With the release of a new doc, one of music's most polarizing figures delves into her many controversies and life before the "woke" era

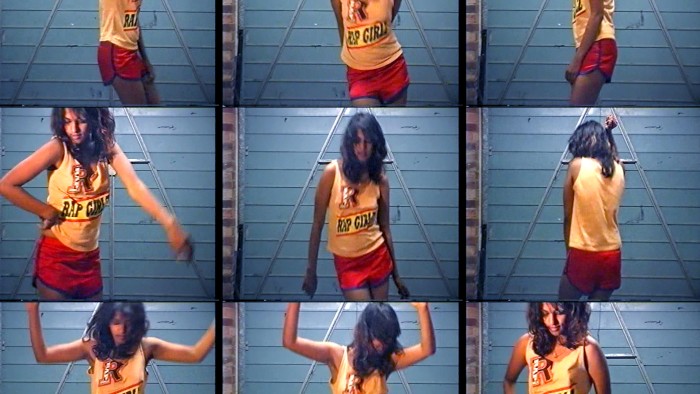

M.I.A. discusses the film, 'Matangi/Maya/M.I.A.,' as well as the fallout that followed her after she gave the world the middle finger at the Super Bowl. Photo: Courtesy of Cinereach

It’s the New York premiere of Matangi/Maya/M.I.A., a documentary about the controversial Sri Lankan”“British rapper who variously goes by all three of those names, and the Museum of Modern Art is bustling with noise and revelry. M.I.A., however, looks unusually serene. Dressed mostly in black, save for an ornately detailed hoodie underneath her jacket, she looks almost incognito ”“ a far cry from the kaleidoscopic, neon spectacles that have defined her look in years past. She hangs back in the VIP lounge, which is starkly black and white aside from a purposely garish arrangement of tabloid front pages from the New York Post in the mid-Eighties, and makes small talk with people before going into the theater to introduce the film with its director, Stephen Loveridge.

It’s been a couple of months since the film got its first screening at Sundance, where M.I.A. reacted with shock to the doc. Loveridge ”“ a friend of hers from art college, where she studied to become a documentary filmmaker herself ”“ had spent years sifting through around 900 hours of footage she gave him from throughout her life. She saw the 90-minute movie, which traces her life from about age 11 to the present with a heavy focus on activism, her feelings on being an outsider and her connection to the civil war in Sri Lanka, for the first time at the film fest and she was not bowled over by it. “That wasn’t the film that was supposed to be made,” she awkwardly told Loveridge in front of an audience after the screening. “I gave you some tour footage, and I asked him to cut it. You don’t mention about live shows.”

She’s still making sense of it. At tonight’s gala, which kicks off Film Society of Lincoln Center’s New Directors/New Films festival, she says she’s still unhappy about the secretive way Loveridge disappeared with her footage for months on end without checking in with her. “I didn’t know what Steve’s idea was for the film, because he made it here in New York,” she says. “I had to get a visa to come here, so I saw it when everybody else saw it. It was a lot to process. It was a lot to take in. This was very personal.”

Loveridge, who knew M.I.A. had a cache of footage, began work on the film in 2011 or 2012, when the artist was working on her fourth album, Matangi. He took it to her record label and management, but he felt Interscope was influencing its direction. “There are so many serious things in there, it belongs in a different space and shouldn’t be a promo piece to try to sell a record,” he says. So he shut down production and shopped his footage to companies that distribute arthouse documentaries. He then refocused the film to be more about the backstory of her family ”“ her father led the Tamil resistance in Sri Lanka ”“ and her character. “It was giving context on who she is as a person and what her life journey has been,” he says, adding that he still has enough footage to make the sort of tour documentary she was expecting to see at Sundance.

The film includes footage M.I.A. shot before she became a musician of her grandmother in Sri Lanka, who told her that to be happy she should sing every day. It has scenes she shot while on tour with Elastica, whose frontwoman, Justine Frischmann, loaned M.I.A. the groovebox sampler she’d use to write her debut, 2005’s Arular, and it features lots of footage about her endless stream of controversies, from blasting New York Times writer Lynn Hirschberg online over an unflattering profile to defiantly thrusting her middle finger at the world at the Super Bowl. The latter sequence shows how her mood shifted from pride to uncertainty ”“ as well as the bullying way the NFL confronted her about it directly after, leading to a multimillion-dollar lawsuit. And while it doesn’t focus much on her tumultuous relationships with DJ Diplo and Seagrams heir and her ex-husband Benjamin Bronfman, who is the father of her son, it serves as an in-depth portrait of M.I.A. as a person as much as an artist.

