Sting at Lollapalooza: My Seven-Concert, 25-year Journey with the Legend

‘I’ve seen him from before I was old enough to vote, I’ve seen him take over stadiums, I’ve seen him make guest appearances, I’ve seen him recite verses. I’ve seen him slap a bass-guitar like only he can’

It’s not easy to steal a giant poster from a rock concert. The year was 2005, and, electrified by a Sting gig in Delhi, I had decided to snaffle a souvenir. It took three of us to carry one of the huge event signs to a friend’s car, where I was informed that it can’t fit inside or be tied to the roof. The wooden frame, I was told, was the problem. I asked for the car keys. A puzzled friend handed them over, at which point I lay the poster down—a massive black-and-white Sting staring up at me in the moonlight—and used a key as a knife to cut it out of the frame. It was all very The Thomas Crown Affair, if I say so myself—an art-theft film whose 1999 remake featured a gorgeous Sting cover of “Windmills Of Your Mind.” This was no mere whim, as I realized when rolling up the poster and laying it carefully across three laps in the backseat. It was a heist.

Sting was always worth the steal.

30 years ago, a friend was moving from the neighborhood and giving away his audiocassettes. The Michael Jackson tapes were naturally the first to go. By the time I arrived, what remained was rock we had never heard of, and so we scavenged based on album art—judging musicians by their covers—following flying pigs to Pink Floyd, bananas to The Velvet Underground. One tape simply featured three boys in black and white, wearing denim and mirrored sunglasses, not smiling but ridiculously magnetic. The Police: Greatest Hits called out to me.

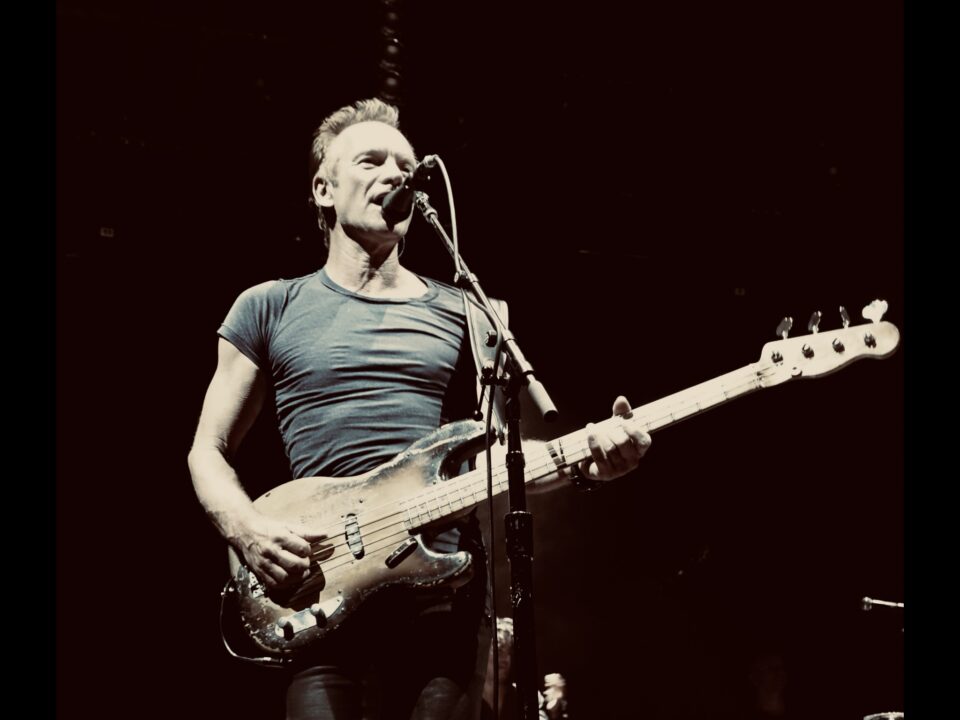

That cassette blew me away. At thirteen, I didn’t know what punk rock even was, but I knew instantly that this was special—these songs about stalkers and streetwalkers and the Sahara Desert, songs that told stories and created worlds. I transcribed the lyrics and sang along, and those songs eventually made their way to mixtapes that I used for serenading purposes. It was Sting the shapeshifting singer who first got me (I couldn’t believe “Walking On The Moon” and “King Of Pain” could be sung by the same person), then came Sting the bassist, making the songs irresistibly and deceptively upbeat, taking over your feet before walloping you in the chest.

