Sinead O’Connor: 10 Essential Songs

The Irish star, who has died at age 56, sang with power and grace

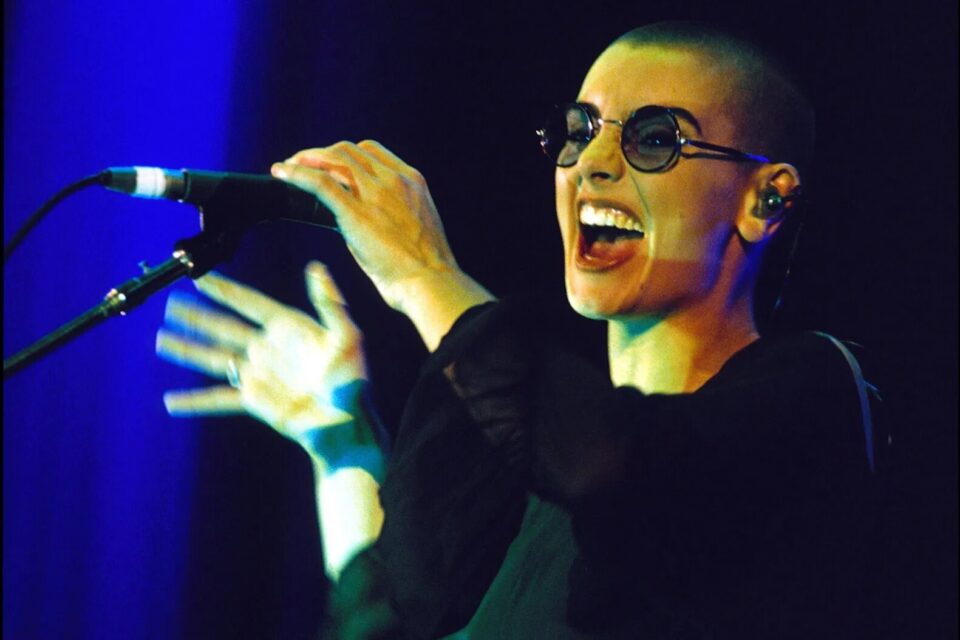

Sinead O'Connor in 1990, the year she became a global superstar. ALAIN BENAINOUS/GAMMA-RAPHO/GETTY IMAGES

Sonead O’Connor burned fast and bright from the very start. “I think I’m probably living proof of the danger of not expressing your feelings,” she told Rolling Stone‘s Mikal Gilmore in 1990 — the year that her second album, I Do Not Want What I Haven’t Got, turned the Irish singer with the unforgettable voice into an international superstar. The songs she recorded back then still sound as vital as they ever did, and maybe even more so, as the world mourns her too-young death at age 56; anyone who explores her catalog will find inspiring performances that go well beyond the hits. “For years I couldn’t express how I felt,” she continued in the same interview. “I think that’s how music helped me. I also think that’s why it’s the most powerful medium: because it expresses for other people feelings that they can’t express but that need to be expressed. If you don’t express those feelings — whether they’re aggressive or loving or whatever — they will blow you up one day.”

Hear this playlist on Spotify.

‘Nothing Compares 2 U’ (1990)

“As far as I’m concerned, it’s my song,” O’Connor once said — and she was right. “Nothing Compares 2 U” may be the only time a singer out-performed Prince on one of his own songs, with O’Connor funneling a lifetime’s worth of anguish into one of the greatest heartbreak ballads ever recorded. With its mix of whispery subtlety and swooping flourishes, her cover was the greatest Gaelic blue-eyed soul performance since Van Morrison: a song big enough to make — and overly define — a career. It also came with an astonishing video, where O’Connor managed real tears by thinking of her tragic relationship with her mother, as the camera zoomed tight on her face, framed against a black void. —B.H.

‘Drink Before the War’ (1987)

O’Connor was 15 and full of teenage angst when she wrote this eviscerating dirge about a man — the headmaster of her Catholic school, it turns out — determined to smother creativity. Fifteen years later, in an interview with rock critic Steve Morse, the singer said she could no longer relate to the song, which appeared on her 1987 debut, The Lion and the Cobra. “I hate ’Drink Before the War,’” she said. “It makes me cringe.” Even so, fans continued to connect with the vulnerable defiance of the lyrics. “Well, you tell us that we’re wrong/And you tell us not to sing our song,” O’Connor whispered before the song built toward a cathartic purging. Said O’Connor: “It’s like reading my diary.” —J.H.

