Report: HCL Concerts’ San Francisco Sojourn with Amjad Ali Khan and Amaan and Ayaan Ali Bangash

The sarod maestro and his sons performed separately and together at what is likely the first of many international shows hosted by the Indian tech giant

(From left) Amaan Ali Bangash, Amjad Ali Khan and Ayaan Ali Khan at HCL Concerts' San Francisco edition on December 9th, 2019. Photo: Courtesy of HCL Concerts

A week after the performance in frigid (but welcoming) New York City (at the hallowed Carnegie Hall, no less) sarod and Indian classical music legend Ustad Amjad Ali Khan found himself in San Francisco performing at a much smaller United Club, playing to about 300 people.

It was the third international edition of HCL Concerts, which have been a mainstay in different parts of India since 1998, as a means to bring music lovers together, plus as a treat to their employees, clients and customers. Over at San Francisco, they were testing the waters at a small club housed within the massive Levi’s Stadium, which usually hosts National Football League matches.

Dressed in suitably formal (and Indian formal) attire, the technology company’s clients were treated to Khan and his sons performing for over two hours. Whether it was jugalbandis or Rabindranath Tagore compositions or arrangements in raag desh, malkauns and rageshri, the trio’s separate and collective performances were picked out to showcase perhaps the more globally accessible sides of Indian classical music. As Amaan Ali Bangash mentioned at the start of an interview held a few hours before the performance, they only consider themselves as messengers and vessels of music. If that means changing their own form “so that it goes through to the audience,” he’s more than happy to do it.

Ayaan adds, “When you’re on stage, you have to be a performer, you’re not there to educate people. You’re there at the end of the day to owe them something, because they’ve bought a ticket.”

Even as HCL Concerts has just announced a debut Bengaluru edition, the executive team mentioned that they are looking at more global capitals to bring fusion, Indian classical and folk performances. Perhaps, they may even aim for New York’s Madison Square Garden, depending on how they scale-up. As for Khan and Amaan and Ayaan, they spoke about traveling and performing together, their upcoming collaboration with the likes of Eagles guitarist Joe Walsh and Grammy-winning artist Sharon Isbin. Excerpts:

How was your New York concert?

Ustad Amjad Ali Khan: Carnegie Hall was the first one. Thanks to HCL, it’s the first corporate house that’s professionally, with conviction and steadfastness presented a classical concert like that. Everything depends on how you present and where you perform. First, there were kings who would patronize classical music, now there’s corporate houses.

Amaan Ali Bangash: It was a good concert and it’s presented in such a nice way, Indian classical music. We had a warm house and a lot of people there. It was received very well. You feel very blessed that you get to play in Carnegie Hall, one of the world’s best venues.

Ayaan Ali Bangash: There’s a joke that when someone asked, ‘How do you get to Carnegie Hall?’ the reply was, ‘Practice, practice, practice.’ (Laughs) But we’re very fortunate that because of my father we get to perform at all these beautiful venues around the world. Amaan bhai and I have played there a few times.

Khan: The venue for music matters a lot in the western world. In our country, they seat us down and ask us to play anywhere. One organizer had asked us to perform by a water bank and we didn’t ask about it beforehand and just knew all our requirements were in place and took the gig. There was so much sound of the water hitting the shore, that you can’t hear the sarod only.