Most importantly, for me, was Sting the songwriter, a lyricist who taught me that it’s okay for pop songs to have literary roots and influences, that all art can contain loftier aspirations. He wrote songs about Anne Rice books and about Biblical kings — yet he was writing hits. “Fields Of Gold,” for instance, which contains what is the most sensual line in rock: “Feel her body rise when you kiss her mouth.”

When Sting was called “a pretentious wanker” for writing about Vladimir Nabokov in “Don’t Stand So Close To Me,” his retort in a 1989 interview was: “What am I going to do instead? Pretend I’m stupid?” Words to live by. That song became a personal anthem, not only because Lolita was a favorite novel, but also because, years later, a girl melted every time I sang it, much like Jamie Lee Curtis in A Fish Called Wanda whenever she heard a foreign tongue. So yeah, thank you Mr Sting.

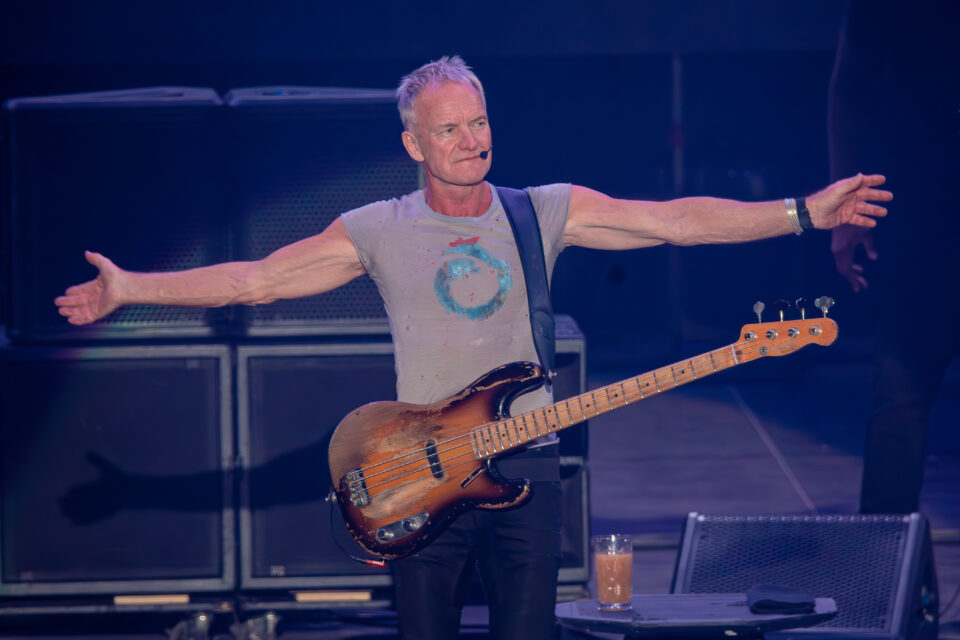

At 8:25 on Sunday night, Sting stepped onto the stage in Mumbai, bathed in blue light, and started playing “Message In A Bottle.” The crowd went wild, the band was tight, and we rapturously sang along. At 72, Sting is fierce and fantastic, every bit the bass-slapping wonder who can command a crowd. That voice is still there, still warbling, still piercing, and still impossible to imitate. Still strident as he sings “Spirits In The Material World”: “Our so-called leaders speak / With words, they try to jail ya / they subjugate the meek / but it’s the rhetoric of failure.”

Was this a political choice of song? Was it also defiant for Sting to add “Allah-Allah” ululations to “Desert Rose?” It’s hard to say, but these days every inch goes a long way—and it was a damned sight better than U2 who displayed pictures of politicians on the stage during their disappointing 2019 gig.

The first time I saw Sting, it broke my heart.

I was seventeen and incredulous as I lined up at the Indira Gandhi Indoor Stadium for the 1998 Channel V Awards, where Silk Route won Best Newcomer, and Best Indian Album went to Daler Mehndi’s “Tunak Tunak.” Standing miles away, I watched Sting sit next to classical Indian musicians—and, for some baffling reason, next to Shiamak Davar. The choreographer not only jammed with Sting but sacrilegiously added awful Hindi bits to go with “Every Breath You Take.” “Jiski surat hai, meri nas-nas mein, I’ll be watching you.” (These scars remain.)

