Mark Knopfler’s Second Act

Since he walked away from the Dire Straits in 1995, the guitarist has found a new, quieter career as one of rock’s greatest songwriters

A few days later, Knopfler and his band take off in a leased Embraer Legacy corporate jet for Poland to resume the tour. Knopfler’s sidemen, some of them players he has worked with going back to the Dire Straits days, sit in the front of the plane, while Knopfler, his manager Paul Crockford and I sit in the back. There is laughter and easy banter all around, and that slightly anarchic vibe of men leading what is in some ways a boy’s life ”“ blue jeans and iPods, plenty of snacks, plenty of beer. Knopfler, for his part, floats in this atmosphere, and the look of purposeful serenity on his face reminds me of the expression in an animal when it is returned to its natural habitat.

When we land in Warsaw, we are met by a couple of cars and whisked to the sports arena where Knopfler will be playing tonight. It is a stark, bare-bones venue, with cement-and-plywood bleachers, long, windowless corridors, acoustic tiles hanging from the ceiling and an air of collectivist utilitarianism, but Knopfler seems at home here. If any part of him feels that this is a bit of a comedown from the era of playing supersites, there is nothing in his demeanour that betrays it.

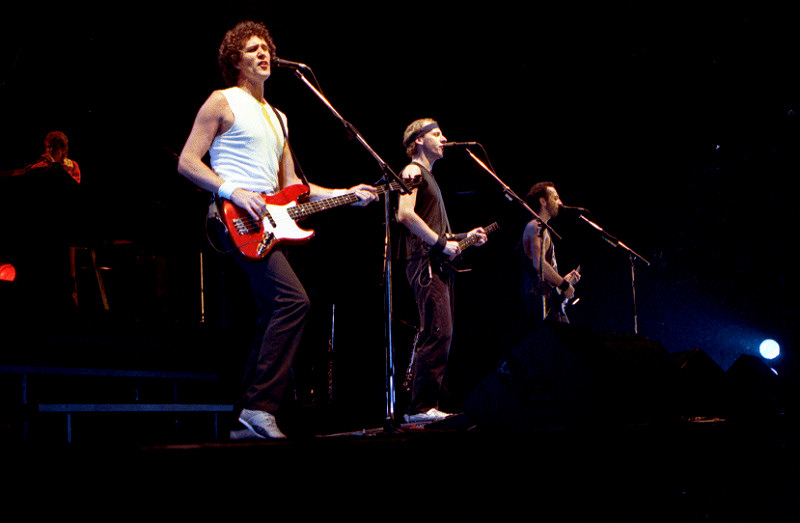

There are about 5,000 people here tonight, many standing in the gymnasium’s centre court, cellphones aloft. Knopfler begins the set with an old one, ”˜Once Upon a Time in the West.’ On the way to Warsaw, he said, “I can’t listen to my early records. It sounds as if I’m trying too hard. I’m overplaying, and my singing is sometimes sharp. But I do like to play the old songs, and people come to hear them. But the trick is to play them without making it some kind of cabaret.”

His renditions of ”˜Sailing to Philadelphia’ ”“ his strange and moving song about Mason and Dixon, and possibly the greatest song ever inspired by a Thomas Pynchon novel ”“ and ”˜Romeo and Juliet’ are electrifying in both emotional impact and sheer beauty. When Knopfler sings, “All I do is kiss you/Through the bars of this rhyme,” a collective shiver goes through the audience, though he is singing in a language that most of the crowd must struggle with, if they know it at all.

What they don’t have to struggle with is the sight of Mark Knopfler picking up his National steel guitar; as soon as it is handed to him, the arena fills with a collective roar, and that level of adoration is sustained through the rest of the two-hour show.

After the encores, Knopfler steps to the lip of the stage and holds his arms out on either side of him while swaying back and forth, like a man balancing on a tightrope. The Warsaw crowd continues clapping and cheering, snapping pictures with cellphones, but now all there is to photograph is the crew unplugging amps. Knopfler and his band have left the stage, left the building, and are, in fact, racing to the airport, where the plane awaits them. They haven’t bothered to book hotel rooms in Warsaw; tonight they will sleep in Berlin.

“This tour is the best yet,” Knopfler writes me later. “The band hardly ever plays the same thing twice, so I’m always getting new phrases to bounce off. I’m playing OK and enjoying singing more than I used to as it’s 11 years since I smoked a cigarette. There’s a terrific feel in the group. We travel together and eat together and the same kind of humour prevails. I feel very much at home being captain of my little ship.”