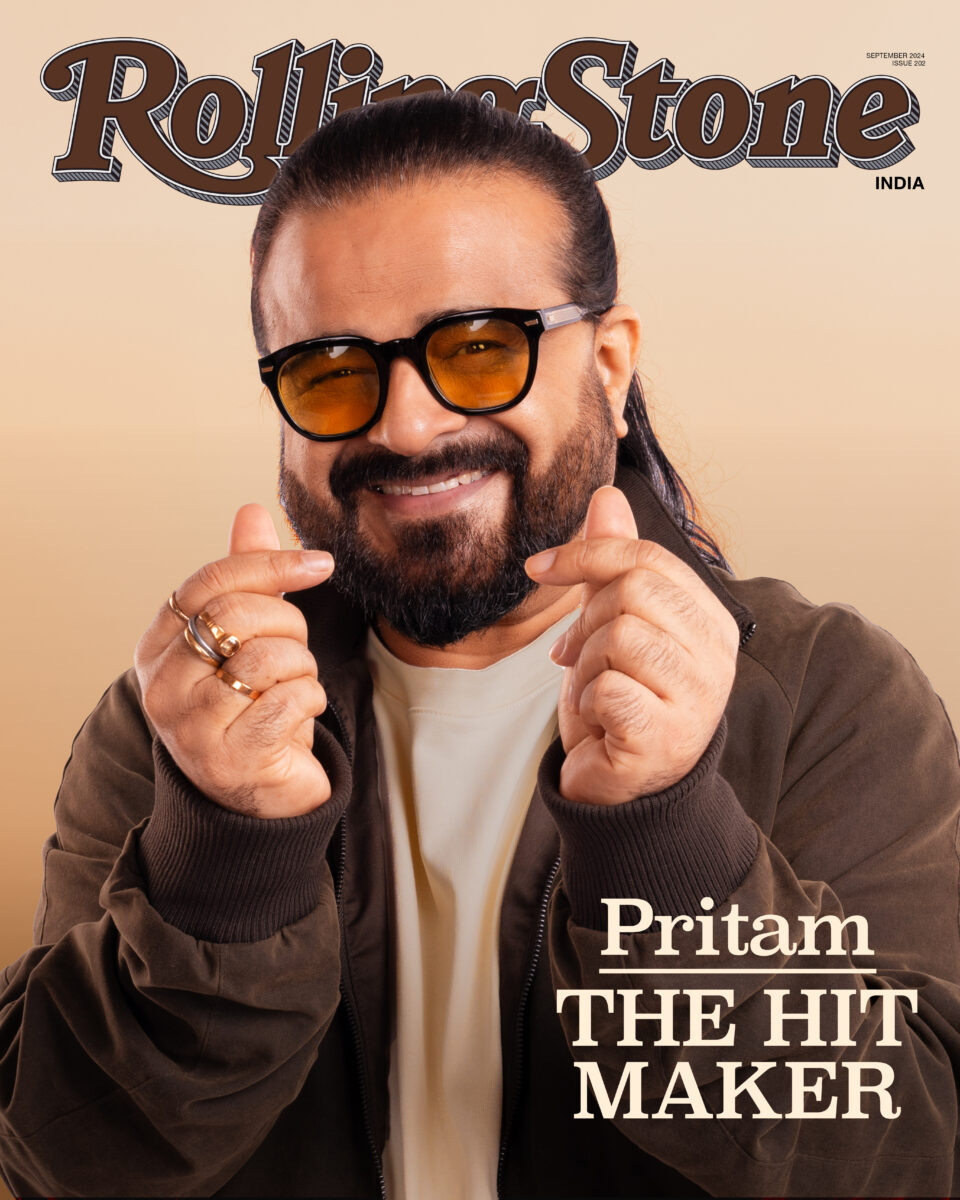

Pritam: The Hit Maker

Inside the mind of Hindi film music director Pritam Chakraborty, who recently won his first National award for Brahmastra: Part One – Shiva, on how he creates scores that endure and songs that clock millions of streams

It’s close to midnight when Pritam Chakraborty heads back to Mumbai from Delhi NCR. Over a phone call, the Hindi film music composer sounds animated, buzzed from a concert rush. He has just wrapped up a stage performance to a packed audience, alongside Norwegian electronic artist, Alan Walker, to mark the release of his new collaborative track, “Children Of The Sun”. “It’s only been three days since the track released, but the response has been terrific,” says 53-year-old Chakraborty with child-like enthusiasm of the song, which also features Hindi playback singer Vishal Mishra.

