‘Leaving Neverland’: Sundance’s Michael Jackson Doc Leaves Audience Shellshocked

Premiere of Dan Reed’s two-part, four-hour exposé — in which two men allege the King of Pop sexually abused them — is a bombshell

There was no gaggle of protestors outside the Egyptian Theater in Park City, Utah early Friday morning, despite news reports that the Sundance Film Festival had been told to brace for a massive disruption on Main Street. There were, however, policemen patrolling the area with bomb-sniffing dogs, three times the usual security of a typical screening and, per Festival Director John Cooper, “healthcare professionals in the lobby” in case anyone bothered by the material needed to talk to someone immediately.

The warning to the packed house was warranted: Leaving Neverland, Dan Reed’s two-part, four-hour documentary focusing on two men who claimed that Michael Jackson had abused them as children, opens with a disclaimer about “graphic” descriptions of sexual acts involving underage participants. And after hearing these subjects recount in horrifying detail what they say took place in various hotels, houses and on the Neverland Ranch, it’s hard not to feel that you’ve experienced post-traumatic stress disorder yourself. During a 10-minute intermission, audience members appeared slightly dazed. By the end of the screening, the crowd looked completely shellshocked.

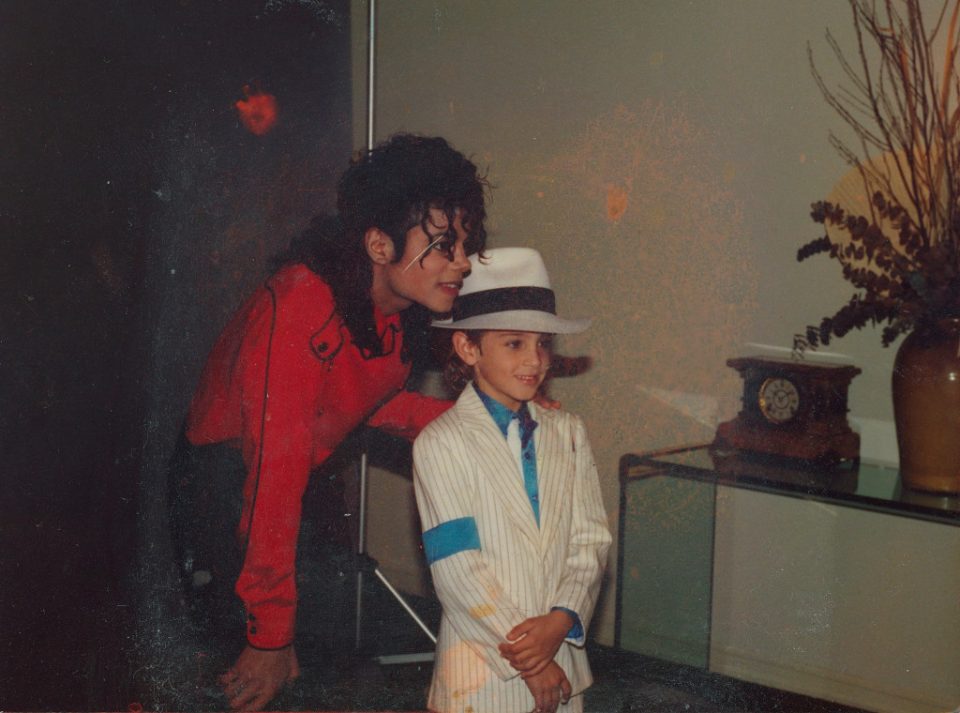

Centered primarily around extensive on-camera interviews conducted with Wade Robson and James Safechuck ”” with additional testimonies from their family members and spouses ”” Neverland begins with the two men recalling their first encounters of the King of Pop. For Robson, an Australian kid who became enamored of the singer after his mother Joy brought home a “Making-Of Thriller” videotape, hearing Jackson’s music for the first time led to obsessively studying the artist’s moves; after getting first prize at a Jackson-themed dance contest at a mall, he won the chance to meet the man himself during a concert stop in Brisbane. He was eventually pulled onstage to perform his moves for the crowd and spent time with the pop star at his hotel before Jackson left. If you’re ever in America, Jackson tells the Robson family, look me up. That would eventually lead to Joy, Wade and his sister being invited to spend time at the ranch later on. By this time, the child had permed his hair and taken to wearing carbon copies of Jackson’s outfits. He was seven years old.

