Green Day Fight On

“Every song, every word, everything I write, every part of the music ”“ I completely throw myself into it,” Billie Joe Armstrong says, sitting in a soft chair in the downstairs den of his home. Green Day’s singer-guitarist and main songwriter lives in a neighbourhood perched on a hill east of downtown Oakland. A sliding […]

“Every song, every word, everything I write, every part of the music ”“ I completely throw myself into it,” Billie Joe Armstrong says, sitting in a soft chair in the downstairs den of his home. Green Day’s singer-guitarist and main songwriter lives in a neighbourhood perched on a hill east of downtown Oakland. A sliding glass door opens to a patio with an enviable view of San Francisco Bay, all the way to the Golden Gate Bridge.

But Armstrong is facing the other way as he speaks. And his gaze wanders up the cherry-red wall across the room, to large framed photographs of the Who’s Pete Townshend smashing a guitar in the mid-Sixties and a trio of very young Beatles ”“ John Lennon, George Harrison and original bassist Stuart Sutcliffe ”“ in Hamburg, Germany. “That is the thing that can fuck you up in the head,” Armstrong goes on at a machine-gun clip. “Here’s this thing, this freedom of rock & roll. I have the opportunity to express myself for the rest of my life, which is awesome. At the same time, I’m doing it as if my life depended on it.

“That’s the thing for me,” says the guitarist, 37, whose eternal-punk-boy features and modish haircut ensure he doesn’t look a day over 22, his age when Green Day’s 1994 album, Dookie, made them overnight punk-pop stars, selling 15 million copies worldwide. “I have to make sure that I’m completely lost in the moment.”

This is what he means: The night before, Green Day ”“ Armstrong, bassist Mike Dirnt and drummer Tré Cool ”“ play at Oakland’s Fox Theater. The gig is one of four surprise Bay Area shows to limber up for their first world tour since 2005 (they start in Seattle on July 3), and the two-and-a-half-hour marathon begins with a complete performance of the band’s new rock opera, 21st Century Breakdown. The album is a compound bomb of classic-rock ecstasy, no-mercy punk assault and pop-song wiles; it’s like the Clash’s London Calling, the Who’s Quadrophenia and Hüsker Dü’s Zen Arcade all compressed into 18 songs.

From the start, Armstrong is way gone. In ”˜21st Century Breakdown,’ he holds his guitar aloft like Bruce Springsteen and swings his power-chord arm in Townshend-style windmills. He pogos to the goose-step beat of ”˜Know Your Enemy,’ punches the air during ”˜East Jesus Nowhere’ like he’s boxing with God and leans over the lip of the stage for ”˜Horseshoes and Handgrenades,’ belting the line “I’m not fucking around!” eye to eye with the kids in the pit. Dirnt is a key voice in the weirdly sweet harmonies lacing ”˜Christian’s Inferno’ and ”˜Murder City,’ and Cool drives everything like Keith Moon with Charlie Watts’ swing.

Armstrong, who wrote virtually every note and word of 21st Century Breakdown, is the nonstop centre of the maelstrom ”“ all through a second set too, including hits from Dookie and the politically charged 2004 smash, American Idiot. And he pays for it. After the show, in a catering room backstage, dozens of friends and relatives cluster around Dirnt and Cool with congratulations. Armstrong, though, is a no-show. He stays in his dressing room, recovering.

“He must be exhausted,” says his mother, Ollie, a petite woman in her 70s with curly blond hair, a warm smile and, at the moment, a fretful-mom’s sigh in her voice. Billie is the youngest of her six children; their father, Andy, died of cancer when Billie was 10. “I worry about him,” she says of Billie. “He puts so much of himself into his music, into performing. It takes a lot out of him.” Later, Billie gets a text message from his sister Anna, who also waited for him backstage: “You have to make sure you take care of yourself.” (“I was like, ”˜I’m good,’ ” he assured her.)