“Children Of The Sun” encapsulates everything that the global music scene seems to be hooked onto right now – Punjabi pop, glistening synth spins and party-starting drops. The track lists eight composers on its credits and three lyricists including Chakraborty, Walker and Norwegian composer Gunnar Greve, who was key to kickstarting the collaboration back in 2019. “The great thing about Alan’s music and Scandinavian music in general is that it’s very melodic. While so many of us worked on it and never even met each other – it was all done online – it has the same soul,” says Chakraborty. “Children Of The Sun” indeed sounds like it could have fit right into the soundtrack of Rocky Aur Rani Kii Prem Kahaani or Brahmastra: Part One – Shiva, which snagged Chakraborty his first ever National award in August.

To Chakraborty, the award is an ephemeral pleasure. “But it is very important to my mom. She has mentioned it a few times. She’s 88…,” adds the composer. Recognition for Brahmastra, this year, also came in the form of over 500 million streams for “Kesariya,” the first Indian track to have achieved this record on Spotify. Rendered by yet another hit maker, Arijit Singh, “Kesariya” was loved and hated in equal measure when it released in 2022, but engulfed every platform that played music. Chakraborty worked on the song for four years. “The version of “Kesariya” that you now hear happened here in the studio at home. The first ‘Kesariya’ happened in Benares in 2018,” said Chakraborty, when we met him ahead of the film’s release in 2022, on a sleepy Sunday afternoon at his suburban Mumbai residence, which also includes his studio. “It was a full on dance number, which was also shot like that. Later, when Ayan (filmmaker Ayan Mukherjee) fit it into the movie, he felt it wasn’t working. From a thumping dance song, I turned “Kesariya” around into a slow love song.”

Lyricist Amitabh Bhattacharya, who has worked with Chakraborty in over 20 films, including Brahmastra, says that the composer’s biggest strength lies in staying relevant. “He really challenges you as a composer by constantly changing things around so that the music is in tune with the sound that is prevalent now. I used to crib about it to him initially, but it made me understand how sound palettes change,” says Bhattacharya, referring to songs such as “Kalank,” the title track of the 2019 film by the same name, for which the composer created five versions of the song.

Creating different versions of a track is part of Chakraborty’s creative process. “I can actually release an album full of reprises for Laal Singh Chaddha (starring Aamir Khan),” says Chakraborty.

The musician adds that he is constantly tweaking songs “to beat boredom” and because it challenges him as an artist. “To make a new song, I have to make 15-20 songs. Out of that, two or three come out good and I play those to the director,” he says. There are times when a song meant for one film finds its way into another. Chakraborty remembers working on the scores for the Shah Rukh Khan-starrer Billu Barber and the Ranbir-Katrina film Ajab Prem Ki Ghazab Kahani one after the other in 2009. “I made ‘Kaise Bataaye’ (Tu Jaane Na) for Billu and SRK said that he liked the song, but didn’t fit the situation. When Ajab came up, I knew it was perfect,” he says.

Unlike Himesh Reshammiya, who finds it easy to work on multiple films because he has a database of songs handy, Chakraborty is not taken in by the idea of creating a music bank. “I have to cater to a film and its script. What works for Brahmastra will not work for Laal Singh Chaddha — the films are poles apart. But when I know that some songs are good and don’t work for the film they were made for, they stick in my head. I keep humming them and the music comes back in another song. Har gaane ka apna luck hota hai,” he says.

If a director likes a song, however, Chakraborty lets it be. Filmmakers such as Karan Johar, says Chakraborty, know exactly what they want. “Karan’s clarity is on some other level. If he likes it, he likes it instantly. His instincts are strong. He picked three of the five songs – “Channa Mereya,” “Bulleya” and “Alizeh” during the first sitting for Ae Dil Hai Mushkil,” he says.

