Friend Of The Devil: Remembering Jerry Garcia

Next year will mark 25 years since the death of the legendary singer and his iconic band Grateful Dead. The author recalls gate-crashing one of their last concerts as a teenager

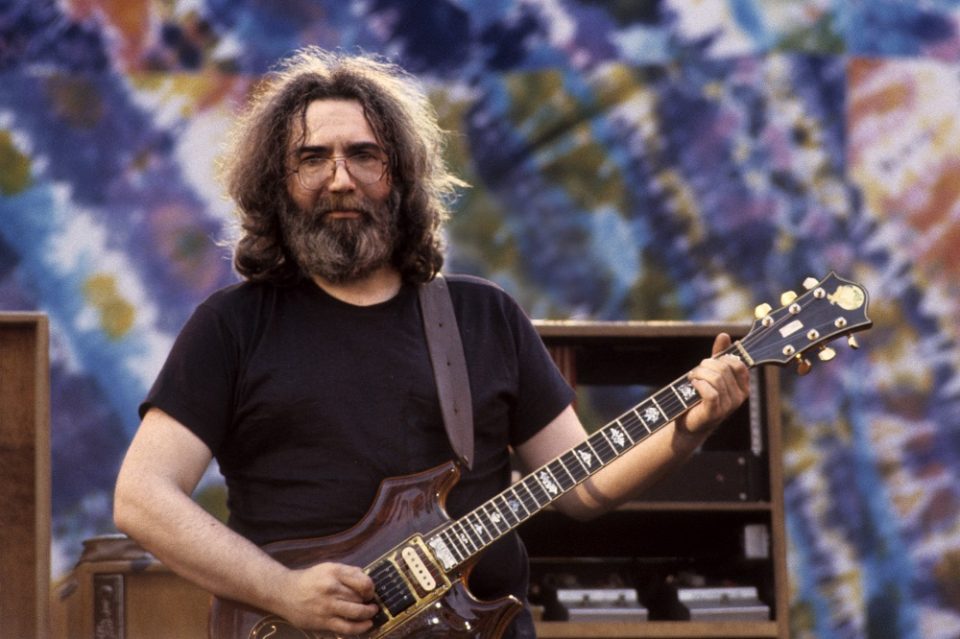

Jerry Garcia performing with the Grateful Dead at the Greek Theater in Berkeley on May 22nd, 1982. Photo: Clayton Call/Redferns/Getty Images

Jerry Garcia was dying. There had been whispers on the grapevine for years, but it was now confirmed. The singer-songwriter and guitarist was a demi-god to legions of devoted Deadheads. And like many humans who are elevated to near mythical status, Garcia’s demons were always in close proximity, reminding him that time was running out.

His heroin and cocaine habit saw him in and out of rehab for decades, and severe diabetes had led to a coma in 1986 that nearly cost him his life. In his final years, he lost sensation in his fingers due to clogged arteries was increasingly disoriented during performances, often missing notes and chords.

The band was slated to perform in a couple of weeks at the Giants stadium in New Jersey. It was perhaps our last opportunity to see them live, but unfortunately, tickets were all sold out. At the ripe old age of nineteen, such things are seldom a deterrent. So we did what was expected of bona fide Deadheads, we gatecrashed the show.

Takashi, Jamal, Bill and I were freshmen at a mid-sized liberal arts school in New England. We were part of a four-person band and shared a house near campus. Our signature sound, which could be loosely described as ‘East coast hippie jazz,’ was influenced by the likes of Miles Davis, Weather Report, Phish, Bela Fleck, and of course, the Grateful Dead. We were an eclectic bunch. Takashi, originally from Tokyo, played keyboards, I played bass guitar, Jamal, our lead vocalist from Istanbul, doubled up on rhythm guitars while Bill, a Boston native, played drums.

