Lou Majaw: ‘Still Surviving’

The 68-year-old troubadour from

Shillong has been making music for five decades, and damned if he going to show any signs of slowing down

Lou Majaw at a gig. Photo: Arjun Sen

When I arrived at Shillong’s U Soso Tham Auditorium that moist April morning, the jacaranda tree outside was in full bloom, its vivid purple canopy contrasting starkly with the performance hall’s unremarkable architecture. It was a sight that repeats often in the North-Eastern hill town””nature’s splendour sitting incongruously amid man’s repugnant creations. Shillong is a mostly unattractively and impractically designed city, more assembled than arranged. But the Khasi, Garo and Jaintia hills that engulf Meghalaya make up for the state’s architectural deficits. Forests, trails, rivers and lakes””most notably the enormous Umiam Lake, the 220 square-km man-made water body better known by its colloquial appellation, Barapani””are a quick escape from the city’s often-traffic-choked streets. But Shillong’s real vibrancy is prevalent in the musicality of its people. It’s often said, more true than apocryphal, that every other person in Meghalaya’s capital can play guitar. Equally true is that their repertoire likely contains at least a few Bob Dylan songs.

If there’s one man there who knows more than just a few Dylan tunes, it’s Lou Majaw. The irrepressible Khasi troubadour has, for the past 44 years, hosted an annual Bob Dylan celebration which coincides with the folk-rock legend’s birthday. The concerts have featured performances by innumerable songsters, both emerging and established. Amateurs are known to randomly jump in and offer their take of one of the master’s classics. The mandate is clear and rigid: you’re only allowed to play songs by Dylan or those of your own. No other music is allowed and absolutely no one is allowed to deviate from the rule. If you do, you will be shut down, as happened at last year’s celebration to an unfortunate singer who got carried away in the spirit of the jam and pulled out a jazz standard. Lou stormed the stage and stopped the performance mid-song. The miffed crooner was placated afterwards, but there was no calming the irate silver-maned Khasi man in that blasphemous moment.

Lou is referred to by many adjectives: a character, an institution, the Bob Dylan of India. The first two are apt””he is indeed both those things. As for the third description, I prefer to refer to him the one and only Lou Majaw. Almost anyone who has met him would agree, including day trippers from Guwahati and other nearby towns who are known to accost him in the street (he’s often seen striding through the town; he walks almost everywhere he goes), demanding selfies and handshakes with Shillong’s most recognizable resident.

When I entered the auditorium, Lou was going full throttle onstage in preparation for the next day’s concert. He was in his trademark getup: sneakers, mismatched socks, tiny denim shorts revealing a pair of muscular legs and wide black leather wristbands, his long, gray tresses cascading behind over a sleeveless T-shirt. On the stage with him were longtime collaborators: Arjun ”˜AJ’ Sen on electric guitar, Sam Shullai on drums and Ferdie Dkhar on bass, as well as a relatively recent one””Mark Williams, who handled percussion duties after setting up the P.A. system.

I had been invited, along with the singers Vasundhara Vidalur, Sonia Saigal and Rahul Guha Roy, to join Lou on a few of his songs at the release of his newest work, The Road Ahead. The album release was overshadowed by a more significant milestone””the concert was also the commemoration of Lou’s 50 years in music. The 68-year-old had been at it for five decades and damned if he was showing any signs of slowing down. Even in his last rehearsal, he was going at it as if he were in the middle of a concert performance. The next day, I sang a song along with Lou that carries as much Dylan’s imprint on his music as it is reflective of Lou’s very own ethos. From “Ain’t Got Nothing,” written in 1966:

Ain’t got no flashy suit / Ain’t got no shiny boots

Ain’t got nothing at all / Ain’t got nothing at all, nothing

Ain’t got nothing to lose / Ain’t got nothing to choose

Ain’t got nothing at all / Ain’t

got nothing at all, nothing

I had first met Lou about 25 years ago in Calcutta. He was with the seminal blues-rock outfit The Great Society then and I with my first band, Rock Machine. I don’t remember much about that encounter-there were a number of other bands at the festival and inevitably the usual distractions and excesses, so the memory is a bit clouded. Our paths didn’t cross again until 2012, when he invited my acoustic trio Whirling Kalapas to play at his Dylan celebration that year. This time the impression was more impactful. I was struck by his sheer vitality and seemingly indefatigable energy, and found myself regretting we hadn’t reconnected earlier. It struck me that even though he had been on the scene for far longer than me I knew very little about Lou. But just a few brief conversations in, I got glimpses of a man who had lived a pretty darn interesting life. Musicians love to imagine their lives as epic tales of bohemian deliverance; very few experience even a fraction of that. Lou is not one of them.