Butch Vig, who produced 21st Century Breakdown with Green Day, recognises that kind of total immersion: He co-produced Nirvana’s 1991 album Nevermind. “I saw the same thing in Kurt,” Vig says, referring to singer-guitarist Kurt Cobain. “When he played, it was like he was free. And Billie Joe has told me that: ”˜When I’m onstage, I’m free. I’m not thinking.’ ”

Vig saw the downside of that intensity too. “They’d be working on a song, it wasn’t coming together, and Billie would get frustrated. He’d put his guitar down and say, ”˜I’m going home’ ” ”“ sometimes leaving Dirnt and Cool standing there. “Billie sets the bar high. He expects everybody to get there as quickly as he does. But Mike and Tré keep up with him. When they lock in, they play like no other band I’ve worked with.”

Cool, 36, describes Armstrong as “gifted and tormented. Billie’s brain is like 18 tape recorders playing simultaneously in a circle. Then he tries to have a conversation with me or Mike or his wife, Adrienne, at the same time. You can talk to him ”“ ”˜OK, what do you think of this?’ ”“ and he’ll be looking you in the eye, going, ”˜Huh?’ ”

Dirnt, 37, uses a similar metaphor: “Billie is not able to turn off the six different radio stations in his head.” The two met in fifth grade, at a school in Crockett, California, north of Oakland ”“ Armstrong is from nearby Rodeo; Dirnt was born in Oakland ”“ and have played music together for nearly as long. They started Green Day, originally called Sweet Children, when they were 15. (Dirnt’s real name is Michael Ryan Pritchard. A friend dubbed him Dirnt after the sound of his bass-playing.)

“We are a democracy with an elected leader,” Dirnt says of Green Day. He and Cool, whose real name is Frank Edwin Wright III, “are there to support Billie. Because he drives himself insane. We tell him, ”˜We’re here for you, man. We do not take lightly what you’re doing.’ ”

At home, says Armstrong, “I catch myself apologising a lot.” He pauses, grinning. “Not a lot,” he quickly amends. “Enough.” For a guy who freely admits he wants to be “the rock god from hell,” Armstrong strives for a normal family life. He and Adrienne ”“ who co-owns an organic clothing and furniture store, Atomic Garden, in Oakland ”“ have been married since 1994 and have two sons. Asked about his writing regimen for the new album, Armstrong says the first thing he did every day was “get up and see the kids off to school.” In baseball season, he is an assistant Little League coach.

Still, Armstrong concedes, “I will come to Adrienne once in a while and go, ”˜I know I’ve been completely consumed and self-centred. I’m sorry that for the last 15 years all I’ve talked about is being in a rock band.’ ”

“Billie is music,” claims Dirnt. (He and Cool also have two children apiece.) “If you took the music away from Billie, you would still have a good husband and father who takes care of business and is there for his kids.

“But the rest,” he says, “would be a shell.”

*****

On the way downstairs to the den, Armstrong points out some musical highlights in his home: on one wall, a framed print of Bob Dylan’s painting on the cover of his 1970 album Self Portrait; on another, a photograph of the members of Green Day and U2 re-enacting the cover of the Beatles’ Abbey Road, taken when the bands made a benefit single together at the London studio in 2006; and around a corner from the den, Armstrong’s home studio. At one point, as he worked here on songs for 21st Century Breakdown, Armstrong recorded a cover of the Who’s 1966 mini-opera ”˜A Quick One While He’s Away,’ singing and playing all of the parts.

“That song is one of the most perfect moments in rock theatre, more inspiring than Tommy,” he raves. And he can’t get enough of it. Green Day have cut a full-band version, available as an iTunes bonus track with 21st Century Breakdown. At the Fox Theater, they performed the entire piece at a soundcheck.

“It’s important to us that we’re still looked at as a punk band,” says Cool, who joined Green Day in 1991. He has his first drum kit, the one he played as the 12-year-old drummer in the Lookouts, set up in an attic room of his Oakland home. “It was our religion, our higher education.” Armstrong’s first favourite bands included Hüsker Dü and the Bay Area ska-punk group Operation Ivy. He fondly remembers his sister Anna taking him to see the Replacements when he was 15.

