternal touring and heavily reliant on substances. Myland died of a drug overdose less than a year after Built to Last came out. It was their final record, and it’s noted today largely for the tragic irony of its title.

The soundtrack to Outkast’s Depression-era movie Idlewild generated pretty strong reviews when it came out in 2006, but that’s probably because critics couldn’t even conceive of a subpar album by the Atlanta duo after their incredible streak from 1994’s Southernplayalisticadillacmuzik to 2003’s Speakerboxxx/The Love Below. It’s one of the most impressive runs in the history of hip-hop. But Idlewild is a very different beast, and not just because it incorporates swing, blues, jazz, and soul to keep with the time period of the film. The more time that passes, the clearer it becomes that Idlewild is the product of a creatively exhausted duo who were tired of working together and desperate to go their separate ways. Guests like Snoop Dogg, Macy Gray, Lil Wayne, and Janelle Monáe attempt to lighten things up, but there’s not a single song here in the same universe as “Miss Jackson,” “Rosa Parks,” or “B.O.B.” And even if you forced yourself to like Idlewild back in 2006, when is the last time you put it on? Be honest.

Willie Nelson is a country icon, but over the decades he’s experimented with blues, jazz, folk, and pop standards to various degrees of success. But nothing prepared his fans for 2005’s Countryman, on which he decided to take on reggae. To be fair, he does a decent job with the Jimmy Cliff songs “The Harder They Come” and “Sitting in Limbo.” But the concept totally falls apart on reggae redos of Willie originals like “Darkness on the Face of the Earth” and “How Long Is Forever,” which fall into some horrible middle ground between country and reggae where no artist had ever dared to venture. Toots Hibbert pops up to join him for a cover of Johnny Cash’s “I’m a Worried Man,” but even he can’t salvage this project. “Nelson’s vocals sound like they’re in a different world than these slick, overly tinkered-with instrumental tracks,” Rolling Stone‘s Barry Walters wrote in a two-star review. “Don’t hold your breath for Willie in Dub.”

It’s tempting to say that R.E.M. lost their focus after Bill Berry quit the band in 1996 and they never made another great album, but it’s simply not true. They may have ceased to be a commercial force, but records like Accelerate, Reveal, Collapse Into Now and even Up are stellar albums even if they fail to reach the absurd highs of their earlier works. The only time the group really stumbled was on 2004’s Around the Sun. “The Outsiders,” featuring Q-Tip of A Tribe Called Quest, aims to replicate their KRS-One collaboration from 1991’s Out of Time, but it feels forced. “Final Straw” is a noble, if boring, protest against the Iraq War. The rest of the album simply feels lazy. And if you don’t believe us, listen to the band. “[It] just wasn’t really listenable,” Peter Buck said in 2008, “because it sounds like what it is: a bunch of people that are so bored with the material that they can’t stand it anymore.”

When Metallica were at their absolute low point as a band thanks to James Hetfield’s chronic alcoholism, the defection of bassist Jason Newsted, and uncertainty about where they stood in a post-Napster music universe, they brought in a camera crew to chronicle the making of their LP St. Anger. This led to the stellar documentary Some Kind of Monster, and a deeply disappointing album. Fans rightly fixate on the decision to mic Lars Ulrich’s snare drum so it sounds like he’s banging on a tin can throughout the entire album, but there are deeper issues with St. Anger. The songs are unfocused and seemingly unfinished, and the straight-from-rehab lyrics (“I want my anger to be healthy”) could have used more thought. The band gets very defensive whenever fans or journalists raise these issues, but their set lists tell a different story. They’ve played fewer St. Anger songs in concert than any of their other albums.

The Clash emerged as unlikely pop stars in 1982 thanks to MTV and their hit singles “Rock the Casbah” and “Should I Stay or Should I Go.” But they parted ways with drummer Topper Headon shortly after those songs came out due to his addiction issues, and they fired guitarist Mick Jones about a year later due to personality conflicts. Remaining members Joe Strummer and Paul Simonon decided this presented them with a good opportunity: reboot the band by cutting an album that returned them to their punk roots, though manager Bernie Rhodes insisted they layer in synthesizers and drum machines to sound modern. This resulted in the supremely compromised Cut the Crap, which failed to please New Wave or punk fans. They called it Cut the Crap as a way to disown their recent pop past, but songs like “This Is England” and “Dirty Punk” were pale imitations of better songs from the Jones era of the band. The group split after the conclusion of the Cut the Crap tour.

The sole Genesis album after Phil Collins left the band and was replaced by Scottish newcomer Ray Wilson isn’t a total disaster. “The Dividing Line” is an excellent prog rock tune; “Not About Us” is a beautiful ballad; and “Congo,” “Calling All Stations,” and “Shipwrecked” all have their moments. But then there’s embarrassing dreck like “Small Talk,” “Alien Afternoon,” and “Uncertain Weather” that drags the whole thing into the abyss. Without Collins or original frontman Peter Gabriel at the helm, this was a band without a clear leader or sense of purpose. “Maybe the album could have been better,” Wilson admitted to Rolling Stone in 2022. “We could have had a few more stronger songs on the album had we had a bit more time and work together, maybe. But it is what it is.” When the record bombed, the group fired Wilson and waited around another decade for Collins to return for a nostalgic reunion tour. They never recorded another note of new music.