I got my opportunity to make up for lost ground three years later when Lou invited me to sing at his commemorative concert. When Lou came by my hotel room to chat about the gig, I got a few insights into his early life: he studied in an orphanage, worked as a farmer, had a bunch of kids scattered loosely around the North-East. He tossed an informational nugget or two as a throwaway, which piqued my interest further. I got a sense of a man who had lived life very much on his own terms. And I don’t mean that in the way it’s uttered these days””semi-mavericks becoming entrepreneurial successes after disregarding their fathers’ diktats to become computer engineers or financial analysts. Lou’s terms seemed to be different from everyone else’s. The answers lay in his past. I was keen to know more and so a few months later, I went back for a bit of a chitchat.

Lou is a curious mix of elements. He refers to himself in the third person (“Lou Majaw loves life!”) but is not egotistical. He is discarding of nostalgia and very self-effacing, but given the right nudge, loves to talk about himself and the experiences he’s had. He is kind and extremely generous but rubbed the wrong way (as with the singer who deviated from the Dylan-only mandate), he can be merciless. But he also forgives as soon as the moment has passed. He is unique and undeniable and is the sum of all his journeys””many of which have taken some very radical turns.

“We never knew what breakfast was. Or lunch or dinner. We just knew what a meal was.”

Lou was born in a small Meghalaya village in 1947 in abject poverty: “We never knew what breakfast was. Or lunch or dinner. We just knew what a meal was.” His mother had married at 16. She was uneducated and did odd jobs to survive. His father, a hunter, was poisoned one day by a close friend of his and died when Lou was just two months old. Lou’s birth had been preceded by two other boys, one of whom died a few months after Lou arrived. The surviving brother and he remained extremely close until he died sometime in the Eighties. (Characteristically, Lou can’t remember even the year, let alone the date””it seems to be a survival mechanism of the seemingly ageless musician.) When Lou’s father was gone, his mother remarried””not for love, he says, but out of a need to find her way out of poverty. She proceeded to have five sons and five daughters from her second union.

When Lou was of school-going age, he was put into a missionary- run boarding school in Shillong called Sacred Heart. The school, which was once an orphanage, is where Lou encountered his first guitar. “It was destiny, love at first sight for that guitar. Feeling it and holding it made me complete.” It was a common instrument, available for all the students to share, and whoever got hold of the guitar first would get to play it for half an hour. “There was a rotation after dinner so once in a while, I would skip dinner,” he beams. Lou joined the school marching band, experimenting with instruments like the snare drum, saxophone and trumpet, the last of which he quickly ditched after his mother told him playing it would cause him to lose all his teeth. But his love for the guitar was focused and unwavering. He sought every opportunity to find his way back to the instrument that was to lead him to a life devoted to the release of spirit through the creation and performance of music.

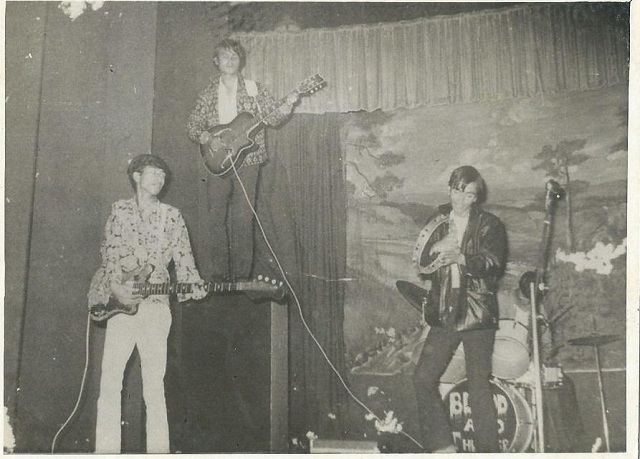

At a concert in Shillong back in the day. Photo courtesy: Lou Majaw

Soon after Lou finished high school, he found himself hastily ditching Shillong and heading towards Calcutta. The move was prompted by a dramatic turn of events: he had got a girl pregnant. “One day, I was in the house with my mother. An elderly man came over. He called me ”˜pyrsa’. Pyrsa means son-in-law. My mother’s antenna went up. [The man] told me that his daughter hadn’t eaten for a week because I had stopped going over. I said I would come.” When Lou went across, the father insisted he marry the girl. He promised to set him up with work and a home. Lou saw the offer as a great insult. Though he couldn’t support even himself, let alone a family, the thought of living off the largesse of another human being was abhorrent to the proud Khasi boy. He refused and histrionics ensued. There was screaming and shouting all around. The family began to get aggressive. Lou recalls being thankful there were no other males in the family. If the girl had any brothers, he says, he is sure they would have killed him. “It was not the first time. How many times I’ve had these kinds of setups,” he says, ruefully and also matter of-factly. He sped off to Calcutta right after the incident.