But recently, Cool says, Armstrong has “gone archival. He’s looking for the architects of rock & roll, like Eddie Cochran. He’s like, ”˜I’ve got this great obscure Creation record.’ ” While recording with Vig in Los Angeles last year, Green Day bought cheap turntables at Amoeba Records and lots of vinyl to play during breaks. Vig would arrive at the studio to work on guitar parts and find Armstrong spinning Eighties power-pop LPs by the Beat and the Plimsouls.

“Everyone’s gotta get their inspiration from somewhere,” Armstrong says. He talks excitedly about his research for 21st Century Breakdown, the records and artists he listened to on the way to his own songs: the Pretty Things’ 1968 concept album, S.F. Sorrow; Ray Davies of the Kinks (“I love how he can make everyday life sound so grandiose”); the Doors’ first two albums; Meat Loaf’s Bat Out of Hell (“Just because it’s so ambitious”).

“For me, it’s the whole aesthetic: harmonies, dynamics, swagger, fluidity,” Armstrong continues. To make your own rock & roll history, he contends, “you take all of those ingredients and establish them to your own life, your past.”

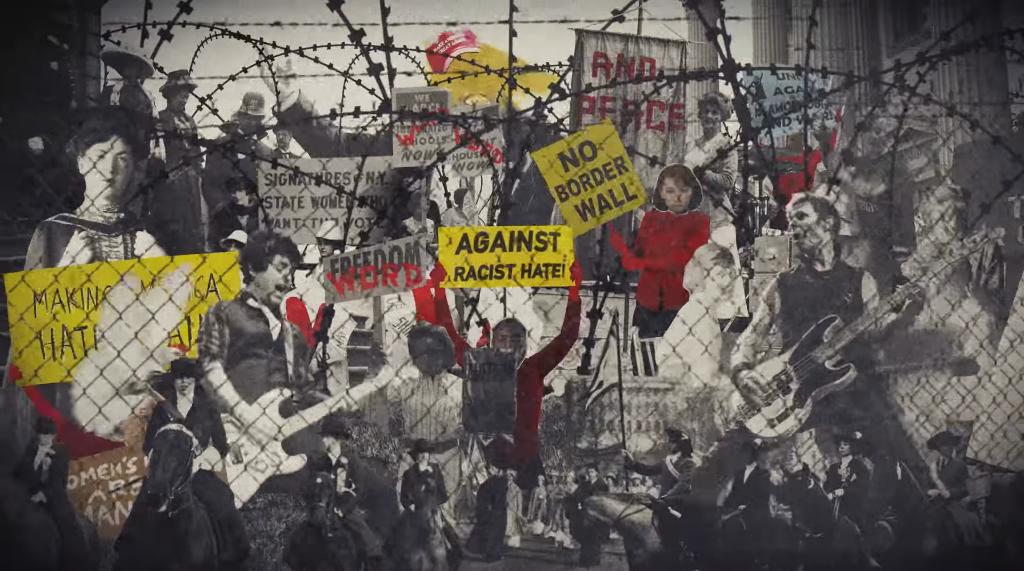

21st Century Breakdown is, like the anti-Bush vitriol of American Idiot, fiction set in current events: A punk-rock couple, Christian and Gloria, spin their wheels and fight their way through a new century already going terribly wrong. “We’re in a transition, from one destructive era to something new,” Armstrong says. “That is just as frightening as the past.”

But embedded in the howitzer riffing and shout-along choruses is the most personal, emotionally convulsive record Armstrong has ever written. References come from close to home, like “the Class of ’13” in ”˜21st Century Breakdown’ ”“ Armstrong’s older son, Joseph, 14, graduates from high school in 2013. Dirnt is certain the guitarist wrote ”˜Last of the American Girls’ about Adrienne: “She has very strong beliefs and stands up for the things she believes in.” Armstrong starts the title song with his own birthday ”“ “Born into Nixon, I was raised in hell” (he was born in 1972). When he sings about abandonment and vengeance in songs like ”˜Before the Lobotomy,’ ”˜Christian’s Inferno’ and ”˜Peacemaker,’ he does it in the first person. “You’d be surprised what I endure,” Armstrong croons in the Seventies-John Lennon ballad section of ”˜Restless Heart Syndrome,’ before the psychotic wah-wah guitar blows in.

