Pop Stuff: Killing Your Darlings

As we apply the contemporary to history, should we separate the artist from the art?

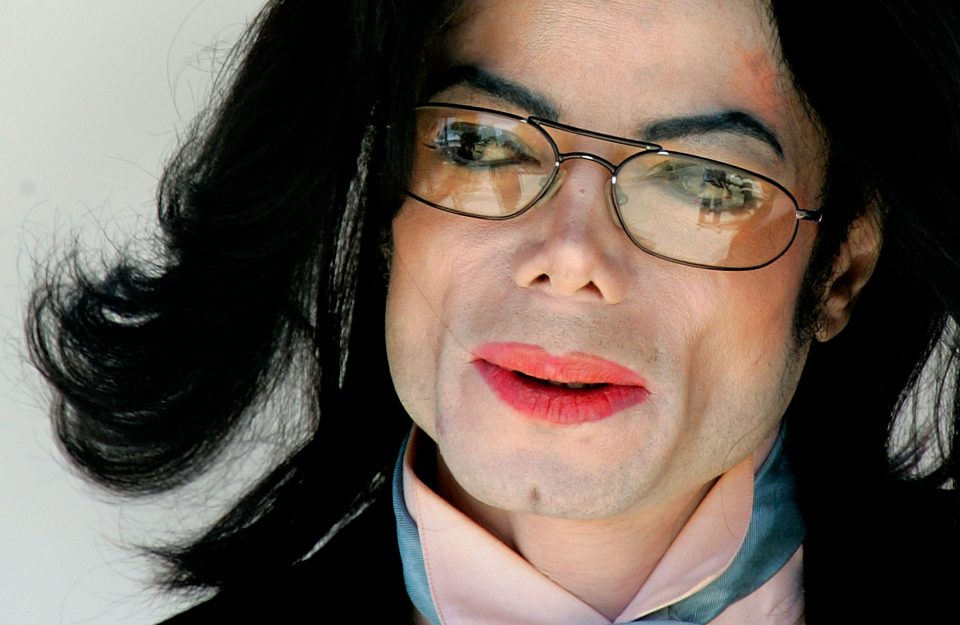

Michael Jackson's accusers are making their trauma public in an environment that is overdue to accept it. Photo: Carlo Allegri/Getty Images

In the Summer of 1988 Michael Jackson performed at Wembley Stadium as part of his BAD tour and Britain and much of the world caught Jackson fever. His music, more than any other artist’s, was the soundtrack to my childhood. Each song had the power, years later, to recall a memory, unearth a secret, dip me in a wave of nostalgia, the kind of thing that happens when you revisit a secret nook in a childhood playground. Cloaked in my pop diva avatar, I danced furiously in fingerless gloves to “Billie Jean” and grew emboldened every time “Wanna Be Startin’ Somethin’” came on the radio, as priceless feelings for a gawky adolescent trying to find an alternate reality. At the end of the concert, Jackson came on stage for an encore and sang “Man in the Mirror.” It was the song he most loved in his canon and giving it his all under a single spotlight, the man and the moment seemed ethereal. He was every bit my idol.

Years later in the aftermath of the Weinstein allegations, artistic heroes are coming undone as victims’ voices are heard and the protective gloss of celebrity and power proves no match to a wave of empowerment fueled by fourth wave feminism. Upon the conviction of Bill Cosby, who in repellently robbing women of their dignity, also robbed much of a nation of their TV dad, I found myself scrolling through Jackson’s Wikipedia page, revisiting the question of whether he had abused minors, whether his anthems were tainted, whether a trip down memory lane through his music was forever stained.

Even with the recent release of the HBO documentary Leaving Neverland which presents extensive and heartbreaking interviews with two of his accusers, we might never have absolute certainty, but we would be remiss to hide from the questions hanging heavy on our icons. Our memories feel a paltry price to pay for those who have been cheated of theirs. Jackson was acquitted before he died. His accusers, like so many others who have recently told their stories, are making their trauma public in an environment that is overdue to accept it. As much as I’d like to moonwalk back to brighter days, I can’t. As the line between the art and the artist is finally being redrawn, the uneasy shift is a new hope for art to serve its highest purpose; to open us up.