The Who often get credit with inventing the concept record, but The Kinks Are the Village Green Preservation Society hit shelves six months before Tommy. The Kinks got more ambitious with Arthur (Or the Decline and Fall of the British Empire) in 1969, and their mid-Seventies Preservation concept was so grandiose it took them two separate records across two years. But they hit a wall with 1975’s The Kinks Present a Soap Opera. The record began as a television play about a rock star who trades places with a regular bloke so he can feel what life is like on the other side. It’s packed with distracting spoken-word dialogue and songs that advance the story but do little to stand out on their own. “Musically, there isn’t one really striking melody on the album, although there are plenty of tedious, hackneyed, ready-made ones,” wrote Rolling Stone’s John Mendelsohn in a brutal review. “One might well hear this album as a collection of songs Ray [Davies] left unrecorded over the years because he knew he could do much better. Surely he’s treated every theme represented here infinitely more poignantly elsewhere.”

The Monkees saw their popularity plummet in 1968 when their psychedelic movie, Head, tanked at the box office, their NBC sitcom was canceled, and Peter Tork quit the band. But they soldiered on as a trio and cut two solid albums in 1969, Instant Replay and The Monkees Present, featuring Michael Nesmith-penned country rock gems like “Listen to the Band” and “Good Clean Fun.” When Nesmith quit the band in early 1970, remaining members Davy Jones and Micky Dolenz probably should have called it quits. But they still owed one record to their label. They cut Changes with producer Jeff Barry and reverted back to their earliest days where they merely provided vocals and let others handle everything else. But tunes like “Ticket on a Ferry Ride” and “Acapulco Sun” lack the magic of their early hits. The whole thing just reeks of “contract obligation,” and Jones and Dolenz mercifully ended the group when Changes failed to even dent the albums chart.

Prince was in the middle of a war with Warner Bros. in 1996, and he gave them Chaos and Disorder to fulfill the final terms of his contract. The back of the album features this disclaimer: “Originally intended 4 private use only, this compilation serves as the last original material recorded by (The Symbol) 4 Warner Brothers Records.” The CD booklet features images of a dollar bill rolled up in a syringe and a heart in a toilet. As one can imagine, it’s tough to produce great music when you believe it’s only going to benefit an evil corporation you want to destroy. “Chaos and Disorder is distinguished by its confusion; even the title admits that the album’s fractured parts never resolve into a thematic whole,” Rolling Stone’s Ernest Hardy wrote in a dismissive, two-star review. “At its best, the record sounds like a collection of polished demos. More often, though, it seems like the work of a Prince impersonator.”

Lindsey Buckingham’s decision to quit Fleetwood Mac after the release of 1987’s Tango in the Night was a major blow to the band, but they were able to limp forward, cut 1990’s Behind the Mask, and tour successfully behind it. But things got tricky a couple of years later when Stevie Nicks decided she wanted out too. That was probably the right time to simply put Fleetwood Mac on hiatus, but Mick Fleetwood decided to soldier ahead by bringing in Bekka Bramlett — the 27-year-old daughter of early Seventies duo Delaney and Bonnie Bramlett — to take on the Nicks role. Obviously, this was a hopelessly doomed endeavor. The album from this lineup is 1995’s Time, which does feature a few solid Christine McVie songs like “I Do” and “All Over Again.” But this is Fleetwood Mac in name only, and the material isn’t nearly strong enough to justify its existence.

Kiss didn’t know quite what to do with themselves at the dawn of the MTV era. They were still an enormously popular band, but critics despised them, and many of their fans were moving on to newer acts. In a fairly desperate attempt to establish some credibility, they reunited with producer Bob Ezrin, who’d helmed their best studio album, 1976’s Destroyer, and crafted an elaborate concept record about a dystopian universe where a brave hero named only the Boy who battles evil forces. It seemed like a fairly safe bet since Ezrin had just produced Pink Floyd’s 1979 opus, The Wall, but Kiss are not Pink Floyd. The album got ripped to shreds by the rock press, and their remaining fans just ignored it. The band didn’t even bother touring behind it, and a planned Elder movie never materialized. “That was the one time I would say that Kiss succumbed to the critics,” Gene Simmons later said. “We wanted a critical success. And we lost our minds.”

Pete Townshend’s solo career got off to a very strong start with his under-the-radar 1972 release, Who Came First, and it peaked with 1980’s Empty Glass and 1982’s All the Best Cowboys Have Chinese Eyes. There are even fine moments on 1985’s White City: A Novel. (Spoiler alert: It’s not actually a novel.) But Townshend hit an artistic iceberg and sank with 1993’s Psychoderelict. It’s a concept record about a washed-up Sixties rock star who teams up with a tabloid music reporter to revive his career. There’s actual dialogue from these characters between many of the songs, and little bits of Who classics “Who Are You” and “Baba O’Riley” sprinkled throughout, but it adds up to a boring mess. Worst of all, the songs simply are not there. “English Boy” and “Now and Then” worked onstage when Townshend stripped them down acoustically, but they’re buried under synths on the album. Townshend tried to salvage Psychoderelict by rereleasing it without any of the dialogue, but it was too late. The album was an enormous bomb. It also marked the end of his solo career.