As for Safechuck, a gig acting in a Pepsi commercial ”” in which he sneaks into Jackson’s dressing room, trying on the singer’s sunglasses until the man himself shows up ”” brought him into the singer’s orbit. Unlike Robson, he wasn’t a superfan; like Robson, he was immediately enamored of the pop superstar paying attention to him and making him feel “important.” Jackson also befriended the family, often having dinner and movie nights at the Safechuck house in Simi Valley, California. He flies the family to Hawaii during a Pepsi convention, and invites the boy to sleep in his hotel room. On the flight back, you can hear the singer flattering James to an unusual degree. Jackson invites the family to his pre-Neverland estate, eventually convincing the Safechucks to let James stay there on his own with the singer. He was 10 years old.

Neverland keeps cutting between these two stories, as the men begin to recall how the singer would allegedly initiate physical contact during “sleepovers” and “escalate” things from there. The stories suggest a similar pattern of childlike playing, followed by claims of grooming, mutual masturbation, further sexual advances and long lectures from Jackson about how you couldn’t really trust your parents, and you definitely could not trust women. Gifts, trips and other high-life perks are lavished on family members, yet both boys’ mothers recall how they’d consistently be separated from their sons whenever the chance arose. Safechuck recalls how Neverland Ranch was set up with a series of tucked-away bedrooms and secret rooms where these alleged sexual activities could take place without folks knowing. Robson, who Jackson nicknamed “Little One,” describes a “secret wedding” between the two.

And both men recall how, according to Robson, “in the context of what was going on, this all seemed normal”; how they were told this was how you showed someone you loved them; how they could never tell anyone, because both they and Jackson would be thrown in jail; and how each became jealous when other boys replaced them as objects of affection.

The doc’s second half then starts with the 1993 case against Jackson by 13-year-old Jordan Chandler, who claimed that the singer had molested him when he was staying at the ranch, and why both Safechuck, Robson and their families felt compelled to testify on his behalf. By the time further allegations prompted a criminal trial, Safechuck told his mother that Jackson “was not a good man” and asked that they refrain from aiding the defense.

Robson, however, did; one of Neverland”˜s most painful sections finds the now-successful choreographer and ”˜N Sync/Britney Spears collaborator worried that his career might be tainted, Michael’s children might never see their father again and that he felt he needed to protect Jackson ”” all this despite what he claims had happened to him. After Jackson’s death in 2009, both men have married and have become fathers; they also find that they can’t sleep at night and are suffering from various PTSD symptoms. They eventually begin to refer to what happened to them as abuse. Things get worse before they start to get better. (Both Robson and Safechuck admit they initially denied the allegations due to what they said was a need to compartmentalize the alleged abuse.)

By the time the credits rolled, the energy in the room hovered somewhere between queasiness over what we’d just witnessed and the sense that some sort of turning point about how these accusations play into Jackson’s legacy had been reached. By offering these men a forum, this doc has clearly chosen a side. Yet the thoroughness with which it details this history of allegations, and the way it personalizes them to a startling degree, is hard to shake off. It does not discount what these men say, nor does it leave out the fact recent lawsuits muddy the waters a bit.

But the film shows how sexual abuse leaves psychological scars, how fame can be seductive enough to warp moral compasses (especially regarding the parents) and how complicated things can be when you love someone who may be hurting you. It’s also a portrait of a man who was many things to many people, and how that image may not sync up with what some folks want to believe.

And it’s a portrait of bravery, as evidenced by the fact that when Reed brought Robson and Safechuck to the stage after the film, the three men received a minute-long standing ovation. Both men say that “what happened, happened,” and that they can no longer confront Jackson about it or get closure. Both talk about still being in the process of healing, and both said they wanted to do this so that, should someone else be dealing with the aftermath of abuse, they too could come forward. (One audience member confessed about his own molestation as a child and thanked them for making the film; another mentioned that, as a lawyer who’s dealt with many sexual abuse cases, this could help change the law regarding such crimes.)

When folks staggered out onto Main Street shortly before 1pm, greeted by several people holding a few “Michael = Innocent” signs, it was hard not to feel different about the man at the center of the film. It was hard not to feel like a bombshell had been dropped.