Pop Stuff: Death Becomes Us

On the 61st NYFF and a 2023 that brought a strange bounty of death at the movies

Death is the last taboo. From our early childhoods, religion, history classes or the passing of an aging grandparent conjure flights of angels, scenes of war or the memory of papery skin in a casket or on a pyre, but rarely do we actually discuss the reality. Former soldiers, often conscripted without regard for their morals, are left to fumble through the PTSD of post-war memories. When a family member has a long, lingering illness hushed rooms become the norm and a child’s untimely death can be met with deafeningly quiet condolences. Suicide, the biggest taboo within the taboo, remains largely shrouded in the hyper-silence of shame – unspoken despite the fact that more people take their own lives every year than die from car crashes. Paradoxically, we’ve made the things that leave the deepest scar the hardest experiences to share. Death is our only guarantee in life and yet it is the thing we won’t discuss around the dinner table, until we’re forced to confront it, like people groping in the dark.

Art shines a light in this darkness and while there’s no shortage of music, literature and painting that grapple with the truth of death and allow contemplation, cinema lags behind, tip toeing gingerly around real depictions of death and going whole hog into their caricatures. The movies have brought us bloodshed as sport à la Terminator and Kill Bill, war epics from Lawrence of Arabia to 1917, ghouls and horror galore from Carrie to Midsommar to Get Out. And who hasn’t seen a biopic that captures the death of a great figure in a single frame while exalting or dissecting their life for a solid two hours, as if we too will spend most of our lives living and next to none of it dying. As a visual collective medium, and one that walks the line between art and entertainment, films have responded to our need to consume vitality, not process dying. We come to films to exalt in screen idols who defy aging and when we do confront death in the movies, it’s often at such a remove from real life experience that we can walk out of the dark and say it was just a movie. But it’s possible that a collective on-screen contemplation of death’s depths could feel as healing as reading Didion’s The Year of Magical Thinking or as moving as viewing Picasso’s Guernica solo in a museum. This past year the movies seem to have come around to that idea and brought a strange bounty of death in film. My most enriching movie watching experiences from the 61st New York Film Festival, a year’s worth of films in a fortnight in October, grappled with death again and again and in ways that felt as honest as they were creative, shocking and moving. In prior years a singular film might confront death or aging this way. Dementia in Gaspar Noe’s harrowing Vortex, elder love in Michael Haneke’s devastating Amour and genocide in Joshua Oppenheimer’s The Act of Killing, all spring to mind. But 2023 brought a surfeit, and staring down the inevitable at the movies came with its own catharsis.

Take Bradley Cooper’s Leonard Bernstein biopic Maestro in which he directed himself in the titular role. Despite the early drama over whether his prosthetic nose was a little much, the image that lingered for me was the always excellent Carey Mulligan as Bernstein’s long suffering wife Felicia Montealegre Bernstein, an actor and passionate activist. Cooper, who co-wrote the film with Josh Singer, tilted the focus away from Bernstein’s prodigious career and towards his marriage, a call that paid off. After exploring the power balance of artistic couples in A Star is Born, Cooper seems to be making the subject a theme of his directing life. In Maestro, although it’s Bernstein’s career that overshadows his wife’s, the real destabilizer is neither Bernstein’s talent, nor his closeted homosexuality, but Felicia’s illness. The movie’s beating heart becomes Felicia’s struggle to survive a cancer diagnosis and the mark of that on her husband. We see her shrink on the screen – the jewelry, the fabulous clothes, the coiffed hair giving way to muted sweats and a skull cap. As Felicia recedes into, and finds comfort in, her children and once fraught marriage, Cooper really lingers on her final days. When Leonard Bernstein holds his wife’s frail frame, we ask ourselves – who will we hold and who will hold us?

Conversely, in Oppenheimer, the year’s other much talked about biopic, Christopher Nolan expands on J. Robert Oppenheimer’s life, while not doing as much to capture the many deaths that spiraled out of his work. The film exemplifies Nolan’s great skill as a writer-director in revealing the physicist known as ‘the father of the atomic bomb’, but glosses over the dark core of his work’s complicated legacy where it concerns the bomb’s real victims. The horrific deaths in Nagasaki and Hiroshima receive short shrift.