Garcia (right) and Carlos Santana (left) with promoter Bill Graham pose for a portrait in 1976 in Mill Valley, California. Photo: Richard Creamer/Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images

We loaded our instruments in the capacious trunk of Takashi’s vintage Cadillac sedan and hit the road at dawn, reaching the venue before sunset. We quickly found a spot on ‘shakedown street’ (named after their 1978 album), the section of the parking area where deadheads traditionally gathered to scalp tickets, as well as to sell food, clothing, handmade jewellery, alcoholic beverages, pot edibles, LSD and mushrooms. It was a convenient way for the faithful to fund their travels and allowed them to live on the road for months and years on end.

Like many iconic groups, the Dead started their career playing at dive bars, parlors and house events. Their original backer was the sound engineer Owsley Stanley aka the ‘Acid king’ who manufactured and supplied most of the LSD in the Bay Area. He put up the band in a rented house and paid for their sound equipment.

One of the group’s earliest major performances – the ‘Mantra-Rock dance’ – was organized by the San Francisco Hare Krishna temple and took place on Jan 29th, 1967, at the Avalon ballroom. Accompanying the band on stage was the Hare Krishna founder Bhaktivedanta Swami, beat poet Allen Ginsberg and singer Janis Joplin. Proceeds from the concert were donated to the temple and soon after the band released their first LP, The Grateful Dead, on Warner Brothers. The album cover featured an image of Yoga-Narasimha, the man-lion avatar of the Hindu god Vishnu.

The core team was already in place by then – Bob Weir on rhythm guitar and vocals, Phil Lesh on bass, Ron ‘Pigpen’ McKiernan on vocals and harmonica, Mickey Hart and Bill Kreutzmann on drums, and of course Jerry Garcia as the lead singer and guitarist. With the exception of Ron McKiernan who died of liver cirrhosis at 27, the rest of the band remained together till the end, joined by Keith and Donna Godchaux on keyboards and vocals respectively. Later, the multi-talented Brent Mydland replaced Keith, penning the lyrics to classics such as “Hell In a Bucket” until an accidental drug overdose took his life in 1990 at 37.

Garcia (left), Donna Godchaux and Bob Weir perform with The Grateful Dead at Santa Barbara Stadium on June 4th, 1978 at U.C Santa Barbara. Photo: Ed Perlstein/Redferns/Getty Images

Robert Hunter, the band’s primary lyricist (along with John Perry Barlow who worked separately with Bob Weir), played a central role in creating the Grateful Dead mythology. He collaborated with Jerry on classics such as “Scarlet Begonias,” “Ripple,” “Dark Star,” “Friend of the Devil,” “Truckin’,” “Franklin’s Tower,” “Sugar Magnolia” and “Terrapin Station.” (Hunter has also published translations of Rainer Maria Rilke’s Duino Elegies and the Sonnets to Orpheus and several volumes of his own poetry).

The first lyrics that he wrote for the Dead were composed while on LSD. The words were later set to music and became known as “China Cat Sunflower.” The man had the uncanny ability to articulate the synaesthetic visions induced by LSD:

Look for a while at the china cat sunflower

Proud walking jingle in the midnight sun

Copperdome bodhi drip a silver kimono

Like a crazy quilt star gown through a dream night wind

That, along with Jerry’s long, improvised guitar solos and his knack of never playing a song the same way twice, burnished their reputation as the undisputed kings of psychedelic rock.

The genius of the Grateful Dead was that they could be deeply subversive – upending tropes about the ‘American Dream’ – without being overtly political. Take for example these lines from “Ship of Fools”:

Went to see the captain, strangest I could find,

Laid my proposition down, laid it on the line.

I won’t slave for beggar’s pay, likewise gold and jewels,

But I would slave to learn the way to sink your ship of fools.

Despite their hippie flower-power image, much of the Dead’s music was about rogues and rascals, outlaws on the run, drinking, gambling, brawls, illegitimate offspring and freight trains – sometimes all in the same song. The lone wolf-wounded outlaw with an existential edge was a hat tip to Johnny Cash, Willie Nelson and Waylon Jennings.