“I don’t really know what I was setting out to do,” Armstrong confesses. For months, while Green Day worked on the music at Studio 880, their recording and practice facility in Oakland, then in pre-production sessions with Vig, Dirnt and Cool had no idea what Armstrong was writing about. “I wouldn’t tell them what the lyrics were,” he says. His demos were no help. Armstrong mixed his vocals so low, behind the guitars, Cool says, that he and Dirnt “could only understand half of what he’s singing.” Finally, one day last year, Armstrong sat down with Dirnt, Cool and Vig and read the words aloud to them ”“ every song, in order.

“I look at Christian and Gloria,” Armstrong says now, “and it’s me. Gloria is one side: this person trying to hold on to this sense of belief, still trying to do good. Whereas Christian is deep into his own demons and victimising himself over that.

“Sometimes I feel like I’m protecting my kids from myself,” he says quietly, as if he’s afraid Joseph and Jakob, 10, might overhear him. (They are at an Oakland Athletics game with Adrienne.) “I’ll write a song like ”˜Christian’s Inferno’ or ”˜East Jesus Nowhere’ and fear they will look at the lyrics. Even Adrienne will look at them and go, ”˜Is Dad feeling OK?’ ” Armstrong wrote ”˜East Jesus Nowhere,’ a scalding rebuke of fundamentalist religion, after attending a church service where a friend’s baby was baptised. The friend later asked him, “Was it really that bad?”

Dirnt says Armstrong, who dropped out of high school in 12th grade, always wrote with “seriousness, on a personal-politics level. ”˜Basket Case’ [on Dookie] is about someone trying to hold on to sanity.”

Cool recalls the way his dad, a Marine helicopter pilot during the Vietnam War, reacted to Armstrong’s rendering of a father’s absence in American Idiot’s ”˜Wake Me When September Ends’: “He was really moved. Because that’s what happened to my mom and him. They got married, she got pregnant and he got shipped off to Vietnam. That love story was his.”

Armstrong talks frankly about the roots of his discontent, like the “years of disconnection” in his family after his father died. “The problem was I had five parents: my older brothers and sisters” ”“ Alan, Marcie, Holly, Anna and David. “They were going through their own loss. Yet they had this responsibility toward me ”“ my mom had to work graveyard shifts as a waitress. The resentment grew. And I didn’t want to be a burden. I wanted to be a younger brother. It’s taken us a lot of years to get through that.

“But we’re all born with the same demons,” he argues. “I’ll see a kid at a show wearing a Green Day T-shirt and think, ”˜I wonder what’s wrong with him. What’s he going through?’ There is always that part of you, on the subterranean side of society. You don’t fit. You see things, and they make you angry. I internalise shit. And I spit it out.

“Ground zero for me is still punk rock,” Armstrong says heatedly. “I like painting an ugly picture. I get something uplifting out of singing some of the most horrifying shit you can sing about.” He smiles. “It’s just my DNA.”

Armstrong beams when asked if Joseph has finally heard the new album. “I had just got the mastering back, then had to split town,” he says. “Adrienne said it was so funny ”“ Joey and his friend in the car, headbanging the whole time. Sometimes I feel insecure ”“ I want to make sure ”˜Christian’s Inferno’ isn’t going on in this house. I don’t think he understands everything that’s going on in there. He just knows it rocks hard.

“But in the next few years,” Armstrong acknowledges with a slight shiver, “he’s definitely going to do some investigating.”

*****

”˜I could tell you what every street is down there,” Dirnt says, turning on a stool at a small table next to his kitchen, looking out the glass door to a patio. The bassist lives with his wife, Brittney (they were married in March), their new son and his teenage daughter by a previous marriage in a house that sits on a ridge high over Oakland, near a state nature preserve. Dirnt often goes out back in the morning, in his bare feet, and scans the rolling hills for coyotes, foxes and bobcats.