Nolan might have done well to take a page out of the books of Jonathan Glazer’s Zone of Interest – for which Glazer took the Grand Prix prize at the Cannes Films Festival, or Felipe Galvez Haberle’s remarkable Spanish language debut The Settlers. Both NYFF selections are historical dramas of a sort that revisit what it means to confront the killing of a people. Glazer and Haberle push us to re-examine the history of war by shifting our gaze in oppositional but equally affecting ways.

Zone of Interest, drawn from a novel of the same name by Martin Amis, makes us squirm as we take in the domestic sphere of Rudolph Höss (Christian Friedel), commandant of the Auschwitz concentration camp. As we observe Höss’s wife (Sandra Hüller) and five children in an idyllic house adjacent to the camp, consumed respectively with the blossoming vegetable garden and playing in the bucolic fields, we take in the horror of what it means to hear gunshots in the distance. The question Glazer raises, of engaging in the banalities of living whilst committing genocide, is further amplified because of what he so deftly and uncomfortably implies about our own complicity as observers in other wars. What is not seen takes on seismic meaning well before Glazer cuts to the haunting final frames of real-life janitors cleaning the museum that now stands at the former camp site; the vitrines that encase shoes of the thousands of dead now scream bloody murder at us.

The Settlers similarly uses arresting imagery whilst playing with narrative convention to tell a story of the Selk’nam genocide in which the Ona natives of the Tierra Del Fuego archipelago were wiped out. Santiago-born director Haberle takes us to 1901 and the southernmost tip of the Americas where the unhewn and gorgeous landscapes make us feel like we are at the end of the earth, not the beginning of a century. Here a ruthless Chilean landowner hires a Scottish officer of the British Army (Mark Stanley) and a Texan mercenary (Benjamin Westfall) to establish a trade route for his livestock across the Atlantic, and instructs them to slaughter any indigenous people along the way. A mixed-race guide Segundo (Camilo Arancibia) is plucked off a chain gang to accompany them and this is the film’s wild card.

We sit with Segundo’s discomfiting experience as the lowest order of the power structure. We watch his enforced silences and the violence he perpetrates to save himself. Haberle’s characters, worthy of a John Ford movie turned on its head, form a revisionist history that is truer to the spirit of the oppressor and the oppressed, the colonizer and the colonized, than many epic war dramas. When the film shifts perspective in its final act and we move forward many years to reporters who find Segundo and record him as the last of a tribe, we already know him. We understand how posed images and crafted documents of historical record cannot grasp colonialism’s slaughters with the complexity they deserve, and we question all the history text books we may have read.

Scorsese’s Killers of the Flower Moon, the long-awaited Western drama starring Leonardo DiCaprio, Robert De Niro and Lily Gladstone, aims at something similar in the North American context. Set in 1920s Oklahoma, the meticulously researched big-budget film, based on the book by David Grann, is indeed a worthy epic. But where its retelling of murders of tribal members of the Osage Nation succeeds as storytelling, it somehow falls short of the truths that Zone of Interest and The Settlers approach in their final acts by drawing a through line from the exposition of a genocide to the inadequacy of its present-day vestiges.

The erasure of ancestry and bloodline summon ever more mystical questions about death that other NYFF selections probed. What rules govern some lives and not others, and what if we changed them? If death is not eternal, what does rebirth look like? Where does memory and legacy fit in all of this?

The films that tackled these questions stayed with me long past their running times and came from some of my favorite filmmakers.

Greek filmmaker Yorgos Lanthimos’ Poor Things is the rare film that is uproarious while being an intellectual exercise, thanks to a wonderful script adapted by Australian writer-producer Tony McNamara from Alasdair Gray’s novel of the same name. Lanthimos and McNamara are collaborators, who, as seen with their Oscar-winning film The Favourite, have long stewed in reinterpreting women’s subjugation and power. Poor Things is also Lanthimos’ take on Frankenstein and he leans into feminism and fantasy in a way that I bet would have tickled Mary Shelley. We meet a jerky young woman Bella (Emma Stone in her edgiest incarnation) and learn that her corpse has been reanimated by scientist Goodwin Baxter (an endearingly scalpel-wielding Willem Dafoe). Goodwin has performed this miracle by replacing Bella’s brain with that of a fetus. The zany energy of the film comes from the premise that Bella-reborn is a Victorian-era woman on the outside, with the mind of a guileless but brilliant child absorbing the world anew.