“Friend of the Devil,” a Dead classic, from the album American Beauty (1970), is about a cuckolded bigamist fleeing from a sheriff’s posse and a pack of hounds, bargaining for his life with Lucifer. Hunter’s charming anti-hero is a poetic conman with friends in dark places. “Mississippi Half-Step Uptown Toodeloo” (1976) is about a cheating gambler fleeing from his debtors while “Morning Dew” (1967) is a folk song about the two lone survivors of a nuclear apocalypse.

“Truckin’,” also from American Beauty, was written after the police raided their hotel and arrested 19 people with possession of various narcotic substances:

Sittin’ and starin’ out of the hotel window.

Got a tip they’re gonna kick the door in again.

I’d like to get some sleep before I travel.

But if you got a warrant, I guess you’re gonna come in.

All charges were later dismissed except those against sound engineer Owsley, who was already facing charges for mass-producing LSD in his lab.

The band encompassed a wide range of styles over the course of their 30-year career, seguing from progressive garage to psychedelic jam suites, alt-Americana, space-jazz, and hippie disco before settling into the weighty, mature rock ballads of their later years.

The Grateful Dead. Photo: Mick Hutson/Redferns

On June 17th, 1991, as the sun dipped below the horizon, the four of us gatecrashed the show along with a hundred other ticketless vagabonds. We clambered up the tall wire fence like monkeys, dropped to the other side and ran into the amphitheater. The few security guards on location half-heartedly tried to shoo us away, but soon disappeared, having seen this routine play out hundreds of times.

Stretched out before us was a swaying, kaleidoscopic sea of humanity. Deadheads with tattoos, dreadlocks, beads, bandanas and tie-dye tees filled the massive stadium. The air was thick with the sweet, pungent fumes from countless marijuana cigarettes.

As Bob Weir strummed the opening chords for “Eyes of the World,” the audience erupted in ecstatic frenzy. And when Jerry began singing, the crowd went completely silent, each one transported into his or her own private universe. “Eyes of the World,” released in 1990, is one of the most spiritual songs in the Dead catalog, evoking profound images of creation, dissolution, oneness and eternity.

There comes a redeemer, and he slowly too fades away

And there follows his wagon behind him that’s loaded with clay

And the seeds that were silent all burst into bloom, and decay

And night comes so quiet, it’s close on the heels of the day

I first came across the music of the Dead on a “bootleg” tape loaned to me by a friend. Bootlegs were unofficial recordings of the band’s live performances by fans, used as currency in a flourishing extralegal economy, and traded for psychedelics, food and tickets. Dead bootlegs could only be traded on the underground. They could not be bought or sold for cash.

The man who would later become the band’s official archivist, Dick Latvala, started his bootlegging career while still employed as a zookeeper in Hawaii, shipping bundles of weed through the US Mail in exchange for music. He went on to curate the popular series of official releases of live shows called Dick’s Picks.

At the time of his death in August 1995, Jerry Garcia was the most recorded guitarist in history. By some estimates, more than 2,200 Grateful Dead concerts, and 1,000 Jerry Garcia Band concerts existed on tape – as well as numerous studio recordings. Approximately 15,000 hours of his performances have been preserved for posterity. It has been said that the band performed “more free concerts than any band in the history of music.”

In one of the most epic careers in rock music, the band played at such iconic sixties rock events as the Monterey Pop Festival and Woodstock. In 1973, they performed with the Allman Brothers band for a show in upstate New York, before an estimated crowd of 650,000, memorialized in the Guinness book as the single largest audience at a musical event. And in 1978, they played a concert at the base of the Great Pyramids in Egypt.

Jerry’s prodigious output was not limited to the Grateful Dead. He formed his own band, The Jerry Garcia Band, with long-time collaborators, John Kahn, Meri Saunders and Melvin Seals, among others and the bluegrass act, Old and in the Way, with mandolinist David Grisman.

