‘You Have Created A Magic Air Through Your Names’: When The Beatles First Met Maharishi Mahesh Yogi

A new book called ‘The Nirvana Express’ by U.K. journalist Mick Brown looks into how the West grew enamored by Indian spirituality and followed a “hippie trail” to India

With the release of “Now and Then” as the “new” Beatles song, fans of the Fab Four have been taken back to an era (about 45 years ago) when spirituality, mind-expanding substances and globe-trotting times were part of Paul McCartney, John Lennon, George Harrison and Ringo Starr’s collective lives.

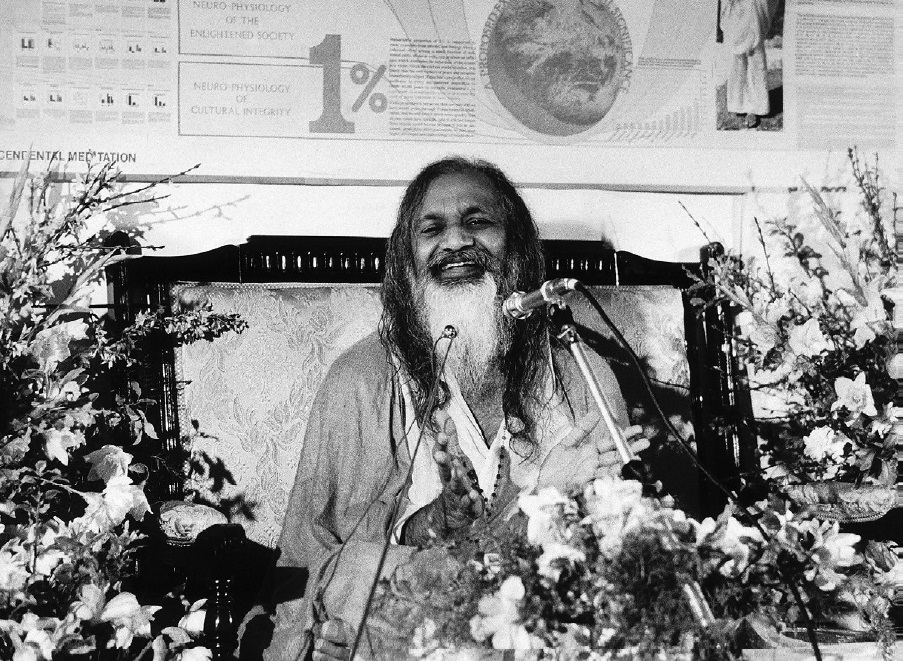

The recently published book The Nirvana Express by U.K. journalist Mick Brown – out via Penguin Random House –reaches into the history of godmen who attracted Westerners across the board – from philanthropists to celebrities to the common man – with wide-ranging Indian religious philosophies. From Swami Vivekanand to Bava Lachman Dass to Maharishi Mahesh Yogi (who called himself the Beatles’ spiritual teacher) all the way down to Rajneesh, Brown details the West’s search for enlightenment.

Below, read an excerpt published with permission from Penguin Random House India from the chapter “Love Is All You Need,” in which Brown details what happened when the Beatles met Maharishi Mahesh Yogi for the first time to learn about transcendental meditation (TM) and how the yogi was keen to further his connection with the band:

John Lennon had initially been sceptical when Pattie Boyd told him about Transcendental Meditation: ‘She said: “They gave me this word but I can’t tell, it’s a secret”, And I said “What kind of scene is this if you keep secrets from your friends?’ But overcoming his reservations, along with George and Paul, and with much the same enthusiasm with which he had adopted LSD, Lennon quickly became a convert.

On 25 August 1967, the day after seeing the Maharishi for the first time at the Hilton Hotel, all four Beatles, along with Pattie Boyd, Jane Asher, Ringo Starr’s wife Maureen, and their friends Mick Jagger and Marianne Faithfull, boarded a train at Euston station in London bound for Bangor in North Wales, where the guru was staging a ten-day ‘Spiritual Guides’ course at a teacher training college.

The encounter came perfumed with the sweet aroma of serendipity, for both the group and the Maharishi. After years of frenetic touring, the exhaustion of being the most popular group in the world, and the dawning realisation that fame and money were not the answer to everything, the Beatles were ready to be beguiled by the promise of bliss, peace and happiness—a high without drugs—to be found by simply meditating for half an hour each day; while the Maharishi, having been apprised of who the Beatles were, was quick to realise just how useful they could be for promoting his mission of global spiritual regeneration.