His Calcutta years were mired in struggle. Lou worked all kinds of odd jobs to survive, including as a laborer in construction and cleaning cars at petrol pumps. “They’d throw coins at you. Most of the time they’d just say, ”˜Fuck off’ .” At night, he would sleep in parks or in the grounds of Calcutta’s big mansions amongst the chowkidars, who he would befriend. They would let him sleep in their corners outside the manors, sharing space with stray cats and dogs. “It was a very interesting life. Kolkata taught Lou to survive. Through all that hunger, that pain and loneliness. There was no room for depression.” He adds, “Kolkata is the best fucking city in all of India. Despite the stench, despite the chaos, despite the pandemonium.”

It’s also where his career as a musician began. Perhaps that’s why it remains so dear to him. Calcutta represents a rebirth of sorts for the musician, who was going through a second phase of growth, his formative years behind him. Lou soon connected with old friends from Shillong and gathered fresh ones in his newfound home, eventually finding his true calling””a life in and of music. The first band he joined was called the Oracle Bones. Lou considers it the official start to his music career, since it was the first time he was ever paid for performing to an audience. Little Richard and the Small Fry’s was next, following which Lou went on to found and front a number of ”˜beat groups’, including Blood and Thunder, Supersound Factory (originally called The Vaudevilles, then changed because Lou thought the name sounded comical), The Ace of Spades and eventually The Great Society”” which went on to gain much renown in Calcutta and across the North-East.

Even before Lou’s professional tryst with music began, a scene had started on the other side of the country. Sixties’ Bombay had already witnessed the birth of the beat group movement through such bands as The Jets, The Savages (which morphed into Savage Encounter, helmed by the late Nandu Bhende), Human Bondage and Atomic Forest. Madras had The Mustangs and from Bangalore emerged The Trojans (which became truncated to The Lone Trojan when band member Biddu Appaiah departed, culminating in a successful pop career in the UK under just his first name).

Lou’s first band was called the Oracle Bones. Little Richard and the Small Fry’s was next, following which Lou went on to found many ”˜beat groups’, including Blood and Thunder, Supersound Factory The Ace of Spades and The Great Society. Photo courtesy: Lou Majaw

Calcutta wasn’t far behind, with bands like The Great Bear, a precursor to the much-revered High. The Great Society was also Soulmate guitarist Rudy Wallang’s first musical association with Lou and where he cut his musical teeth. It was not his first encounter with the man, though. Rudy recalls, “I was around 10 or 11 and saw this hippie with long hair and bell bottoms about town.” Much to Rudy’s surprise and delight, that hippie showed up one morning at Rudy’s home in Shillong, looked at Rudy’s mother and said, “Hi, Ma. What’s for breakfast?” It turned out Lou was an old family friend.”

The first time Rudy saw Lou perform, he was around 13 years old. The band was Blood and Thunder, and they were competing in Shillong. B&T won Best Band at the competition with Lou snagging the Best Vocalist prize. It inspired the young Rudy to take part in contests as well. A few years later, Rudy had a turnstile moment. He’d been given an opportunity to play a solo performance during a break in The Great Society’s set. When Rudy met with Lou to discuss it, the veteran musician asked him if he could play bass guitar. The eager young aspirant said he never had but was willing to try””soon he was a member of one of the North-East’s most respected bands. A few years later, after Lou’s long-running bandmate and axeman AJ decided to move on (his spot briefly occupied by Kalyan Baruah, now a successful Bollywood guitar player) Rudy took on lead guitar duties. He continued to play with The Great Society for 12 years as Lou’s right-hand man.

“Lou was my hero,” says Rudy. “Little did I know I would end up joining his band.” Rudy eventually left so that he could dedicate himself to playing the blues. But he continued to play with another of Lou’s bands, The Ace of Spades””which comprised Calcutta-scene heavies Lew Hilt on bass and Nandan Bagchhi on drums””at a number of Lou’s Dylan celebration concerts. Though it’s been years since Lou and Rudy shared the stage, and despite a falling out due to a misunderstanding of words, the blues guitarist has only the fondest recollections of his days with Lou.