For centuries, great artists have been forgiven indiscretions and abuses. Much of this is because contemporary norms don’t apply to history. Paul Gaugin, a virtuoso whose paintings are the crown jewel of museums across the world, was also a pedophile and domestic abuser who left his wife and children and took several child brides in Tahiti. His young muses revived his output and he received no public censure. Even as norms changed from Gaugin’s 19th century days, our reverence for creative genius persisted in us elevating the art and turning a blind eye to all manner of atrocities committed by the artist. The comedian Hannah Gadsby reminds us of this in her brilliant stand up piece Nannette where she argues that for all of Picasso’s cubist perspectives defining him as the most revered painter of the 20th century, not one reflected a woman’s. She describes cubism as “putting a kaleidoscope filter on your dick.”

In fact, Picasso regarded the women he was with as “machines for suffering.” He took artistic pride in extracting everything he could out of them and throwing it into his work, commenting that his oeuvre could be divided into seven distinct styles – one for each woman. Picasso’s granddaughter Marina said of his relationships in her memoir, “he submitted them to his animal sexuality, once they were bled dry, he would dispose of them.” In 2010, Picasso’s Nude, Green Leaves and a Bust was auctioned off for $106.5 million dollars, breaking the then world record for a piece of art. It was a deconstructed image of his lover Marie Therese Walter, who was only seventeen when they met. She died by suicide while he died a legend.

We exalt Picasso’s work, barely considering its root claiming history as a justification for tolerance. But as we begin to grapple with the work of our contemporary artists, the history of the nude might be reconsidered as the history of toxic masculinity, a precursor to the male gaze of directors. You could draw a line from these great painters to the actions of auteur directors Bernardo Bertolucci and Roman Polanski. Over a decade ago, Maria Schneider, the actress in Bertolucci’s Oscar winning film Last Tango in Paris, revealed the abhorrent details of a rape scene in the film where butter was used as a lubricant without her knowledge because as Bertolucci put it, “I wanted her reaction as a girl, not as an actress, I wanted her to feel humiliated.” Bertolucci, who died two years ago, retained his Oscar for the film. Polanski, who was convicted of the statutory rape of a thirteen-year old in 1978, causing him to flee L.A for Paris, was subsequently awarded an Oscar in 2003.

In the aftermath of #MeToo and a torrent of victim testimony that has been too vast and too public to ignore, artists are finally being held accountable for their actions by the institutions that supported them. Polanski’s Oscar was revoked last year. Harvey Weinstein faces his first trial for rape allegations in May. R. Kelly’s label RCA Records dropped the singer after protests and pressure from the airing of a TV docuseries detailing his abuse of women. Kevin Spacey minimizing allegations from young men he mistreated by using them as his coming out moment was not enough to keep him employed by Netflix. Louis C.K.’s comedic skits about masturbating in front of young women no longer have a stage. Amazon is trying to break their contract with Woody Allen, the director that once was a coup for them, in light of renewed focus on his adopted daughter Dylan Farrow’s testimony that he abused her.

Even as institutions draw a harder line, the long overdue intolerance for abuse, misogyny and marginalization is replete with challenges. Sentencing someone to creative jail without proof of their guilt is a dangerous precedent. Saying that a perpetrator amongst us today can no longer rely on the system to distribute their work begs the question of what we do with the work of those who have passed. Denying an artist space to shine is denying all those who worked with them. Condemning an artist for a transgression by silencing their art extinguishes the muse that inspired them and suggests that the artist cannot evolve. Blindly rejecting an artist who is an abuser buries a crucial dialogue around the fact that almost all abusers have been abused.