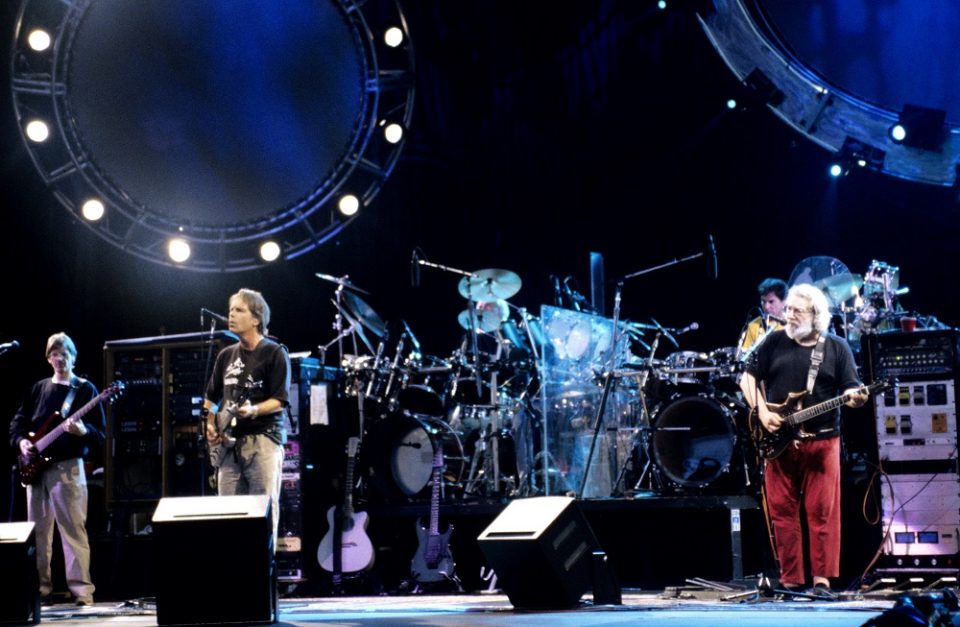

(L – R) Phil Lesh, Bob Weir, and Garcia of The Grateful Dead perform at Shoreline Amphitheatre on June 2nd, 1995 in Mountain View California. Photo: Tim Mosenfelder/Getty Images

One of his very last collaborations was on Calcutta-born composer and guitarist Sanjay Mishra’s album, Blue Incantation, a gorgeous set that effortlessly locates Indian classical music within a western context. On tracks like “Clouds and Monsoon,” Jerry’s bluesy riffs are worked into the song, evoking a rich, atmospheric palette while Samir Chatterjee’s virtuosity on tabla matches the layered texture of Mishra’s compositions. The centerpiece of the album is Sanghamitra Chatterjee’s intense vocals in “Passage Into Dawn,” an impassioned tribute to beauty and impermanence.

Garcia’s bargain with the devil finally ran its course when he was killed by a heart attack on August 9, 1995, barely a week after his 53rd birthday. But not before he had created an alternative American reality that still lives on through the vast ecosystem of bootleg recordings, folklore, lyrics and the Deadhead community.

As per his wishes, a portion of Jerry Garcia’s ashes were spread into the Ganges river in the holy town of Rishikesh by Bob Weir and his widow Deborah Koons, accompanied by Sanjay Mishra. The remaining ashes were scattered into the San Francisco bay.

We were exhausted, sweaty and exhilarated by the end of the show. We had flowers in our hair and stars in our eyes. During the course of the evening, Jamal had also met the woman who would one day become his wife and the mother of his children.

After the show, I vividly remember driving out on the New Jersey turnpike and feeling totally disoriented, like a rabbit in the headlights of oncoming traffic. For a few moments, I did not know who or where I was. Someone popped a tape into the stereo and the opening chords of “Ripple” filled the air. The music swirled through me and around me, every word an epiphany, every chord a revelation. Suddenly it all made sense again.

If my words did glow with the gold of sunshine

And my tunes were played on the harp unstrung

Would you hear my voice come through the music

Would you hold it near as it were your own?

It’s a hand-me-down, the thoughts are broken

Perhaps they’re better left unsung

I don’t know, don’t really care

Let there be songs to fill the air

Ripple in still water

When there is no pebble tossed

Nor wind to blow