Charles Manson, the cult leader of the Manson family who masterminded the Tate-LaBianca killings of 1969 and one of the most reviled and fascinating figures in American pop culture, died Sunday night, CBS Los Angeles reports. He was 83. Manson had been rushed to a Bakersfield, California hospital from Corcoran State Prison earlier this month for an undisclosed medical issue.

A career criminal, amateur musician, enigmatic cult leader and unrepentant racist, Manson became synonymous with the dark underbelly and ominous end of the Sixties. The two-day killing spree he orchestrated in August 1969 left seven people dead and, as legend has it, sprang from his mad interpretation of the Beatles’ White Album ”“ specifically the song “Helter Skelter” ”“ which he believed foretold a coming apocalyptic race war.

On August 9th, 1969, tired of waiting for that war to break out, Manson sent four members of his so-called Family to a house on Cielo Drive in Los Angeles with the order to “totally destroy everyone in [it], as gruesome as you can.” They killed the eight-and-a-half-month pregnant actress Sharon Tate, 26, wife of director Roman Polanski; celebrity hairstylist Jay Sebring, 35; screenwriter Voytek Frykowski, 32; heiress to the Folger’s coffee fortune, Abigail Foster, 25; and 18-year-old bystander Steven Earl Parent. The next night, Manson ordered the crew, with one additional member, to a different home on Waverly Drive, where grocery-store-chain owner Leno LaBianca, 44, and his wife, Rosemary, 38, were stabbed to death. At both houses, the culprits left words like “rise,” “piggies” and “helter skelter” scrawled in blood.

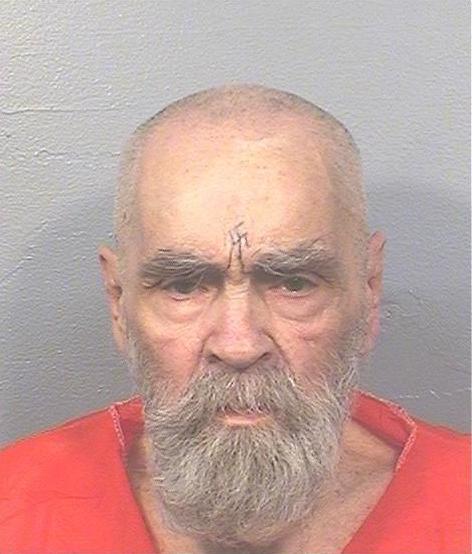

Manson and three other members of his Family ”“ Susan Atkins, Patricia Krenwinkel and Leslie Van Houten ”“ were found guilty of the murders and received death sentences, which were later commuted to life in prison. The trial became a spectacle in and of itself and Manson’s notorious legacy was cemented when he carved an X (later changed to a swastika) onto his forehead in protest of what he saw as unfair treatment by the law. Manson’s absence during the murders and the grip he maintained over his Family underscored one of the case’s most chilling aspects: Atkins, Krenwinkel and Van Houten also carving Xs into their foreheads.

Manson was born in 1934 to a 16-year-old girl in Cincinnati. He never knew his father, and his mother was an alcoholic. He was raised in juvenile halls, reform schools and prisons, ultimately spending approximately 60 of his 82 years incarcerated. Prior to the Tate-LaBianca killings, he was an easy target for cops, bungling burglaries and carjackings, and failing as a pimp. He divorced twice, fathered and abandoned two sons, spent some time studying Scientology and ultimately earned himself a stay in McNeil Island Prison in Washington for forging checks and transferring women across state lines for the purpose of prostitution.

On March 21st, 1967, Manson was released on parole after seven years. He was 32, it was the Summer of Love and he headed to San Francisco. As Rolling Stone wrote in a 2013 profile, Manson “had the mystique of the ex-con, he had a good you-can-be-free metaphysical rap” ”” and he played the guitar. Within months, Manson had corralled several young women into his orbit, starting with the Berkeley librarian Mary Brunner, and soon after 18-year-old Lynette Fromme (later known as “Squeaky”), Ruth Anne Moorhouse, Sandra Good, Krenwinkel and Atkins.

That fall, Manson relocated his growing Family ”“ both Atkins and Brunner would become pregnant ”“ to Los Angeles, in part to chase a dream of rock and roll stardom. During this time, Manson recorded a handful of demos that producer (and one-time Manson Family roommate) Phil Kaufman released in 1970 as Lie: The Love and Terror Cult. Decades later, his songs would be covered by an array of artists including Guns N’ Roses, the Lemonheads, Devendra Banhart, Brian Jonestown Massacre and Rob Zombie, but at the time he was unable to score a record deal.