‘Mandinka’ (1987)

The shaved head that greeted record buyers on the cover of The Lion and the Cobra instantly set O’Connor apart. But “Mandinka” made it clear that everything about her was about to rewrite the rules of pop. Corrosive guitars and a title inspired by a West African people of the same name weren’t supposed to sit side by side on a pop record in the Eighties, and nothing at the time sounded like the banshee wail that she unleashed on the chorus. Far more than her image, the steely edge in her voice on “Mandinka” announced the arrival of an artist who would be among rock’s most uncompromising. —D.B.

‘The Emperor’s New Clothes’ (1990)

This standout from I Do Not Want What I Haven’t Got sounds upbeat — even jangly. But the subject matter isn’t exactly bright. It’s a pointed, detailed missive seemingly addressed to a former lover, as well the masses who kept judging O’Connor — the “millions of people/To offer advice and say how I should be,” as she puts it in the song. (She would later claim those shots in the lyrics were actually aimed at U2.) O’Connor was a newly single mother at the time, and the song takes note of “how a pregnancy can change you,” before ending with a steely statement of purpose: “I will live by my own policies/I will sleep with a clear conscience/I will sleep in peace.”

‘Black Boys on Mopeds’ (1990)

O’Connor said she wrote this haunting ballad after two teenage boys, riding borrowed mopeds that police assumed they’d stolen, were chased by law enforcement and fatally crashed. The song, as O’Connor wryly noted in a performance decades later, “wouldn’t make you want to live in England, basically.” “Black Boys on Mopeds” stands as one of the singer-songwriter’s most profound, piercing statements, one that’s gained new relevance with covers from Sharon Van Etten, Phoebe Bridgers, and singer-songwriter Shea Rose in recent years, as Black Lives Matter uprisings have brought increased awareness to the very type of police killings O’Connor wrote about more than three decades ago. —J.A.B.

‘I Am Stretched on Your Grave’ (1990)

Reciting a traditional Irish poem about a morbid love affair over a “Funky Drummer” loop, O’Connor brought all her otherworldly vocal power to bear on “I Am Stretched on Your Grave” — and wound up with a performance that transcends its very early-Nineties production to land somewhere near timeless. Who else could sing lines like “My apple tree, my brightness, it’s time we were together” and make them sound this urgent? It says something that she sang this verse from the 1600s with the same intensity and presence that she brought to any of her other hits. In her final years, it was a highlight of her concerts, where she often delivered it in a spellbinding a cappella arrangement; in 2012, she dedicated it to Whitney Houston just weeks after the singer’s death. —S.V.L.

‘The Last Day of Our Acquaintance’ (1990)

Moving from gentle strumming and a sotto-voce delivery that draws in listeners in from the instant she begins singing to a big-rock explosion of guitar, percussion, and powerhouse vocals, “The Last Day of Our Acquaintance” is arguably the most emotionally devastating song on O’Connor’s second album. Released the year before she divorced her first husband, producer John Reynolds — who plays on the song and collaborated with her throughout her career — it’s a story about the end of a relationship. These two soon-to-be exes will “meet later in somebody’s office,” but, she sings, “you won’t listen to me.” Play the song, though, and that won’t be a problem — her honesty, defiance, and purity of voice turn the hurt of what’s ending into a mind-blowing affirmation of breaking free and moving on. —S.P.

‘All Apologies’ (1994)

It felt like everyone was mourning Kurt Cobain in 1994, including his own heroes like Neil Young — who dedicated his album Sleeps With Angels to Cobain — and Patti Smith, who would later cover “Smells Like Teen Spirit.” But O’Connor turned in one of the most moving tributes when she sang a gut-wrenching “All Apologies” just months after his death. Her rendition is even more stripped-down than the original, with her impossibly delicate vocals carrying the emotional weight of lines like “Find my nest of salt/Everything is my fault.” The cover, released on 1994’s Universal Mother, is easily overshadowed by her most famous rendition of another artist’s song. But following O’Connor’s death, it resonates more than ever. —A.M.

‘Thank You for Hearing Me’ (1994)

Reportedly inspired by her brief relationship with Peter Gabriel, the climactic song on one of O’Connor’s best albums, Universal Mother, may be the most amicable breakup song ever. Each verse repeats the same line — “Thank you for seeing me” and “Thank you for staying with me” among them — which alone gives the song the feel of a hymnal. Combine that with Sinéad’s tranquil delivery, and the mood is reflective and mature: a breakup song with no hard feelings and plenty of appreciation for what was. —D.B.

‘No Man’s Woman’ (2000)

O’Connor was no stranger to getting riled up, especially over feelings of being repressed. In this track from 2000’s Faith and Courage, she gets right to the point: “I’ve other work I want to get done/I haven’t traveled this far to become/No man’s woman.” But from its starkly beautiful hip-hop clip to its open-hearted chorus, “No Man’s Woman” is anything but a riot act; here, she transcends her turmoil and again finds beauty and release in her music. —D.B.

From Rolling Stone US.