“Lou and I were really close. He was my mentor. He showed me the way””after my dad.” ”” Rudy Wallang, guitarist

One of his favorite memories is of the time the army had imposed a curfew in Shillong. Rudy decided to while away the quarantine hours with Lou. On arriving at his home, he found Lou sitting behind the house, a couple of chairs set up in the yard. Lou had dug a hole in the ground and filled it with water and a stack of catfish. He offered Rudy a stick he had fashioned into a fishing rod. Neither of them had a single bite, recalls Rudy, but they managed to wipe out a bucketload of beers””it was time well wasted. “Lou and I were really close. He was my mentor. He showed me the way””after my dad.”

A much-rumoured, speculated and maligned dimension of Lou’s life has been the number of women he’s been with. Or, more significantly, the many he is supposed to have impregnated. The virile wanderer himself is unabashed about the fact or his reputation. But he says that while there was a time when he used to be very open about his relationships, he has since chosen to become “secretive” in the light of people’s increasing tendency to be judgmental and nasty about them. “But I am very open with the person,” he adds, smiling.

I asked him about the children he is renowned to have spawned over the years, children he never stayed back to raise. Without divulging any details, he admits that there are more than a few little Lous scattered about the Seven Sister states. Never wanting to settle down to a family life (he claims he was always upfront about it), Lou had walked away from all the women he knocked up. By extension, that included all the children his seed had sown. Except one: Christopher Dylan Majaw, now aged 13. Known to everyone by his middle name (named after Lou’s folk-singing hero, of course), Dylan is being raised alone by Lou. Why this one, I was curious to know. Lou explained that after Dylan experienced a couple of near-death situations during his infancy, Lou concluded that the child’s mother was incapable of taking care of him. He demanded she leave the boy with him and go make a life for herself in her home state of Mizoram, to which she returned and began a successful career as a singer. Lou has been raising Dylan since, playing father with unquestionable dedication, love and conviction.

Do you have any inkling how many kids you’ve spawned? Apart from Dylan and that first one 50 years ago [when you ran off to Calcutta]?

(Thinking) Seven, eight, nine”¦ I don’t know.

You don’t know any of them?

I know a couple. They [their mothers] used to call me every now and then. I used to send some money. But they’re married now.

Do their husbands know you’re the father of those kids?

No, they don’t. If they knew”¦ fuck, there’d be warfare.

The women found someone to get married to so quickly after they got pregnant?

Yeah, yeah! It’s easy! Fucking marriage”¦(snaps his fingers).

That exchange sums up Lou’s perspective on most things. What average folks would treat as monumental events, meant to be dragged and stretched interminably, are fleeting issues for him. It’s probably why his life has been so eventful and rich””he won’t allow any experience, good or bad, to linger or fester, ditching it as soon as it’s done, making way for another to come along.

One day, Lou decided to chuck up the music and become a farmer. He was in his twenties. He had been living in Kathmandu, after his Calcutta days, sometime in the Seventies (there’s that wide approximation of time again). In Kathmandu, he was known as Speed King, for his copious consumption of the drug Speed. Methedrine, Benzedrine, Dexedrine””he’d pop them all and then stay awake for two three days, wandering about aimlessly with his guitar. He earned just enough to survive by doing odd jobs. He had learned to sew in school and always carried a needle, thread and thimble with him. The freaks, as he called them, would employ him to do tailoring repairs and would pay him in money or in kind, sometimes buying him meals as barter.

“I know a couple [of my kids]. They [their mothers] used to call me. I used to send some money. But they’re married now.”

One day, he says, he “f lipped out.” He woke up feeling like he’d been floating for several months. He found his way back to Shillong, suddenly overcome by the desire to know the origins of his food. He was disturbed by the thought that it was something he had never thought about in all the days he had spent in hunger. Lou credits this epiphany to the drugs he had consumed, which he says made him think about things more deeply. He quit making music and decided to become a farmer, joining his maternal grandparents on their farm. He went cold turkey and worked full-time on the farm for over a year, calling the whole experience “very, very satisfying.” Lou would be up and out of bed after the third crow of the rooster and be out on the farm all day long. He grew rice, ginger, maize, vegetables: “Anything and everything.” He would walk for five to six hours to the market with around 300 kilos of produce on his back to sell. At the market, he would buy Spartan essentials to carry back: salt, sugar, tea, dried fish, tobacco.

The words of “Sea of Sorrow,” though written in 1966, reveal Lou’s motivation to suddenly renounce his life of excess and go to the root of human survival, to understand and celebrate the very essence of life itself. It’s a song that many North-Easterners know and love from Lou’s early days. At Lou’s celebratory concert, many in the audience were deeply moved with the memory of it.