Loveridge says M.I.A. likes the film now (even if she doesn’t tell Rolling Stone so) and that her initial reaction didn’t bother him. “I’m used to her,” he says. “I’ve known her for a long time. I knew she was going to have a problem. I wouldn’t give my entire life over to someone, but she said, ‘Just go for it. I’m not even going to watch these and see where I’m naked or where I’m saying idiot stuff.’ She literally gave me boxes of things. So the trust was really incredible.”

After M.I.A. and Loveridge introduce the film, she returns to the VIP area to tell Rolling Stone what the film got right about her and what it got wrong. Although she is guarded at first, choosing her words gradually and looking around the room when answering questions, she slowly opens up.

What did you not like about the film at first? Was it too personal?

I don’t know. I feel like I’m the fish-man from The Shape of Water, and you need to show all the information to make people understand why you’re the fish-man. So on one hand, it’s very personal but on the other, maybe it’s helpful.

What did you learn about yourself from watching it?

I’m not sure, but I was surprised by some of the shots in there, footage I didn’t know existed. I don’t know how Steve found them. I don’t remember my grandma telling me to be a musician.

Then the way he told the story made me see how that maybe I was supposed to be a musician, as opposed to a documentary filmmaker. When I stepped into music, I was walking through it very fast and not processing, “Maybe that’s what I was supposed to do.” When I see the film, it seemed like I couldn’t get away from being a musician, whether it’s because I fell in with [Elastica’s] Justine, or whether my grandma told me or whether I was going towards it anyway.

When did you accept that you were a musician?

When I made [2013’s]Â Matangi.

That’s a long time into your career.

I accepted it on the outro of that album.

Why did it take you so long?

I don’t know. I think I needed it explained properly, because I went to art school and I felt that the medium you used to get your message across is a secondary thing. We could have done it through anything. I thought, “Our music is what’s working. It’s fast and it’s instant.” It was the thing that clicked with people. But I always wanted to make a film. So … I just never really fit in properly.

Feeling out of place is a major theme in the film too.

Yes. Hence the fish-woman thought from The Shape of Water.

Did the documentary give you a new perspective on not fitting in?

Well, an interesting thing that’s not in the film is the political changes that have happened. I think it’s kind of weird when those things are very important ”“ like discussing and finding everything [about politics] on Twitter and social-justice warriors are picking apart the thing ”“ and this film zooms in, and it doesn’t have a reference of time, apart from the [Sri Lankan] civil-war ending. So it’s not that you’re not fitting into the music industry alone. It’s not just that.

The film instead focuses a lot on the dust-ups, like Lynn Hirschberg’s New York Times article that shook you up because she claimed you didn’t know what was going on in Sri Lanka. How do you feel watching that?

Well, the Lynn Hirschberg bit to me is a bigger thing, because it has to do with what was happening to journalism at the time. The film didn’t have the context of when it was happening or why it was happening. Journalism pretty much changed around that time. You don’t really get a sense of how the Internet changed things in the film.

The Lynn Hirschberg thing happened at a time when you used to trust the old media. I was trying to raise points about how the new media is working, because you see it from real-life experience of how war is going down, and I made observations and then was criticized for making observations, because you’re expected to be a dumb musician and not have that insight and foresight.

Do you look at that period differently now?

Yeah. I’m not, like, particularly concerned about Lynn Hirschberg. It’s more about what happened to journalism on the planet from that year on and what that meant to the rest of the world and little people around the world ”“ people like me, who are trying to have a voice and to communicate something that was happening very far away from America.

Another point the doc addresses in depth is the way the NFL treated you after you flipped the world the bird at the Super Bowl. In the film, you say they were treating you worse than the way people treat murderers. Has that had any resolution?