Aerosmith launched an extremely unlikely comeback at the peak of hair metal Eighties, thanks to outside writers and tunes like “Love in an Elevator” and “Rag Doll.” They somehow grew even more popular in the grunge era due to “Cryin,” “Crazy,” “Living on the Edge,” and the appeal of a teenage Alicia Silverstone. But when it came time to cut 1997’s Nine Lives, they were melting down thanks to battles with their manager, infighting, and the temporary defection of drummer Joey Kramer due to grief over his father’s death. They also pushed out Columbia A&R wiz John Kalodner, even though he played a pivotal role in masterminding their comeback. The results were very chaotic sessions overseen by Journey producer Kevin Shirley, and middling ballads like “Hole in My Soul” and “Falling in Love (Is Hard on the Knees)” that felt like pale imitations of earlier hits. They eventually brought Kalodner back to try and salvage the project, but it was too late. The album still sold relatively well, and they followed it up a couple of years later with the Number One hit “I Don’t Want to Miss a Thing,” but Nine Lives has aged terribly. If you doubt us, give “Ain’t That a Bitch” or “Taste of India” a spin.

Devo were just 10 years removed from “Whip It” when they began work on 1990’s Smooth Noodle Maps, but it must have felt like an eternity. Their failure to score another radio hit or find any real traction in the MTV age cost them their contract with Warner Bros. after 1984’s Shout peaked at Number 83, and their move to indie label Enigma did little to revive their fortunes. The group’s 1988 album, Total Devo, didn’t rise any higher than Number 189, and most fans were barely even aware that it existed. They tried one more time with Smooth Noodle Maps, but they were so dejected by this point that they called one of the songs “Devo Has Feelings Too.” The album attempted to infuse Devo’s music with elements of contemporary dance-pop, but it simply didn’t work. For proof, check out their drab take on the Bonnie Dobson folk classic “Morning Dew.” Mark Mothersbaugh was already devoting much of his time to TV and movie projects when Devo cut this record, and it sounds like his mind was clearly somewhere else. The album didn’t even make it onto the album charts, and they wouldn’t attempt another one until 2010.

Liz Phair was put in a very uncomfortable position when indie powerhouse Matador was swallowed up by Capitol in the late Nineties. All of a sudden, the indie singer-songwriter behind revered works like Exile in Guyville and Whip-Smart was on a major label. They didn’t care about critical acclaim. They just wanted hits. Feeling like she had no other choice, Phair brought in the songwriting and production team The Matrix. They’d just worked with Avril Lavigne on her breakthrough hits “Complicated” and “Sk8er Boi” and would go on to work with Britney Spears, Shakira, and Ricky Martin. To put it mildly, this was a less than perfect fit. “It’s sad that an artist as groundbreaking as Phair would be reduced to cheap publicity stunts and hyper-commercialized teen-pop,” Pitchfork wrote in a 0.0 star review so scathing they eventually apologized for it. “But then, this is ‘the album she has always wanted to make’ — one in which all of her quirks and limitations are absorbed into well-tested clichés, and ultimately, one that may as well not even exist.”

Weezer have made quite a few creative missteps ever since they reemerged at the turn of millennium with the Green Album, but at least the shortcomings of albums like OK Human, the Black Album, and Pacific Daydream suffer from the shortcomings of either Weezer alone or outside songwriters that share the Weezer aesthetic. On 2009’s Raditude, they brought in Dr. Luke, Lil Wayne, Jermaine Dupri, and others from far outside the band’s world in a transparent attempt to get back on Top 40 radio. “(If You’re Wondering If I Want You To) I Want You To” — co-written by Butch Walker — gets the album off to a surprisingly decent start, but it collapses once Dr. Luke joins the party for “I’m Your Daddy” and sinks into the abyss when Lil Wayne and Dupri come into the picture for “Can’t Stop Partying.” Being a hardcore Weezer fan involves finding things to hate in almost every album they make, but the band has never given their followers nearly this much ammunition to use against them.

In 1978, the Bee Gees and Peter Frampton learned the hard way with their film version of Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band that a Beatles-themed movie packed with rerecorded Fab Four classics is a very, very bad idea. But just six years later, Paul McCartney thought it could work if an actual Beatle did the singing and acting. He was incorrect. In Give My Regards to Broad Street, McCartney plays a Bizarro Land version of himself trying to track down stolen master tapes for an album. Every once in a while, he gets together with his old pal Ringo, or has a very, very boring dream that never seems to end. The soundtrack features redone versions of “Yesterday,” “Good Day Sunshine,” “Here, There and Everywhere,” and other Beatles tunes. The problem is, nobody was asking for such a thing. You can’t improve on the originals, especially with 1984 production methods. The whole thing is just a woefully misguided mess that has no earthly reason to exist.