Free from the psychological rule book that her sex has learned to abide by, when Bella is romanced by the huckster Duncan Wedderburn (Mark Ruffulo, hilarious as a rakish dandy) she promptly sets out with her new lover on a voyage across the world. Bella is as an avid explorer as Columbus or Magellan but her big questions are void of predilections to capitalism, colonialism and especially, patriarchy. Why must she eat, dance, use money, exert power or have sex a certain way, Bella wants to know, earnest as a toddler with a puzzle. Stone, as the soul of the movie, makes the daunting task of playing a mash-up of woman-child-zombie-suffragette appear wildly graceful. The question at the movie’s core is iniquity and Poor Things has found a way to pose it that makes our rules appear as ludicrous to us as to this incarnation of Bella.

Reincarnation and possibilities after death are also at the core of French director Bertrand Bonello’s The Beast and Italian director Alice Rohrwacher’s La Chimera. Both romantic dramas have more than a touch of the magical about them, tilting to sci-fi in Bonello’s film and imbued with an ineffable dream-like quality in Rohrwacher’s.

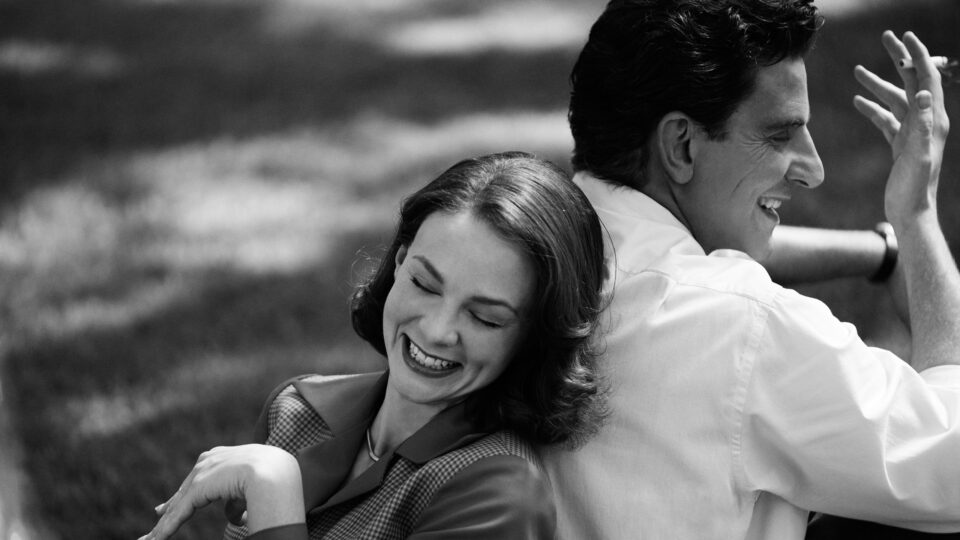

The Beast imagines the same couple reborn, unbeknownst to them, over three time periods. Gabrielle (Léa Seydoux) and Louis (George MacKay) shape shift through an illicit love affair in belle époque Paris, a predatory relationship between incel and aspiring actor in contemporary Los Angeles, and a future where both love and trauma can be erased. La Chimera centers on a former archeological scholar, Englishman Arthur (Josh O’Connor), who has just been released from prison and goes search of his dead love Beniamina in 1980s Tuscany. Arthur is driven to use his penchant for being able to sniff out buried Etruscan antiquities to rejoin his love in another world.

Both films require patience, but their directors are so skilled with their material, it feels inconsequential that we don’t know always know where we’re going. The Beast and La Chimera keeping us guessing to the very end when their wrenching but sublime aha moments allude to the wonder of a life lived, and lived again. Bonello and Rohrwacher expertly tease the notion that love is the real antiquity, a treasure that can live on.

The wonder of a life lived is explored in another NYFF selection, The Taste of Things. Not since 2014’s Cloud of Sils Maria have I seen the fantastic Juliette Binoche inhabit a role so entirely. As the title suggests, this is a movie about food and the way it inspires memory. Vietnamese filmmaker Tran Anh Hung, who won Best Director at Cannes for this sensuous film, casts Binoche as Eugénie, cook for two decades to renowned gourmet Dodin Bouffant (Benoît Magimel). In real life, the two actors were once partners and this might have something to do with their incredible on-screen chemistry. The pair make entire worlds pass in a glance as they prepare lavish meals in a rustic nineteenth century kitchen.