Nevertheless, Manson managed to infiltrate the late Sixties Los Angeles music scene through a haphazard connection to the Beach Boys after Dennis Wilson picked up several Family members hitchhiking on Sunset Strip. Manson and the girls eventually moved in with Wilson where they mingled with other members of the Los Angeles scene, like producer and Beach Boys associate Terry Melcher. While Manson was never able to impress Beach Boys mastermind Brian Wilson, the group did record one of his songs, “Cease to Exist,” which they reworked heavily, renamed “Never Learn Not to Love” and released on their 1969 album, 20/20, and as the B-side to “Bluebirds Over the Mountain.” Manson did not get a writing credit.

In an extensive 1970 interview with Rolling Stone, Manson spoke with David Felton and David Dalton about his music career (their notes from the interview are in italics). “I never really dug recording, you know, all those things pointing at you,” Manson said. “Greg would say. ‘Come down to the studio, and we’ll tape some things,’ so I went. You get into the studio, you know, and it’s hard to sing into microphones. [He clutches his pencil rigidly, like a mike.] Giant phallic symbols pointing at you. All my latent tendencies ”¦ [He starts laughing and making sucking sounds. He is actually blowing the pencil!] My relationship to music is completely subliminal, it just flows through me.”

In March 1969, after failing to get a record deal with the Beach Boys’ label, Brother Records, Manson decided to take his anger out on Terry Melcher. He went to the producer’s house on Cielo Drive, but discovered Melcher had moved out. Instead, new resident Sharon Tate was throwing a party.

In July of that same year, Manson and his Family perpetrated two other murders. First, they killed a drug dealer named Bernard “Lotsapoppa” Crowe, whom Manson associate Tex Watson burned in a deal. Not long after, Manson joined his friend Bobby Beausoleil as he sought revenge on Gary Hinman, a member of the Straight Satans biker gang, over another bad drug deal. Several weeks later, Manson ordered the Tate and LaBianca murders.

For months, the Los Angeles Police Department treated the two killings as unrelated. In October, 27 people were arrested at the Manson Family’s home base, Spahn Ranch, for car theft, but it wasn’t until a month later that authorities got their first big break when Susan Atkins bragged to fellow inmates about the murders.

Even after his conviction and sentence, Manson remained a prominent figure in American pop culture. Los Angeles deputy district attorney Vincent Bugliosi chronicled the case in his 1974 book Helter Skelter, which became the biggest selling true-crime book of all time. A year later, Manson acolyte Squeaky Fromme attempted, and failed, to assassinate President Gerald Ford. Meanwhile, Manson maintained a high profile from prison, granting interviews throughout the Eighties and Nineties. During one infamous chat with Diane Sawyer, he roared, “I’m a gangster, woman. I take money!”

When Hedegaard visited Manson in prison in 2013, he painted a picture of an old man with gray hair, bad hearing and bad lungs who walked with a cane. Throughout the interview, Manson maintained his innocence, saying he never killed anyone nor gave orders to kill anyone. He also denied the Helter Skelter race-war theory presented in Bugliosi’s book (“Man, that doesn’t even make insane sense!”) and downplayed the idea that he was any sort of leader: “Go for what you know, baby; we’re all free here. I’m nobody’s boss!”

Yet Manson was also frequently joined by a new companion, Star (real name Afton Elaine Burton), a young woman who moved to Corcoran, California for Manson, drawn by his stances on environmental issues. In 2015, Manson and Star were granted a marriage license, but it expired before they could marry. Nevertheless, Star devoted several years caring for Manson and attempting to rehabilitate his public image. She too carved an X onto her forehead.

In January, Manson was taken from Corcoran State Prison, where he was serving a life sentence, to a nearby hospital in California’s Central Valley for an undisclosed medical issue, per the Los Angeles Times. According to a source, Manson was seriously ill, but could not provide details. Officials from the Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation declined comment, saying inmates’ medical information must remain private.

Manson spent the majority of his life behind bars, but even he seemed to recognize it was where he belonged. In 1970, he told Rolling Stone, “Being in jail protected me in a way from society. I was inside, so I couldn’t take part, play the games that society expects you to play.” He even espoused his love of solitary confinement: “I began to hear music inside my head. I had concerts inside my cell. When the time came for my release, I didn’t want to go. Yeah, man, solitary was beautiful.”

Over forty years later, his opinion had not changed. During his interview with Hedegaard, he reiterated his love of prison, as well as his false claim that the Beach Boys’ song “In My Room” was based on his own tune, “In My Cell.” “Like all my songs, it’s about how my heaven is right here on Earth,” Manson said. “See, my best friend is in that cell. I’m in there. I like it.”