Johar favorites – music director trio Shankar-Ehsaan-Loy – brought their signature mix of jazz-blues and Hindustani classical-led rock to blockbusters such as Kabhi Alvida Naa Kehna and Kal Ho Naa Ho. Vishal-Shekhar, whom Johar zeroed in for their fresh take on hits such as “Disco Deewane” for Student Of The Year, have delivered raging party hits such as “Ishq Wala Love” in the same film. And it’s Chakraborty’s guitar-driven ballads and folk sensibility, drawing from Punjabi as well as Bengali folk music sounds, which closed the distance between soulful pop and classic songcraft for Johar in his recent releases such as Rocky Aur Rani Kii Prem Kahaani.

Chakraborty is known to work manic schedules to finish scoring, composing through the night and early morning, breaking to catch up on his sleep until late afternoon. He no longer signs on “20 films a year” as was the case a decade ago. “When there’s too much work, the music does suffer. It takes a toll. I want to spend more time on a song, and I don’t get that chance. Every song needs a lot of nurturing after it is composed until the mixing stage,” says Chakraborty. Academy award-winning sound designer Resul Pookutty, who was Chakraborty’s senior by a year at FTII is all praise for the composer: “Pritam Chakraborty is a phenomenally talented music director. He could have been another SD Burman, but we haven’t explored him. The burden of commercial music has fallen on him.”

The payoff for the hectic pace at which he has been working all these years lines a wall in his home studio – trophies that mark his career highs. So, it’s surprising when Chakraborty says: “I don’t like anything I do. It’s tough to be your biggest critic because you tend to lose perspective and that happens a lot because when you’re working on a song, you hear it so many times.” The first version of the track then acts as his sonic compass.

There have been massive low points in his career too. Chakraborty rues that news of lifting music has always been a sore point in his musical journey. As soon as “Kesariya” released, there was talk of the song being plagiarized. “Kesariya” was compared to Pakistani band Call’s track “Laree Chootee” and a Punjabi folk song titled “Charkha.” “I already have baggage that I carry around from my past. The minor similarity is just accidental. When someone from my team of assistants or anyone on the film crew says that a song sounds similar to something else that they’ve heard, I immediately change it,” says Chakraborty. Generic chord progressions can often lead to common melodic progressions, he explains. “Two melodies of a similar generic chord progressions can overlap at places. To common untrained ears, these sound the same. Only the first four notes (of “Kesariya”) match and after that, the melodies have their own journey. It is definitely not copied,” says the composer.

During his early years as a composer, Chakraborty was pulled up for plagiarism in soundtracks of films such as Dhoom (2004), Chocolate (2005), Garam Masala (2005) and Ek Khiladi Ek Haseena (2006) and Gangster (2006) among others. He publicly admitted to having made mistakes and also not crediting composers whose works he had used in films because he believed that the producers would acquire the rights to use the original music.

The tide turned in 2012 when Iranian pop group Barobax, who filed a plagiarism case against the composer, withdrew the case. The band had claimed that their song “Soonsan Khanoom” was copied by Chakraborty for the track “Pungi,” which featured in the Saif Ali Khan film Agent Vinod.“ The allegations that are coming up now (during “Kesariya”) are really stupid. It’s very strange that neither my assistants found any similarity nor even Ayan’s assistants noticed it when the song was being shot,” says the composer.

But since the release of movies like Life In A Metro (2007), the composer has however created a soundscape that is his own. “I like rock, so I add an element of soft ballad rock to everything I make. One of my strongest influences is folk because I used to sing Bhatiali and Bhawaiya folk songs as a kid.” His roots in Kolkata remain strong. After all, he has spent half his lifetime in the city. “All my childhood memories are attached to Calcutta. Every time I visit, I can hear the Pather Panchali flute playing in the background as soon as I enter Calcutta. Do you remember the scene where Apu comes back from Benares to Bengal? As he enters Bengal, the theme plays in the background, it’s like that every time I go to Calcutta,” says Chakraborty, who lived in Entally in Central Kolkata during his growing up years.

A career in music seemed like an unlikely choice even though he was surrounded by it. “My father worked in the Indian Railways, but ran a music school at home as a part-time thing. We lived in a one-room home with a partition. I would sit with my books on one side and there would be music playing on the other. My father’s friends would drop by and play folk, Baul and what not,” says Chakraborty, recalling how his father, Prabodh, played all kinds of music including Rabindra Sangeet on the Hawaiian steel guitar.