The view from the patio, though, is even better than Armstrong’s. Dirnt can see not only the whole of San Francisco Bay but, right below him, his entire life story and Green Day’s early career: the houses, hangouts and clubs in Oakland and Berkeley where he, Armstrong and Cool partied and played before stardom. “I’ve ridden my bicycle on every street,” Dirnt says. “I was born over there” ”“ he points to the left ”“ “a little to the northeast of downtown. It’s called Oakland Highland. Nowadays, if you want to get shot, go to Oakland Highland. They’re used to dealing with the trauma.”

Green Day are global rock stars. The next-to-last show of their American Idiot tour, in December 2005, was for more than 50,000 people in a cricket stadium in Sydney. But Green Day consider themselves a local band. Armstrong and Dirnt grew up in the East Bay area. Cool moved to Berkeley from rural Mendocino County when he was 17. In the late Eighties and early Nineties, they were regulars in the audience and onstage at the 924 Gilman Street Project, the legendary punk co-op in Berkeley. Armstrong wrote much of Dookie in a house he and Cool shared with other musicians and itinerants at Ashby Avenue and Ellsworth Street in Berkeley. Dirnt lived nearby, on San Pablo Avenue, although Armstrong points out, “Mike’s lived in every single town around here: El Cerrito, El Sobrante, Rodeo, Crockett, Albany, Berkeley. He’s been everywhere.

“This is home for us,” Armstrong says of Oakland, “just as much as New Jersey is for Springsteen and Dublin is for U2. We represent it. We’re trying to, anyway.” Armstrong, Dirnt and Cool live within 15 minutes’ drive of one another. Cool has a house on a quiet, tree-lined street much closer to sea level. (He has a girlfriend, Ruri, and a teenage daughter and young son by earlier marriages.) When Green Day are not on tour, they commute regularly to Studio 880, located almost under a freeway in the rough Jingletown section of Oakland. The band’s idea of a vacation, during rehearsals for 21st Century Breakdown, was to write and record an album there of Sixties garage rock as Foxboro Hot Tubs. When people ask Dirnt, “Do you have any advice for my son? He wants to be in a band,” his stock response is “Play with your friends.”

Armstrong and Dirnt were “inseparable,” the guitarist says, from the moment they met. “Both of us felt a void in our lives at the time.” Armstrong’s father was dying; Dirnt, who was adopted, was bouncing between his divorced parents. At one point, Dirnt, a champion class clown in school, moved into Armstrong’s house. “He was a super-high-strung kid,” Armstrong recalls, “talking, insulting people nonstop.” One of Armstrong’s sisters, meeting Dirnt for the first time, chased him around the kitchen with a butcher knife. “I thought, ”˜That means you’re part of the family,’ ” says Armstrong.

Cool was the most experienced musician in Green Day when he replaced their original drummer, John Kiffmeyer, in time to play on the 1992 album Kerplunk. Two years after Cool was born in Frankfurt, where his father was stationed, the family settled on a remote mountain near Willits, in Northern California. One of the few neighbours was Larry Livermore, a punk in his 30s when he started the Lookouts with the preteen Cool in 1985. Livermore also co-founded Lookout Records, which issued Green Day’s earliest records.

“What struck me about Billie first was his melodies,” Cool says. “He wasn’t screaming as many syllables as you could get in a note. He had this Beatles vibe about him.” Cool had trouble fitting into Green Day at first. Dirnt and Armstrong “had a Paul-and-John thing going,” meaning McCartney and Lennon. Asked who was who, Cool replies, laughing, “I still don’t know. I think Billie is Paul and John now.”

“We weren’t used to someone with that much high energy,” Dirnt says of Cool, which is rich coming from the fast-talking bassist. “Honestly. We’d wake up on tour, and he’d be going first thing in the morning, talking loud. When he was younger, his voice was a lot higher. I’d go, ”˜Dude, shut the fuck up. I’m gonna kill you.’ ” In his defence, Cool calls Dirnt “a mean sleeper. Anything for Mike in the morning is a drag. Nobody wants to wake him up. You have to poke him with a long stick and still know where the door is.”