Under Hung’s direction, cinematographer Jonathan Ricquebourg’s camera caresses vegetables that are brought in from the garden and turned to silky broth in copper pots as large as bathtubs. He lingers as meats are made tender, and builds anticipation as pastries are baked to perfection. This is slow cooking and slow romance that takes a dramatic turn when Eugénie becomes ill and Dodin begins to cook for her. We are reminded that food can be decadent, but at its core it is sustenance, healing and life.

When Eugénie can no longer cook for Dodin, Dodin finds that his real quest is not in crafting and consuming the perfect meal but in finding someone who can conjure the precise flavours and textures of Eugénie’s cooking because that is where sense memory lies. Eugénie’s legacy is in the touch of her hand, the way she stirs a pot and knows just when an ingredient is enough. It is in the way her cooking evokes emotion and Hung is getting at what makes legacy most powerful; the ability to move others. Dondin’s savior is the gastronomic prodigy Pauline (Bonnie Chagneau-Ravoire), one of Eugénie’s assistants. A child of enormous potential and intuitive taste buds, Pauline can carry this legacy, making the The Taste of Things one of several NYFF selections that sees death make way for life through the prism of the next generation.

Numerous other films in the past year’s lineup are similarly concerned with inheritance. Michael Mann’s blockbuster Ferrari serves up Adam Driver as sports car magnate Enzo Ferrari, marked by the death of one son and preoccupied with bringing another into the fold. Ryusuke Hamaguchi’s Venice Film Festival Grand Jury Prize winner Evil Does Not Exist poses the question of humanity living symbiotically with nature by narrowing the focus to one small village and one child. Hayao Miyazaki’s latest animated fantasy The Boy and the Heron has taken both box office and critics by storm in a tale of a boy processing the death of his mother. The film is one of remarkable sensitivity, presenting complex issues of conflict and grief through the eyes of a child amongst a fleet of birds and beasts. Indeed, eighty-three-year-old Miyazaki came out of retirement to work on the film and has called it a way of saying goodbye to his grandson. Meanwhile, the documentary Ryuichi Sakamoto: Opus elegizes one of the great musician’s last performances as a tribute from son to father. The film features Sakamoto alone at his piano performing a carefully curated farewell set piece at a time when he was unable to travel to audiences as he battled cancer. Neo Sora (Sakamoto’s son) filmed in dramatic black and white emphasizing both the contrast of piano keys and of living and dying.

Sakamoto composed nearly fifty film scores in his lifetime and his last was for one of the year’s most haunting movies – Monster from another great Japanese artist, Hirokazu Kore-eda. Sakamoto died in 2023 weeks before the film’s release and Kore-eda fittingly dedicated his film, about the friendship between two young boys, (Soya Kurokawa as Minato and Hinata Hiiragi as Yori) to Sakamoto’s memory.

Monster’s script which was written by Yuji Sakamoto (no relation) was the screenplay winner at Cannes, and is a masterclass in shifting perspectives. A story which appears to be about classroom bullying is revealed to be about an entire society’s prejudices. The two boys’ friendship can only flourish in an abandoned tram car in the midst of a forest away from agitated parents and teachers. The unanswered question of the film is whether these boys can survive and thrive in an environment that opposes them for a multitude of reasons. Monster hints at the possibility that life can be so stacked against some that happiness only feels possible outside of its limits.

And what when people become so certain of this that death feels like their only choice? Even when death by suicide does occur in films, it is rarely the true subject of them. All too often when suicide is depicted in film, it exists to serve up melodrama or facilitate plot. We are too afraid or ashamed of the idea to spend two hours navigating its terrain. Cinema has the capacity to serve people who experience the agony of suicidal ideation, as well as the friends and family who want to help or feel unsupported in the aftermath. I was heartened to see two excellent films at the NYFF this year which made space to explore suicide and won plaudits for it; Cannes Palme D’Or winner Anatomy of a Fall from French director Justine Triet, co-written with her partner Arthur Harari, and All of Us Strangers, British director Andrew Haigh’s gorgeous film adapted from Taichi Yamada’s 1987 novel Strangers.