Joni Mitchell assembled an impressive lineup of collaborators for her 1985 LP, Dog Eat Dog, including Thomas Dolby, Michael McDonald, Don Henley, Wayne Shorter, Steve Lukather, and James Taylor, but their collective efforts add up to a generic synth-pop LP that does little to distinguish itself. Mitchell takes aim at Ronald Reagan, televangelists, and corporate greed, but the songs are marred by antiseptic Eighties production and her baffling decision to not play any guitar. “It is disappointing that after a three-year silence, her social criticisms are merely the sort of bloodless liberal homilies you would expect from Rush,” Rob Tannenbaum wrote in Rolling Stone. “If Joni wants to reach beyond the faithful who’ll buy this LP to keep their collections complete, why is Dog Eat Dog such an unpleasant listen?”

The 10 years between their 1971 classic At Fillmore East and Brothers of the Road must have felt like an eternity to the Allman Brothers Band, due to the back-to-back deaths of guitarist Duane Allman and bassist Berry Oakley, and the breakup and reunion of the band that followed. They were still in delicate shape by 1981, down a key member thanks to the defection of drummer Jaimoe, and yet somehow Clive Davis thought they were in a position to pump out hit singles for Arista. That explains the glossy sheen on Brothers of the Road and the absence of their signature twin guitar attack. “More than any other LP with the Allman Brothers’ name on it, Brothers of the Road is singles oriented,” Robert Palmer wrote in Rolling Stone. “The group’s trademark two-guitar interplay has been reduced to terse filler on most of the tracks, and there aren’t any of the band’s familiar instrumental raveup numbers either.” In other words, this was a band with an identity crisis trying in vain to adapt to a new musical era. It didn’t work.

Run-DMC are undoubtedly one of the most important groups in rap history, and their four Eighties albums are practically flawless. But the hip-hop world underwent seismic changes in the Nineties thanks to Public Enemy, N.W.A, Jay-Z, and Eminem, and Run-DMC seemed like relics from a distant past, despite records like 1990’s Back From Hell and 1993’s Down With the King, where they did their best to keep up with the trends. In 2001, they decided the only way to win over the TRL audience was to bring Fred Durst, Sugar Ray, Kid Rock, Overland, Fat Joe, Method Man, and Stephan Jenkins into the studio. There’s a guest on nearly every single Crown Royal track, but nobody wanted to hear the Third Eye Blind dude sing with Run-DMC. The album was a colossal bomb, and the group ended tragically the following year when Jam Master Jay was murdered.

Madonna’s output from her 1983 debut LP all the way to 2000’s Music is one of the most impressive runs in the history of pop music. She went through Bowie-like stylistic changes with practically every album but always stayed on top of trends and never lost her ability to generate hits. All of that came to a screeching halt in 2003 with American Life. Released weeks after the start of the Iraq War, the album finds Madonna confronting a post-9/11 world and a desire to move beyond narcissistic desires. “I used to live in a tiny bubble,” she sings on “I’m So Stupid.” “And I wanted to be like all the pretty people that were all around me/But now I know for sure that I was stupid.” These are noble sentiments, but the music came at a time when she was just learning how to play guitar and rap. Her skills at both were rather rudimentary, and her decision to work with French techno producer Mirwais Ahmadzaï (who had been on board for the more successful Music) added yet another element that caused the whole project to become hopelessly muddled when it wasn’t just downright embarrassing. The world in 2003 had little use for Madonna the folk guitarist or Madonna the rapper. When she reverted back to dance music for 2005’s Confessions on a Dance Floor, it was a tacit acknowledgement that she’d made a horrible mistake.

Neil Young has taken on many ambitious projects over the years, but none quite as grandiose as his attempt to rid the world of the internal combustion engine by converting his 1959 Lincoln Continental into a fully electric vehicle, creating a model for car manufacturers all over the globe. It was difficult to get him to talk about anything else at the time, and he made an entire album about the effort with songs like “Fuel Line,” “Off the Road,” and “Hit the Road” that quickly start blurring together. The low point is “Cough Up the Bucks,” where he takes on corporate greed. “It’s all about my car,” he sings. “Cough up the bucks/Cough up the bucks/It’s all about my car/Cough up the bucks/Cough up the bucks.” When he played it during a notoriously long Madison Square Garden concert in 2008 featuring eight songs from the album and one outtake, a handful of people literally fell asleep.

Lil Wayne is a hip-hop genius. But he learned the hard way with 2010’s Rebirth that his skills did not transfer over to the world of rock and roll. He was coming off a long winning streak with three consecutive Tha Carter albums and had been all over Top 40 radio with hits like “Lollipop” and “Got Money.” That didn’t mean, however, that his fans wanted to hear what he’d sound like paired with rock guitars and drums, even if Eminem and Nicki Minaj were along for the ride. “He splutters and wails over tracks stuffed with aggro stomp and bland riffage,” Rolling Stone’s Christian Hoard wrote. “it sounds like he’s been holing up with a bunch of Spymob and Incubus records. Wayne growls like an Auto-Tuned Kid Rock on the swaggering ‘American Star.’ But the hyperclever Wayne we know is missing in action on the anguished chest-thumper ‘Runnin’.’ He stretches his croak past the breaking point on ‘I’ll Die for You,’ like some 21st-century version of Trans-era Neil Young: a vocally challenged genius stuck in limbo.”