All through school and college, Chakraborty played in bands. “I’ve played in rock ’n roll bands to Kishore Kumar bands to Mukesh (cover) bands. My vocal range was such that I would do the male and female voice for some of the songs,” says the composer, cracking up at the memory. Chakraborty even played with iconic Bengali rock band, Chandrabindoo, during his college days. “I played bass early on for the band,” he says.

While at Presidency, he graduated with a degree in geology. “Some people said that I could travel a lot if I took up geology,” says Chakraborty, who realized much to his disappointment that this meant traveling to “godforsaken places in the heat” to make geological field reports on sand and mineral deposits. After a year of pursuing a Masters in geology, while prepping to crack the Union Public Service Commission (UPSC) exams to land a job in the civil services, Chakraborty came across an ad in a UPSC textbook that changed his life’s trajectory. The country’s premier film school, Film and Television Institute of India (FTII) had advertised for admissions into a course in Sound Recording and Engineering. Chakraborty secured admission at FTII and moved to Pune in 1993. “Coming from an extremely lower middle-class family in Calcutta, going to Bombay to settle there and make music was a faraway dream. But at FTII, everybody is eating, drinking and breathing films and another universe opened up,” says Chakraborty, who understood the nuances of scoring for cinema at the institute, pointing to faculty member, Kedar Awasthi, as a key influence.

After moving to Mumbai in 1997, he was sought out by FTII alumni. “Raju Hirani used to give me a lot of work. I’ve done so many of his ads and TV serial titles,” says Chakraborty, who did his first film, Dunki, with Hirani in 2023. Hirani also introduced Chakraborty to filmmaker Sanjay Gadhvi, who gave him one of his biggest hits in Dhoom (2004). Filmmaker Anurag Basu is another longtime collaborator, having worked with Chakraborty on films such as Life In A Metro, Barfi!, Jagga Jasoos and Ludo. “We’ve been working together since the 90s. I think he has a great understanding of cinema. He’s a cinema lover. When you compare Ae Dil Hai Mushkil or Dangal or Barfi!, you can’t tell that the music has been done by the same person. He doesn’t force his signature on the film’s music. More than a music director, he’s become my bouncing board for ideas,” says Basu.

Today, working is also Chakraborty’s means to re-establishing ties with old friends. “The sole purpose of doing Freddy (starring Kartik Aaryan) is that I get to meet Jayu, the producer (Jayesh Sewakrawani). He’s an old friend and like with a lot of old friends, I had lost touch with him. A lot of times, I’m working with my friends – that’s my only kind of break and pastime,” he says.

When he hits a creative block or just wants to get away, Chakraborty often escapes to Khandala or Lonavala. “I have fun getting out of the studio to make music. I go to Khandala to compose sometimes. Where else can you hear cicadas accompanying your music?” he asks. While working on the score of Laal Singh Chaddha, Chakraborty made several trips to Aamir Khan’s Panchgani home to compose. “We cracked ‘Kahani’ on the first day and ‘Main Ki Karaan?’ happened on the second day in Panchgani. We stayed there for four to five days and finished three songs,” recounts Chakraborty.

For the soundtrack of the 2007 Kareena-Shahid starrer Jab We Met, filmmaker Imtiaz Ali wanted to dash off to Khandala for a composing session and found out that Chakraborty was otherwise indisposed. “Imtiaz wanted me to finish “Nagada Nagada.” He wanted us to leave for Khandala right away and asked me what I was up to. I told him that I was getting married,” remembers Chakraborty, who left for the hill station the day after his wedding and composed the song in half a day.

When he does get a real break, he spends time with his son Purvash, 16 and Mrignaini, 14. “I have missed their growing years and that’s a huge guilt that I have. Now they’ve grown up and they don’t need you. Friends have become more important than anyone else,” he says. On another big break, he also managed to fulfill his mother’s longtime wish to visit Paris and London last year.

With two big releases – Metro In Dino, starring Anupam Kher and Sara Ali Khan and War 2 , starring Hrithik Roshan and Kiara Advani – lined up, Chakraborty might have to settle for Khandala breaks. Unless, of course, Alan Walker ropes him into an international tour.

Lalitha Suhasini is the former editor of Rolling Stone India and currently teaches journalism at FLAME University.