Armstrong is Green Day’s king songwriter, but there is plenty of truth in the credit line on the band’s albums, all music by green day. Armstrong, Dirnt and Cool arrange everything together and rehearse the results with almost military intensity. “They share a sensibility that only comes from time, being so close for so long,” says Vig. 21st Century Breakdown is the first record he’s made with Green Day. (Most of their previous Warner Bros. albums were produced with Rob Cavallo.) But he first met them when Green Day and Vig’s band Garbage shared some European festival bills.

“They were their own little gang,” Vig says. “They would finish each other’s sentences. And they were incredible players. When they do that Green Day thing ”“ that uptempo, super-locked-in rhythm ”“ Billie almost turns into a machine.”

“We still move at breakneck speed ”“ we wait for no man,” Dirnt declares cheerfully. “There is a kid inside each of us that is more substantial than most of the people we grew up with ”“ or most people who grew up in functional families. I feel like a good test to see if an adult has lost their inner child is if they don’t have a lucky number anymore or a favourite colour.

“I still do. My lucky number is 11. My favourite colour is a dark shade of blue.”

*****

”˜OK, requests!” Armstrong shouts. “It’s request fucking hour!”

The night after the Fox Theater show, Green Day are onstage again ”“ across the street, crammed onto the tiny stage at the Uptown Bar, playing for a cheek-to-jowl crowd of about 220 people. The band performs all of 21st Century Breakdown again. Then Armstrong throws the second-half set list away, breaking out a Buzzcocks cover and leading the band through a sizzling portion of David Bowie’s ”˜Ziggy Stardust’ (“We’re capable of playing 30 seconds of any song, ever,” Armstrong crows). When someone in the audience yells, “Cheap Trick!” Green Day launch into a fantastic medley of ”˜Surrender’ and the Replacements’ ”˜Bastards of Young,’ pingponging between the choruses of each song.

“I feel like I’ve deprived myself for the past three years,” Armstrong says that afternoon before the show, referring to the time Green Day laboured on 21st Century Breakdown. “I get onstage, and I feel completely in my element, totally happy. This is where I belong.” And that is where he and Green Day will be for at least the next year.

Actually, it doesn’t take much coaxing to get Armstrong to talk about the ideas piling up in his head for another Green Day album. The most fanciful one: “I’d like to make a record in China. I’d also like to see Mike become more of a songwriter. I’d like to strip things down, become more acoustic ”“ see how quiet we can get and still have the drama and power behind it.”

Armstrong is already involved in a theatrical adaptation of American Idiot, directed by Michael Mayer and opening September 4th at the Berkeley Repertory Theater. “Billie is very much a part of it,” says Mayer, who directed the Tony Award-winning Broadway musical Spring Awakening. “I keep e-mailing him different versions of my scenario ”“ he is totally into the experiments I want to do.” Recently, Mayer says, Armstrong told him, “ ”˜The next thing I want to do is write something completely new for you to direct.’ ”

“Right now, he’s cursed with a new song in his brain, I’m sure,” Cool says. “He can’t quiet that.” But there is a hint of worry, of nerves, in Armstrong’s constant excitement, as if he can’t stop running for fear of falling behind. The guitarist tells a story about a school friend, James Washburn, who took a copy of Green Day’s first album into English class shortly after it was released.

“I’d already dropped out,” Armstrong recalls. “He said to the teacher, ”˜Look what Billie just did.’ The teacher looked at it and started correcting my spelling on it.” Armstrong makes a grim chuckling noise. “That can make someone feel pretty insecure and vulnerable.

“Maybe that’s the reason most people don’t go for it,” he says. “You can scare yourself with ambition ”“ having the audacity to want to be as good as John Lennon or Paul McCartney or Joe Strummer. There has been so much great shit before me that I feel like a student: ”˜Who the fuck do I think I am?’

“But you have to battle past that,” he insists in his rapid forever-punk chirp. “It’s the people who are overconfident who are the ones putting out the biggest piles of shit. If you’re at that place where you’re working hard but don’t feel like you know what you’re doing anymore, then you’re on to something.”

Armstrong can’t say if Green Day’s next record will be another concept monster or just a hip bunch of punk songs. But he will know the idea when it comes, “because it hits me over the head like a ton of bricks. And it’s not just an idea. It’s an obsession.”