Cheap Trick produced some genuinely great albums in the early Eighties, but none of their singles reached the Top 40, and their label Epic’s patience began wearing very thin. In 1986, they brought in producer Tony Platt with the aim of creating a more modern-sounding record. That meant, of course, layers of cheesy synths and electronic drums on every single track. The impulse is understandable since Don Henley, Steve Winwood, Elton John, Rod Stewart, and other Seventies stars were scoring massive hits by utilizing the same formula, but it simply didn’t work for Cheap Trick. They didn’t have a single catchy new song to record, and it’s clear from low points like “The Doctor,” “Rearview Mirror Romance,” and “Kiss Me Red” that their hearts weren’t into this project at all. They almost never touch any of the songs in concert, and the only real reason to play The Doctor today is to hear just how shitty a “modern” record could sound in 1986.

The Doors were still young men when Jim Morrison died in Paris in 1971. They were also deep into a collection of songs they hoped to record with him when he got back to the States. So they finished what they had as a trio and released it as a new Doors album, Other Voices, with Ray Manzarek and Robby Krieger sharing lead-vocal duties. They probably should have called it quits once it became clear the public had no interest in a Morrison-free Doors, but they managed to record one more album, 1972’s Full Circle. It’s an odd mix or R&B, jazz, psychedelia, and rock that never congeals into anything original. There’s also a baffling cover of “Good Rocking Tonight” that they renamed “Good Rockin’.” None of it works. The group made the logical decision to disband shortly after Full Circle came out, and they kept it out of print for several decades. Few fans complained.

Twelve years after Tapestry, Carole King reunited with the production team of Lou Adler, drummer Russ Kunkel, and guitarist Danny Kortchmar for a new album. But instead of crafting another timeless collection of songs, they tried to compete with the New Wave bands of the early Eighties. The album starts with the groan-inducing “Computer Eyes” (“Don’t want to program making love/ I like it real and with feeling”) and only gets worse from there, including a pointless remake of “Crying in the Rain,” a song she wrote for the Everly Brothers two decades earlier. The album didn’t even enter the charts, a first for King, and it would be another six years before she even attempted another one.

The decision to bring Paul Rodgers into Queen made a certain amount of sense back in 2005. Guitarist Brian May and drummer Roger Taylor were in desperate need of a singer, and Rodgers was without a band since Bad Company were on hiatus. Joining forces was a chance to assemble a super-sized stadium show that mixed Queen classics with Rodgers standards like “All Right Now” and “Feel Like Makin’ Love.” “He was his own man,” Taylor said once the partnership came to an end. “He belonged in the blues-soul field, at which there were no better. Our stuff is a little too eclectic, probably.” That’s a polite way of saying that he couldn’t convincingly sing “Bohemian Rhapsody” without the whole thing just seeming ridiculous. But they hadn’t quite come to that conclusion in 2008 when Queen + Paul Rodgers entered the studio to cut The Cosmos Rocks. “Under Rodgers’ command, Cosmos Rocks evokes an unmemorable stretch of drive-time radio, with slow songs like ‘Say It’s Not True’ recalling Air Supply,” wrote Rolling Stone‘s Christian Hoard. “The classic-rock clichés aren’t all Rodgers’ fault: Original band members helped write tracks like ‘Still Burnin’,’ a generic bar-band jam laced with lyrical chestnuts like ‘music makes the world go ’round.’ ” The group parted ways with Rodgers soon after The Cosmos Rocks. They fared far better with Adam Lambert fronting the band, but they’ve yet to record any new music. Maybe they learned their lesson with The Cosmos Rocks.

By the early Eighties, George Harrison was a semi-retired musician whose main interests were car racing and movie producing. But he owed Warner Bros. one last album on his contract before he could devote himself full time to those pursuits. The result was Gone Troppo, a supremely half-assed record driven by synths and light, poppy songs like “Wake Up My Love” and “That’s the Way It Goes” that came and went without most fans even realizing they existed. “So offhand and breezy as to be utterly insubstantial,” Steve Pond wrote in a two-star Rolling Stone review, “the LP is made up of throwaway ditties, instrumental fragments and formulaic love songs.” Harrison spent the next half-decade off the musical grid, but came back strong in 1987 thanks to producer Jeff Lynne, their cover of “I Got My Mind Set on You,” and the formation of the Traveling Wilburys. By that point, Gone Troppo was a forgotten footnote.

It’s not easy to pick Lou Reed’s single worst album considering this is the man who gave us Metal Machine Music, Sally Can’t Dance, and Lulu, but we ultimately went with 1986’s Mistrial. The colossal misfire came after a streak of strong albums in the early 1980s and failed to generate anything resembling a hit. Reed had tried to go for a more commercial sound on his previous album, 1984’s New Sensations, and it had worked pretty well. Mistrial also had a modern sound. This time out, though, the songs he had just plain sucked. Making matters worse, he thought the world was ready to hear him rap on (groan) “The Original Wrapper.” “White against white, black against Jew,” he raps. “It seems like it’s 1942/The baby sits in front of MTV/Watching violent fantasies/While dad guzzles beer with his favorite sport.” Elsewhere on the record, he comes out swinging against violent movies and ends up sounding like a member of the conservative PMRC. “Down the block at some local theater,” he sings. ”They’re grabbing their crotches at the 13th beheading/As the dead rise to live, the live sink to die/The currents are deep and raging inside.” Reed bounced back in 1989 with New York, leaving Mistrial one of the most forgotten albums in his notoriously uneven catalog.