‘You have created a magic air through your names,’ he told them on their arrival in Wales, ‘You have now got to use that magic influence on the generation that look up to you. You have a big responsibility.’ As the Daily Express reported, ‘The Beatles, all twiddling red flowers, nodded agreement.’

The Bangor retreat would provide an opportunity for the group to be initiated into TM, preparatory to a longer retreat in India planned for the following year. But just two days into the course came the shocking news that the group’s manager, Brian Epstein, had been found dead from a drugs overdose in his mews flat in London.

Over the previous six years Epstein had steered the Beatles’ career, from lunchtime sessions in the scruffy surroundings of the Cavern Club in Liverpool, to becoming the most popular group in the world, as much surrogate elder brother as manager. Without him they were rudderless, bereft. All the Vedic teachings about impermanence had suddenly taken on a horrible reality. But meditation, it seemed, was already offering the soothing balm of consolation and acceptance.

‘There is no such thing as death,’ George Harrison told reporters as the group prepared to return to London, ‘only in the physical sense. We know he’s ok now. He will return because he was striving for happiness and desired bliss so much.’ ‘We all feel very sad,’ Lennon added,

‘These talks on Transcendental Meditation have helped us to stand up to it so much better. You don’t get upset when a young kid becomes a teenager or a teenager becomes an adult or an adult gets old. Well, Brian is just passing into the next phase. His spirit is still with us.’

It was a somewhat different sentiment that Lennon would express some years later when asked about the Maharishi and Epstein’s death: ‘I was stunned, and we all were, I suppose, and the Maharishi, we went in to him, “What?”, you know, “He’s dead,” and all of that. And he was sort of saying, “Oh forget it, be happy,” fuckin’ idiot …’

The Maharishi made no secret of regarding TM as a product to be rolled out to the masses, likening it to ice cream: ‘So having manufactured the ice-cream, and having found a beautiful label and then advertised and accepted its value in the market, now I have to see that every generation receives those beautiful packets in their purity.’

And no amount of money could have bought the promotional fillip that came with the Beatles’ name. In 1965, as part of the programme of spreading TM, a Student International Meditation Society (SIMS) had been established with branches at Harvard, Yale, Berkeley and other colleges across America. With The New York Times hailing the Maharishi as ‘Chief Guru of the Western World’, enrolment in SIMS was growing exponentially. A front-page article in New York’s Village Voice, ‘What’s New in America? Maharishi and Meditation’, suggested that with 2,000 students having signed up to the SIMS course at Berkeley, ‘it now looks that Maharishi may become more popular than the Beatles’ (a neat inversion on the furore that the Beatles had caused a year earlier, when Lennon had opined that the Beatles were bigger than Jesus). Time magazine would later suggest that TM ‘may be the most welcome mystique to attract a youthful following since … the Boy Scout movement’.

The Maharishi himself wasted no time in exploiting his connection with the Beatles, releasing a recording of his lectures on which he billed himself as ‘the Beatles’ spiritual teacher’, and promising the American Broadcasting Corporation that the group would be appearing in a planned television special. Paul and George, along with their aide Peter Brown, were obliged to fly to Sweden where the Maharishi was conducting a course, to gently explain that he was not to use their name in connection with his business affairs. ‘The Maharishi just nodded and giggled again’, Brown wrote later. ‘He’s not a modern man,’ George said forgivingly on the plane home, ‘He just doesn’t understand these things.’

Allen Ginsberg took a beadier view. In December 1967, the Maharishi addressed a gathering of 3,600 people at the Felt Forum in Madison Square Garden, New York. Afterwards, Ginsberg visited him in his suite at the Plaza Hotel, finding the guru surrounded by a group of besuited devotees. Ginsberg taxed him on his views on the escalating war in Vietnam (‘he said [President] Johnson and his secret police had more information and they knew what they were doing. I said they were a buncha dumbells …’) and on the subject of drugs. Had it not been for LSD, Ginsberg told the Maharishi, nobody would have come to see him. ‘Devotees gasped,’ Ginsberg wrote, ‘He said, well LSD has done its thing, now forget it. Just let it drop. He said his meditation was stronger. I said excellent, if it works why not? I said I would be glad to try; can’t do anything but good.’

The Maharishi then appalled Ginsberg by telling him that he had been visited by six hippies in Los Angeles and they had smelled so bad that he had to take them outside into the garden. ‘I said WHAT? You must have been reading the newspapers. He said he didn’t read newspapers … He insisted that hippies smelled. I must say that was tendentious.’

But despite his reservations, Ginsberg concluded that the Maharishi’s ‘Pyramid club’ of people meditating would certainly ‘generate peacefulness’ if it caught on ‘massively and universally’. But ‘his political statements are definitely dim-witted and a bit out of place’.