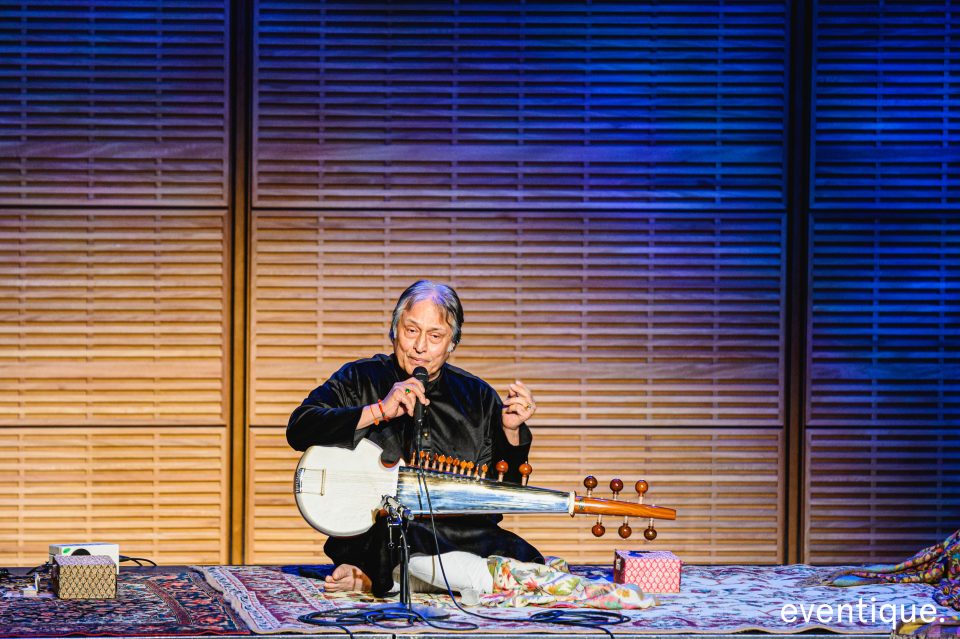

Ustad Amjad Ali Khan live at Carnegie Hall, New York City as part of HCL Concerts. Photo: Eventique

Is it a very 21st Century concern for Indian classical artists to think about engaging with their audience?

Amaan: In the 1920s, when there were Rajas, you had to think about the Raja not beheading you for playing bad music. Today you have to think about the audience not getting up and walking out. We as musicians are a tool – we don’t produce music, it comes through us and goes through to the audience. You have to keep changing yourself so that it goes through the audience.

Ayaan: When you’re on stage, you have to be a performer, you’re not there to educate people. You’re there at the end of the day to owe them something, because they’ve bought a ticket.

Khan: I tell many younger classical musicians, we’re born in this world to provide happiness, not worries. There are worries when you never finish your raags – that’s a national tragedy, that someone is just looking at their watch and wondering when you’ll finish your performance. This sense of proportion is so important in every field. Otherwise why would we talk about it? It’s all about conciseness, preciseness, that lacks in our system.

Amaan: The packaging has to change as per the audiences’ likes and dislikes.

Tell me about the all-night concerts you’ve performed. Does it still happen even now?

Amaan: That still happens – when he (Khan) plays in Calcutta or Poona – my father will play for three hours also, because he’s been asked to play for three hours. In those three hours, his presentation will be different, as is the case for any of us. But when you’re given a slot of one hour, the presentation has to be different. Playing in a college is different than playing at Sawai Gandharva in Poona. It’s different music. When that 10 o’ clock ban came in, I think that changed some things for Indian classical music performances.

Khan: The time was different and the era was different too. I was called to a festival by a zamindar, and it was 11 pm and I was offered tea. I thought it was time to go to sleep but I was told he’s only awoken now, and he sleeps in the day. The all-night concerts that happened today, I’m not in favor of those. I’ve played all alone through the night, I was 25 years old at the time and I played from 9 pm to 7 am once, in Calcutta. It was a ticketed show, house full.

There’s one instance where all three of us have performed through the night. Bengal could absorb, they have so much capacity. It happened, but it happened once in a while. The first time an audience sees and hears us, we want them to come back a second time too. That’s a challenge right now.

When you perform with your sons, is it in the capacity of a guru, a parent and as a fellow musician. Which one are you first? And do they surprise you enough on stage?

Khan: We’re all solo musicians, we all get called for solo performances, and these two get called for duet performances too.

Amaan: Quite often we get called for duet performances only (laughs).

Khan: Then there’s times when all three of us perform, which happens especially for international concerts. To show the public the connect – the bonds seem to be breaking these days. The children are detached from parents, or parents are detached from their children. I don’t travel without these two, actually. I don’t travel alone because I’m afraid. It’s a great joy when we play together.

Amaan: So do you play as a guru, father or fellow musician? The last one definitely not I’m sure (laughs).