David Bowie hit a major creative cold streak in the immediate aftermath of his 1983 smash, Let’s Dance, spewing out subpar albums like Tonight and the two Tin Machine releases that left even his most hardcore fans extremely underwhelmed. But the clear low point was 1987’s Never Let Me Down. “My nadir was Never Let Me Down,” he said in 1995. “It was such an awful album. I really shouldn’t have even bothered going into the studio to record it. In fact, when I play it, I wonder if I did sometimes.” The record is a showcase of horrid Eighties production choices. Bowie never played a single Never Let Me Down song in concert after the initial tour for it, and he completely reworked “Time Will Crawl” with live drums and modern instrumentation when he assembled the 2008 compilation iSelect. “Oh,” he wrote in the liner notes, “to redo the rest of that album.” Two years after he died, producer Mario McNulty did exactly that for a box set of Bowie’s Eighties work.

Shortly after music manager Tony DeFries parted ways with David Bowie, he came across an Indiana kid named John Mellencamp with dreams of stardom and several years behind him on the bar-band circuit. He renamed him Johnny Cougar, secured a deal with MCA, and produced a record packed with cover songs like “Oh, Pretty Woman” and “Jailhouse Rock.” He also told the press he’d discovered a new Bruce Springsteen. Critics didn’t agree. “Johnny Cougar is a comically inept singer who unfortunately takes himself seriously,“ John Swenson wrote in a brutal Rolling Stone review. “His debut album is full of ridiculous posturing with nothing to back it up … just another ready-made pop throwaway.” The album didn’t even grace the Billboard 200, MCA swiftly dropped him, and he returned back to Indiana thinking he’d blown his one shot at success. Things changed just a couple of years later when he moved to London and scored a hit with “I Need a Lover.”

Michael Jackson had little artistic or commercial use for his brothers in the Eighties, but he felt an obligation to join them for 1984’s underwhelming Victory. He even brought them on the road in 1984 when, by all logic, he should have been playing stadiums as a solo act. When it came time to cut 1989’s 2300 Jackson St., Michael was unwilling to contribute anything more than vocals to the painfully saccharine title track. The rest was handled by his brothers and top-notch collaborators like Diane Warren, Babyface, and Teddy Riley. Despite a few decent moments like “Nothin’ (That Compares 2 U),” nothing here even dented the public consciousness. The Jacksons split up in the aftermath of its failure, only reforming for the occasional oldies gig.

Stephen Stills had good reason to try and revive his solo career in 1984. It had been a very bumpy few years for Crosby, Stills, and Nash, thanks to David Crosby’s addiction issues and legal problems that would soon land the singer in a Texas prison. Despite all that, the Stills-penned CSN tune “Southern Cross” was a genuine hit single in 1982. But he simply didn’t have another “Southern Cross” in his pocket when he entered the studio to cut Right By You. What he had was a collection of subpar songs like “50/50,” “Stranger,” and “No Problem” that couldn’t even be enhanced by guest guitarist Jimmy Page. The low point comes near the end when he tackles Neil Young’s acoustic “Only Love Can Break Your Heart” and layers on synths, drum machines, and a hint of reggae. The end result is almost an act of violence against one of his friend’s most beautiful songs.

Elton John was an absolute train wreck in 1986. He was hopelessly addicted to cocaine, dealing with major vocal problems due to polyps on his vocal cords, and trapped in a loveless marriage to recording engineer Renate Blauel. He was in no condition to record a new album, but he pounded out one a year like clockwork in those days no matter what was happening in his life. This one, however, was his first without a Top 40 single since the early Seventies. That’s because there isn’t one memorable melody or hook on the entire record, and the production is horrid even by the feeble standards of 1986. “Leather Jackets has a lot of awful songs on it, and there’s some very uneven work in the ’80s and ’90s due to the fact that I wasn’t concentrating on what I was doing,” he said in 2001. “And because of the drugs, of course.” He’s called it the worst album in his catalog several times, even though his writing partner Bernie Taupin differs. “I think there’s actually a couple of good songs on there,” he told Rolling Stone in 2013. “I certainly don’t think it’s the low point.” Sorry, Bernie. We’re going to go with Elton on this one.

Van Morrison has always been an eccentric, but he crossed over to right-wing troll territory on 2021’s Latest Record Project, Volume 1. “Morrison’s new record bears a strange resemblance to the unhinged, rambling feel of the pandemic-era internet,” Rolling Stone’s Jonathan Bernstein wrote in a review, “more often than not, its 28 tracks come across as a collection of shitposts, subtweets, and Reddit rants set to knockoff John Lee Hooker grooves.” That is not a typo. There are 28 songs across two discs and 127 interminable minutes, with titles like “Stop Bitchin, Do Something,” “Why Are You on Facebook?”, and “They Own the Media.” (Who exactly is the “they” you’re referring to here, Van?) Sadly, the music is as lazy as his thinking. We’d almost feel bad for the guy if he wasn’t using his art as a way to spread dangerously stupid messages about vaccines. Let’s just hope there’s not a Volume 2 coming at some point. We don’t need to hear Van’s take on Hunter Biden.