No, I mean, I was with Roc Nation at the time I was negotiating that [NFL dispute]. They thought the best legal way to solve that was to sign on the dotted line to whatever terms the NFL wanted to put on me, which was basically to be a lifelong slave forever and to give a hundred percent of my earnings to them until I die. You wouldn’t think somebody would write something like that, but somebody did, and it wasn’t that long ago, only in 2013. Nobody thought that was wrong. And it happened because you’re a woman ”“ a brown woman ”“ and you did something very silly. And it was so threatening that the punishment for it was to basically lock you into this thing forever.

It was so crazy to me but everybody thought that was fine. I’m glad I left Roc Nation and I fought that on my own, with my own lawyer, because nobody stands up to these people. Nobody stands up to the NFL. Now they have, but it’s been four years. Since then, everyone has grown a backbone to stand up to the NFL and to have activism and to speak about things and to stick up for women. And none of this was around in 2013. At the time I was fighting cases in my work and in my personal life. My baby was about to get taken away. And no women came to my rescue to go, like, “Wow, you’re really heavy-handed on this woman who hasn’t killed anybody.”

A lot has changed since then.

For me, it’s interesting to see that in the past two years, everything has turned around in America. Within two years, the human brain can deal with racism, sexism, activism and all the “isms.” And they’re so “woke” to it. And they weren’t woke to it four years before, when it was happening to me. So to me it’s interesting to be back here [in America] and show this film and to get some sort of an idea of why there was this weird miscommunication happening. And oppression is oppression. Slavery is slavery. Being heavy-handed on somebody legally and not giving them rights, these are thing that happened to me in America.

I just feel like that is probably because they see me as an outsider. So it’s very interesting watching it from England where everyone on social media is like, “We totally empathize with women.” But it’s very difficult for them to empathize with me who’s been a musician for 20 years and to have been living in England and America and I can’t get the same sort of support. So [this film] helps me think about these things.

Meanwhile, the situation with immigration around the world has just gotten worse.

Everything has gotten worse. That’s the point. They kicked me out, saying, “You’re the worst thing that’s ever happened to society. You need to go.” And since then, everything has just become more divisive. IQs have dropped. No one’s been challenging enough to push the boundaries. And Donald Trump’s wall shopping, and immigration is crazy everywhere.

It’s not just in America. We have had Brexit, and all across Europe we’ve had all the right-wing people. And the immigration issues, in terms of people coming in boats and actually dying … there’s a scene in the film where I say, “Yeah, I’m gonna go back to college and become nautical engineer [to help refugees].” I’d said that before people were drowning in the Mediterranean. That was one of the things I learned [from watching the film]. I was like, “That’s weird, because I kept thinking that.” And that was 2013, before going through the NFL thing, and then by 2015, that was a serious, serious issue. It’s still happening now.

But yeah, it’s annoying. It’s annoying that that even in music, at that time, they’re like, “You need to go away, because you’re problematic. But we will have lots of other girls from anywhere in the world, we don’t care, they’re just not being problematic.” Since I left, there hasn’t been anyone talking about these things. So it’s very annoying to come back to be like, “Yeah, it’s me again.”

But, speaking of coming back, aren’t you retired from music?

I don’t know how to answer that question.

You’d said AIM was your last album.

I want to [retire], and I have said I am. And, yes, that is as much as I have to say. And it’s time for new people to come through, but that’s very difficult. It’s a very difficult thing. Because actually I think it’s harder now than it was for me 15 years ago, which is crazy. It’s really nuts.

And it’s just a whole different world.

And it’s not good. The future cannot be like this. I thought that was the positive thing about what was going on in America, that people would look more into worldlier things, and it’s really about a mindset and some philosophy, rather than us being divided by religion or color or gender. That will come about when certain types of people just allow themselves to be open to things and just evolve. Hopefully, it gets there.

The star enlisted Shaboozey, Post Malone, and her daughter Blue Ivy to debut tracks from…

Imagine 'Raging Bull' starring a CGI bull, and that gives you a sense of this…

This holiday season brings new tunes from Indian artists, including These Hills May Sway and…

As the credits roll signaling the end of 2024, here are some of the films…

Punjabi hip-hop artist part of hits like AP Dhillon, Gurinder Gill and Shinda Kahlon’s ‘Brown…

When Chai Met Toast, Madboy/Mink, Dualist Inquiry and more will also perform at the wine…