Khan: Basically, we’re friends.

Amaan: They (points to Ayaan) have more conflicts

Ayaan: We all have our share of conflicts, but he (Amaan) is someone who makes peace very quickly.

Amaan: I’ve learned one thing from him (Amjad) – that everyone is here for a very short period of time, so let’s have fun, let’s love everybody but why have anything as anyone? I always feel I’m a very average student – because of that feeling, it keeps me going with my riyaaz.

Khan: Our gurus teach us to look at our weaknesses first. Our human nature, however, often leads us to look at the bad in others. Gharane ke upar ladayi hota hai, there’s a lot of rivalry. I always admire Tagore because he made his songs and poetry based on classical raags, but always added an additional note in the raag. I didn’t like it at all first, Rabindra Sangeet, then when I performed with a great Bengali singer named Suchitra Mitra – we have an album called Tribute to Tagore – it became very appealing. His music and literature was outstanding. Only a genius can take liberties. Mediocre people just follow in line.

What can you tell me about your collaboration with Joe Walsh?

Amaan: We just recorded a whole album with Joe Walsh.

Khan: And also with Sharon Isbin, we all played one piece each on her new album. It’s called Strings for Peace. The interesting thing is that God has made the seven notes that we call Sa Re Ga Ma, while the West calls it Do Re Mi Fa. The sound is the same. It’s like a flower, which can be used for all occasions, whether it’s death or celebration or whatever else. People fight over whether to call something a devotional song or not, but it’s using the same seven notes.

Ayaan: We finished the recording in two sessions. He’s been a great admirer of the sarod and when he was in Bombay he reached out to us and now owns a sarod. Amaan and I sat with him through the day and he kind of picked it up, whatever little bit we did. The first session of the recording happened when we reached L.A. from Vancouver, from a festival. Our sarods didn’t arrive in time.

Khan: All three sarods didn’t turn up!

Amaan: It went off somewhere else.

Ayaan: So the sarod we’d given him in Bombay came to the rescue, which was actually made by the same maker who does ours.

Khan: We recorded at this studio in Beverly Hills. The second time we went, though, we had our own sarods.

Amaan: It should come out by February. He’s a great musician, his whole team as well. They’re not show-offs. The problem with our musicians sometimes is, when they see you in the green room, they’re looking at you and performing, they’re trying to prove a point. Over there, they’re so subtle, you don’t know if he’s going to play or if he’s even a musician until he holds an instrument. They respect each other so much and that’s something we need to learn from them.

Khan: We even met the famous drummer of the Beatles, Ringo Starr. He was also there. He’s 79! I couldn’t tell. The way he plays drums, it feels like a god-given gift. I was singing something and he gave a beat, I was shocked. He was just playing on the table, that’s it.

Ayaan: Ringo is Joe Walsh’s brother-in-law. We just met after one of the sessions.

Amaan: Ringo has got the energy of a 25-year-old.

Your father performed “Journeyman” on your album Infinity, which you worked on with Karsh Kale. What was that like?

Ayaan: I think it was the first time people were hearing my father in that light. I don’t think he’s ever played in this electronic space. The sarod’s tone is extremely different. We thought it was something interesting that we could get our father to do and he was very sporting.

Khan: It’s about communication through music. Our trio show, in Russia with the Moscow Symphony Orchestra. Nirmala Sitharaman was in the audience too. Russia might be viewed as one whose government rules with an iron fist, but in their music tradition, they’re so different. They’re such gifted artists. If you look at the good in everything, then you can communicate more easily. People say so much about our music and things like ‘Fusion is confusion.’ Some fusion is not good and appealing, not everyone can do it.

Amaan: It’s not an easy thing to do.

What else is coming up through 2020?

Ayaan: There’s this album with Sharon, Strings for Peace, coming up as well. She’s one of the finest classical musicians. She’s got an American music honor that’s come to a guitarist after 57 years or so. We’re playing with the Chicago Philharmonic in April. Whole lot of things lined up. Every day is a new day.

Khan: That’s a new kind of fusion too – when you write for and with an orchestra. They’re so brilliant.