The Beach Boys may have been estranged from Brian Wilson when they released Summer in Paradise in 1992, but they did have a renewed sense of purpose thanks to their hit “Kokomo” four years earlier. Mike Love decided they should make an album to serve as the “quintessential soundtrack to summer,” so they mixed redos of old hits like “Surfin’” and “Forever” with covers like Sly and the Family Stone’s “Hot Fun in the Summertime” and the Shangri-Las’ “Remember (Walking in the Sand”). The whole thing is as pointless as it sounds, and it certainly doesn’t get any better when John Stamos pops up to sing the Dennis Wilson parts on “Forever.” Discounting their 1996 country crossover effort Stars and Stripes Vol. 1 — which is the definition of discountable — they wouldn’t even attempt another proper album until 2012’s That’s Why God Made the Radio.

In some ways, it’s easy to have sympathy for the Creedence rhythm section of Doug Clifford and Stu Cook. Watching bandmate John Fogerty write and produce all of their original songs must have been deeply frustrating. In the minds of the public, they became his mere backup musicians even though the group had been slogging it out together since high school. But the sad truth of that matter is that Fogerty is brilliant at writing songs, and they are not. This is painfully evident on the group’s 1972 LP Mardi Gras, where Fogerty agreed to give them a chance at songwriting, singing, and producing. Jon Landau spoke for many critics when he wrote that it was “the worst album I have ever heard from a major rock band.” They broke up not long after it flopped. When Clifford and Cook came back together in 1995 as Creedence Clearwater Revisited, minus their former frontman, they didn’t include a single Mardi Gras song in their stage show. It turns out basing a whole band’s repertoire off Fogerty’s music wasn’t such a bad idea after all.

At the peak of David Crosby’s drug addiction in the early Eighties, Neil Young promised that he’d agree to a new CSNY album if Crosby cleaned up his life. It took a stint in prison for Croz to kick his freebase habit, but Young stuck to his word when he was set free. The problem is that Crosby, Stills, and Nash had been in a songwriting lull for years and didn’t have another set of tunes like “Wooden Ships” or “Teach Your Children” on hand. Young, meanwhile, was saving his best songs for his solo records, and giving them bottom shelf dreck like “This Old House” and “American Dream.” Stills and Young did attempt to revive their Buffalo Springfield-era songwriting partnership on “Got It Made” and “Night Song,” but the Sixties magic was gone. The album was a total dud, and they didn’t even tour behind it. When they finally hit the road in 2000, they didn’t play a single song from American Dream. By that point, it was a half-forgotten footnote to their long saga.

In 1963, Meet the Beatles, The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan, and the first couple of Rolling Stones singles came out. Elvis Presley, meanwhile, was down in Acapulco filming yet another movie, Fun in Acapulco. In this one, Elvis plays a lifeguard (who sings, of course) caught in a rivalry with a fellow lifeguard. By the low standards of Elvis movies, it’s semi-watchable. It was also a hit. The quickie soundtrack is another story. At a time when Elvis needed to up his game to compete with a new generation of rock stars, he was singing “The Bullfighter Was a Lady,” “(There’s) No Room to Rhumba in a Sports Car,” and “You Can’t Say No in Acapulco.” It’s very tough to find a low point of Presley’s recording career since there were so many of them, but many true Elvis aficionados point to this album, and with good reason.

From a strictly historical perspective, Unfinished Music No. 1: Two Virgins is an extremely important album. The 1968 LP marked the beginning of John Lennon’s solo career, and his creative collaboration with Yoko Ono, while offering a window into their private world. The nude image of Lennon and Ono on the cover outraged the religious right, and helped generate a ton of attention for a fledging rock magazine called Rolling Stone when the publication put it on the cover. From a musical perspective, however, Unfinished Music No. 1: Two Virgins is painfully dull and generally pointless. The two 14-minute sides consist of little but inaudible bits of spoken dialogue, tape loops, sound effects, and Ono wailing. There’s almost nothing musical about it, and getting through the full 28 minutes is a brutal slog. Two years later John Lennon/Plastic Ono Band hit shelves. It’s the polar opposite of Unfinished Music No. 1: Two Virgins in every imaginable way. In other words, it’s perfect.

Forbidden is a Black Sabbath record in only the loosest possible sense. Guitarist Tony Iommi was the sole remaining member at this point, and even latter-day members like Ronnie James Dio are nowhere to be seen. The group had essentially been in the wilderness for a decade at this point, and their label convinced them that Ice-T could come into the studio and make the band seem hip and modern again. “It was sold to us that Ice-T was going to be producing,” bassist Neil Murray told Rolling Stone in 2021. “And then it turned out to be his guitar player [Ernie C] from Body Count. I don’t think anybody really thought that he brought any suitable ideas to the production or how the mix wound up. We were mostly pretty disappointed. But it was like, ‘Here you are, journalists and fans, here’s an album you can really tear into it.’ It gave them too much ammunition with how the album sounded. The band wasn’t happy with it, and nobody else was either.” When the album tanked with fans and critics, Iommi had little choice but to reunite the Ozzy Osbourne lineup and pretend like the whole Ice-T thing never even happened.