The hard line only preserves art that shares a foundation with our ever shifting principles. Do we turn to burn all the Picassos and with them the evolution of an art form? Do we switch off Woody Allen, and in turn Diane Keaton, without proof of his guilt? Do we cancel R. Kelly and by doing so his collaborators? Do we assume that the self-awareness and humanity of Godard’s cinema at 88, didn’t evolve from the narcissism and misogyny evident at 28? Does the King of Pop deserve his crown?

The system is cracking and each fissure poses a question without an easy answer. The backlash to Spotify’s decision last year to drop R. Kelly’s music from the streaming platform is representative of the complex nature of playing morality police. Spotify made the decision amidst renewed outcry over R. Kelly’s years of allegations of sexual misconduct, misconduct that was recently explored in the docuseries Surviving R. Kelly, providing horrifying testimony of what appears to be an underage sex cult. Following the docuseries, the police opened a criminal investigation into the erstwhile “Pied Piper of R&B” and several artists from Chance the Rapper to Lady Gaga pulled their collaborations with him. And yet, when Spotify dropped R. Kelly, the music industry and the fans reacted swiftly, pointing out the dangerous nature of playing adjudicator and the myriad other artists on the platform that had allegations against them. Eventually, Spotify let the power rest in the hands of the audience, giving users the ability to block an artist from appearing in their playlists.

At a murky but critical time, Spotify’s decision points to the crux of navigating the problem. The audience. You and me. In the vast majority of allegations post Weinstein’s fall from grace, the transgressions were rumored, widely known, or even documented in the press decades before those in power finally took action. The systems didn’t cave because corporations grew a moral conscience overnight, they caved because as a society we evolved to the point where we wouldn’t be quiet if they didn’t. The collective outrage has been driving the hand of commerce that gave the artist a platform, to take it away. If artists who are morally bankrupt know that they will suffer consequences, we actually stand a chance of voiding a social contract that has granted that misbehavior is a fair trade for genius.

In doing so, our artistic canon isn’t being diminished, it’s being enhanced. Movie studios aren’t destroying film reels but they are enforcing codes of conduct and hiring under represented film makers at unprecedented rates. Jay-Z’s streaming service Tidal has followed Spotify’s lead, allowing users to block artists. Just last month, New York’s Museum of Modern Art, which gained international prominence for its now famed Picasso exhibit, announced that they would soon close for four months to rehang the entire collection and rethink the way art is presented to the public, showing lesser seen artists from diverse backgrounds to reflect the nature of society itself.

The hope is that we are in the opening act of a seismic shift in the way we create, consume and reflect on art. The catch is that the onus is on us to see it through. It’s a tall order. At a time when politics feels like it weighs heavier than ever, it’s challenging to see art as political. Getting lost in a painting, buying movie tickets or throwing on headphones should not feel like an act of resistance. But finding an ethical way to consume art is confounding and exhausting. It’s not like opting for the free range chicken on the menu because it’s tied up in our emotions. Even so, changing the way we bear witness is the only thing that ensures change in a system that knows that the public will be quicker to protest the absolution of genius than to protect it.

It’s difficult not to want to cling to the things we love but reassessing the artist doesn’t mean discarding the art. By viewing it through a more honest lens, we have a more nuanced view of the past, the process and the thing itself. By insistently allowing for the voices of the victims, we find new voices within the work and new compassion within ourselves. In revisiting famed French sculptor Rodin, we might learn more about Camille Claudel whose young hands shaped much of his work. In switching on Bill Cosby, we might find heroes in the women that spoke truth to his power. Pausing before we hit play brings us back to the root of what art is, not a static escape but something dynamic that exalts or repulses us as it changes us. Today, the memory of Jackson singing “Man in the Mirror” makes me wonder if it was his concert favorite because in calling us to be our best selves, he hid his demons in plain sight. I’m not looking forward to diving into Finding Neverland, but a reckoning feels long overdue. We only elevate the system that fosters creativity by being willing to kill our darlings.

Soleil Nathwani is a New York-based Culture Writer and Film Critic. A former Film Executive and Hedge Fund COO, Soleil hails from London and Mumbai. Twitter: @soleilnathwani