Anatomy of A Fall is exactly that. A journalist arrives at a mountain chalet near Grenoble to interview novelist Sandra Voyter (Sandra Hüller again in another excellent role). Her husband Samuel Maleski (Samuel Theis) is playing music so loudly in the attic that the pair abandon the interview. The disorientation that comes from this moment, of two women trying to converse amidst an onslaught of sound, remains with us throughout the film. Soon after, the couple’s son Daniel (Milo Machado Graner) returns from a walk with his guide dog to find his father’s dead body below the attic window. What ensues is part history of a marriage gone sour, told in flashback, and part courtroom thriller as Sandra is tried as a potential suspect. A bruise on Sandra’s arm suggestive of marital violence, combined with the prosecution’s claim that Sandra’s novel may foreshadow her ill intent further muddy the waters. Sandra’s friend Vincent (Swann Arlaud) acts as her conscience for us as we watch, their conversations providing an insight into Sandra’s state of mind.

As investigators try to work out the ‘anatomy’ of the title – whether Samuel fell by choice or force, we witness the ways a possible suicide can shake a family. We see the havoc a criminal investigation and a slew of memories and past incidents can wreak. In one key flashback Sandra and Samuel have a fight so messy it feels intrusive to watch them hurl insults and become aggressive. It is a moment many couples may recognize in themselves but be loath to admit. The film tackles the feelings that arise when a partner’s death casts blame over every past action. Triet allows us to see what the shape of keeping a family stable, while processing trauma, can take. Ultimately, she provides an exquisite look at how the grief of a father’s suicide threatens the bond between mother and young son, and shows us that healing can be found.

All of Us Strangers does its work by looking at both the root of suicide and the aftermath of death. English writer-director Andrew Haigh is a master at crafting deeply felt relationships and it’s easy to see why this film swept the BAFTA awards. All of Us Strangers had me from the first frame. Haigh’s landscape is a newly built, largely empty high rise on the outskirts of London. The building stands solitary and cool in its posh urbane modernity and pin-drop silent vistas from expansive windows. The setting echoes the plains of depression; vast, cut-off, melancholic and occasionally beautiful. Two occupants, possibly the building’s only two, Andrew Scott as Adam and Paul Mescal as Harry, appear to have picked this place as a refuge from the world, but their connection quickly supersedes the emotional scars they might be nursing.

Both these brilliant Irish actors are better known stateside for their heartthrob quotients – Scott was Fleabag’s ‘hot priest’ and Mescal Normal People’s Connell – but All of Us Strangers has you wondering that they could ever be anyone else. As Adam and Harry’s relationship builds, it is marked by an open sincerity that echoes the film’s eighties pop soundtrack – songs which we won’t admit make us want to sing and cry. Still, my packed theater was sniffling in unison as elbows rubbed.

As the men reveal themselves to each other and to us, we learn that Adam, who is some years older than Harry, is in the process of writing a screenplay, one that resurfaces his childhood. He repeatedly visits a couple – played by Jamie Bell and Claire Foy, in his childhood home. The early-middle-aged couple appear to be Adam’s parents from when he was young and are around his age now. Over several of these encounters, Adam starts treading over the past with the couple, particularly their challenges accepting him as a young gay boy.

These actors are so skilled that we suspend disbelief about what these ‘visits’ are – time travel, imagination, or the supernatural – and become wholly invested in a person grappling with unresolved pain and the sorrow of all the things he can no longer say to the people he lost. As these visits punctuate Adam and Harry’s relationship, we learn more about the quieter Harry who holds his own pain closer. Stray comments give us a glimpse into Harry’s loneliness and his own struggle to be accepted by a family who he appears estranged from. Harry is the rock who helps Adam through the grief over his parents, but where the film shines is in revealing the fragility that lingers beneath the younger man. It is an astonishing portrait of depression, lyrically but insistently reminding us that the blackness can be quiet enough to steal a person while we’re watching.

Soleil Nathwani is a New York-based Culture Writer and Film Critic. A former Film Executive and Hedge Fund COO, Soleil hails from London and Mumbai. Twitter: @soleilnathwani