I’ve known hunger since I was ten

And loneliness is my good friend

I’ve learnt to smile when I feel sad

When I see good times turning bad

I’m on the other side now

Across the sea of sorrow

Yes, I can see the light now

I know where the wind blows

Lou had embraced the solitary life, but at some point the loneliness began to set in. Something didn’t feel right; he had begun to feel restless. Life on the farm, though fulfilling, felt incomplete. One day, on a trip to Shillong, he met a girl who invited him over to her home. On arriving at her house, he spotted a guitar. He asked the girl if he could play it. He says it felt exactly like the very first time he had seen a guitar, when he had enrolled in Sacred Heart School. As he played, he began to understand the reason for his increasing restlessness at the farm. He needed music again. Lou began to take on gigs, performing shows after finishing his day’s work at the farm. When the gigs picked up, he drifted away from the farm. His grandparents didn’t mind when he left. Not much later, they left the farm too, and soon after that they both died. Lou says he still dreams sometimes that his grandfather would come pick him up from his mother’s house in Shillong and take him back to the farm.

Lou Majaw. Photo: Arjun Sen

Not long after his grandparents’ passing, Lou’s brother, with whom he had remained very close, was diagnosed with cerebral malaria, which took his life. Lou recalls the loss with minimal emotion. Life is as life goes, seems to be his way, his mantra, his survival method. It’s what keeps him energized and spirited. Most people experiencing a life of such event””born into poverty, raised in a religious school, the excesses of alcohol and drugs, the hermit life, a father murdered in his youth, the loss of a close sibling”” would find themselves on either end of the polarising matter of God, devout believers or fierce deniers. Lou sidesteps my question about where he stands on the issue: “I was baptized through no fault of mine,” he replies, using his disarmingly broad smile as a cue to move on.

But Lou’s ambiguous religious beliefs are no hindrance to the admiration and affection he receives from members of the clergy in the Christian-dominated town. One crisp Shillong morning, Lou took me to visit the Don Bosco Museum (also known as the North-East Museum), which houses an extraordinary memory and tribute to the history and culture of the people of North-Eastern India. Father Joseph, who administers the museum for the Salesian Society, a theological brotherhood founded by Saint Don Bosco, greeted Lou with great affection and warmth. On another floor, we bumped into a sprightly young nun called Sister Theresa, who beamed at the sight of my shorts-and-vest-clad guide, announcing her joy that “the great man” had come to visit them. There was no irony in her words, only respect and affection.

The story of Lou Majaw is in continuance. While his renown may be local””India’s burgeoning independent scene seems to be mostly ignorant of the influence he has had on it””his impact can be seen in the constant search and nurture of talent through the shows he organizes. He regularly hosts concerts showcasing new musicians””singers and instrumentalists”” offering them a platform, encouragement and wisdom. He is as fiercely stubborn about the importance of being original as he is in his devotion to the music of Dylan. His unfettered love of life and music””and, of course, women””feeds his very core. At 68, he can run rings around musicians a third his age; his reserves of stamina seem bottomless, his enthusiasm relentless. After a two-hour performance at his commemorative show at the U Soso Tham Auditorium, Lou moved the party to Cloud 9, Shillong’s de facto live music club. He proceeded to rip into a rabble-rousing set of Sixties’ and Seventies’ rock, leaping about the club as if he’d just arisen from a full night’s sleep.

A songwriter reveals himself more with his lyrics than his public thoughts. The words of “Death Is Not the End” are quite revelatory. Even if they offer no glimpse into his views on the idea of God, they provide an insight into what drives him to keep going.

When you’re sad and when you’re lonely

And you haven’t got a friend

Just remember that death is not the end

When you’re standing at the crossroads

That you cannot comprehend

Just remember that death is not the end

When storm clouds gather round you

And heavy rains descend

Just remember that death is not the end

And there’s no one there to comfort you

With a helping hand to lend

Just remember that death is not the end

For the tree of life is growing

And the spirit never dies

And the bright lights of salvation

Shines in darkness and empty skies

Not the end, not the end

Just remember that death is not the end

If you ever visit Shillong, keep an eye out for a silver streak striding by, the muscles in his girder-like legs rippling as he pounds the pavement with purpose. Wave him down and be sure to ask him how he’s doing. Then wait, it’ll come””the eyes crinkling at the corners, the ear-to-ear smile and the exuberant reply: “Still surviving!”