Dylan aficionados have been arguing for decades about whether or not he reached the nadir of his Eighties creative funk on 1986’s Knocked Out Loaded or 1988’s Down in the Groove. It’s certainly a close call, but Knocked Out Loaded has one certifiable masterpiece: his epic Sam Shepard collaboration “Brownsville Girl.” Down in the Groove, meanwhile, doesn’t have a single redeeming moment. It’s a stiff, lifeless collection of covers (“Rank Strangers to Me,” “Shenandoah”), collaborations with Grateful Dead lyricist Robert Hunter (“Silvio,” “Ugliest Girl in the World”), and originals (“Death Is Not the End,” “Had a Dream About You, Baby”) that are marred by cheesy Eighties drum and synths sounds and an overall feeling of extreme laziness. Eric Clapton, Bob Weir, Jerry Garcia, Mark Knopfler, and the Clash’s Paul Simonon join the festivities, but even their collective star power cannot salvage this disaster. Days after it came out, however, Dylan began his Never Ending Tour. It was a rejuvenating experience that meant we never got an album quite as awful as Down in the Groove ever again, even if he came pretty close with 1990’s Under the Red Sky.

Pantera are undoubtedly one of the greatest metal bands of their era. What a lot of people don’t realize, however, is that they were one of the worst metal bands of an earlier era. If you need to be convinced, check out their 1983 debut, LP Metal Magic, where they sound like a generic, B-list hair band. To be fair, Dimebag Darrell and Vinnie Paul were still teenagers when they made this album, and it was produced by their father, country singer Jerry Abbott. They also hadn’t joined forces with frontman Phil Anselmo. His predecessor, Terry Glaze, is a hopeless Paul Stanley wannabe. This is Pantera in name only, but it still counts as a genuine Pantera album. And it’s absolutely horrid.

By the late Eighties, prog-rockers Yes had split into two feuding versions of the band on the verge of a very expensive court battle. There was the “Owner of a Lonely Heart” Yes featuring drummer Alan White, bassist Chris Squire, keyboardist Tony Kaye, and guitarist Trevor Rabin, and there was the Seventies throwback Yes featuring drummer Bill Bruford, keyboardist Rick Wakeman, guitarist Steve Howe, and singer Jon Anderson. They ultimately realized that a Yes divided against itself cannot stand, and they formed into a singular version of Super Yes and booked an arena tour. They also decided to cut an album. “The problem was that we were three quarters of a way through an album,” Wakeman told Rolling Stone in 2019. “They were three quarters of a way through an album. So the album was given to a guy who shouldn’t even be allowed a food mixer, let alone an album. He did the most dreadful job on the Union album.” Part of that “dreadful job” involved bringing in anonymous studio musicians even though this was a band with two guitarists, two drummers, and two keyboardists. “I called it the Onion album,” Wakeman said, “because it made me cry.”

The Velvet Underground were a band in name only when they released Squeeze in early 1973. The four original members of the hugely influential New York band had left one by one over the previous few years due to internal tension and the group’s failure to have even a tiny bit of commercial success. This was probably a good time to call it quits, but manager Steve Sesnick had the deranged idea they could somehow go forward with bassist Doug Yule — who replaced founding member John Cale in 1968 — taking over as leader. Yule was a real asset when they recorded 1969’s The Velvet Underground and 1970’s Loaded, but on those records, he still had Lou Reed around to write all the songs and sing the vast majority of them. With Reed out of the picture, Yule had to handle everything himself. In his own words, it was like “the blind leading the blind.” Squeeze might have been OK as a Doug Yule solo effort, but as an album by one of the greatest rock groups of all time? Definitely not. It did, however, inspire an upstart U.K. group led by Glenn Tilbrook and Chris Difford to call themselves Squeeze. In many ways, that’s its greatest legacy.

The past five years of Kanye West’s life have been so unbelievably sad and self-destructive, culminating with a horrifying series of interviews in late 2022 where he praised Hitler and defended Nazis, that his recent albums have almost been an afterthought to most people. They are certainly the worst works of his career, and it would be easy to pick Jesus Is King or Donda as the single lowest moment. But we’re going with 2018’s Ye because it marks the beginning of the most disastrous artistic and personal collapse in the history of popular music. Clocking in at a mere 23 minutes, the chaotic, half-baked album was cut in Wyoming right around the time he told TMZ that slavery was a “choice” and started wearing a MAGA hat in public. The uproar over his slavery remark caused him to rework many of the Ye lyrics over a frantic two weeks shortly before the album dropped, which explains screeds like “Just imagine if they caught me on a wild day/Now I’m on 50 blogs gettin’ 50 calls/My wife callin’, screamin’, say, ‘We ’bout to lose it all.’” The Kanye scandals of 2018 seem almost quaint compared to his recent issues, but he’s never made music less vital than this.

From Rolling Stone US.

The Amsterdam-origin festival will take place on Mar. 21, 2026, with Benja, Rooleh and Marlie…

After the global success of ‘Bon Appétit, Your Majesty,’ the rising star is having his…

How Syd Barrett connected Greek mythology, Kenneth Grahame and music, the true modern-day Pan the…

Primary Wave will now take over Spears’ ownership share of her hit songs, including “……

This is not your granddad’s GoT — and thank god(s) for that

Eddie breaks down a powerful new Netflix documentary, Matter of Time, which combines solo concert…