In his bandhgala, Sting looked embarrassed. We didn’t get many high-profile international artists in India, and I didn’t know if I’d ever see Sting again, but I knew I wanted to.

A handful of years later, I was completing an MA at the University of Warwick when I realized that Sting had gone to college there. Well, almost. Just as he’d left The Police to embark on a solo career, he’d also dropped out of university. With miles yet to go before my final thesis, I remember wondering if it was an option for me as well. Yet I had already tried to play bass in a college band, to comedic results. I stayed the course.

In 2003, fresh out of university, I saw him twice in London. The first was at the Royal Albert Hall for a charity gala helmed by Queen Rania of Jordan, an evening where I fidgeted nervously in a borrowed dinner jacket, where Sting showed up but only to speak. Here was earnest Sting, rainforest-saving Sting, higher consciousness Sting, far removed from De Do Do Do, De Da Da Da.

The second was during a minimum-wage gig I had for a few months in London, working security and crowd control at an events firm. In a white shirt and thin black tie, I stood in the wings of Earls Court during Capital FM Christmas 2003. I waited patiently through performers that made my ears bleed, but somewhere—after Enrique Iglesias and before The Sugababes—there came Sting, in a striped shirt and striped pants, playing three songs. Fine, one was with Craig David, but at least there he was, slapping that bass in his way. He sang “Every Breath You Take” while I watched (suitably like a stalker) from the wings.

The Delhi concert in 2005 was my first unadulterated taste of Sting. It was a full two-hour gig, and he didn’t hold back. “Every Little Thing She Does Is Magic” bounced off the walls with its sheer heady energy. I remember “Englishman In New York” being particularly exquisite (and featuring a deliciously improvised bass solo) and then there was the softer, silken stuff: “Shape Of My Heart,” “Fields Of Gold,” and “Fragile.” The song that defined that night for me was “A Thousand Years,” a song that seemed to stretch on forever as Sting toyed with the groove, improvising, and building the mood atmospherically. An endlessly turning song about an endlessly turning stairway.

I next saw him in New York in 2011—part of his Back To Bass tour at the Roseland Ballroom—where he turned up the heat on newer songs like Stolen Car and Ghost Story, but where I finally saw him play two of my absolute favorites, the buoyantly witty “Seven Days” and the breathtaking epic” Fortress Around Your Heart.” It remains a lasting regret that I couldn’t travel to catch The Police reunion tour in 2008–2009. Those live recordings are some of the best, tightest, and most unbelievable gigs I’ve heard.

Five years ago, I saw Sting again in London—at Shakespeare’s Globe Theatre, no less—as part of another celebrity-studded gala for Peace Day. Sting only performed five songs that night, but yet another favorite was ticked off my bucket list. “There’s no such thing as a winnable war,” he sang in Russian. “It’s a lie we don’t believe anymore.” Just writing those lines out makes me hear that insistent double bass in my head.

Sunday night, then, was Sting number seven. I’ve become less driven about watching Sting again and again given all the artists I’m still longing to see, and a few years ago while on holiday in Greece, I actually passed on watching Sting at the Acropolis and ended up going for a (terrific) Nick Cave gig instead. This is partly because I’d watched a lot of Sting, certainly, but also because I didn’t want to see Sting falter. The icon hasn’t made anything new and exciting in decades, and over the last few years, he’s been singing with Shaggy.

Then came Lollapalooza. I quite love this new addition to the Mumbai music scene—a well-organized festival where the acoustics are great, a place where I run into new music and old friends—and to see Sting amidst such younger and hipper names was a surprise. This time he was coming to see me. I therefore got myself a t-shirt with the photograph from my prized Greatest Hits cassette and showed up, not expecting much but knowing every single lyric. I was 17 when I first saw him and I’m 43 now. I wasn’t expecting transcendence; I was going to see an old friend.

He started with “Message In A Bottle,” and suddenly—instantaneously— here was Sting from the poster reminding-teenaged me all over again that “only hope can keep me together, love can mend your life but love can break your heart.” Music is the most immediate means of time travel, and Sting—preposterously fit, a grey t-shirt stretched across his taut torso—took me back. “If I Ever Lose My Faith In You. King Of Pain. Walking On The Moon.” It was unreal.

Yet it was different. This time Sting was actually sitting down while performing “A Thousand Years,” a song he now says was inspired by India. The music remains mesmerizing, but this is unmistakably an older, more grizzled Sting, not going impossibly high with some of those endless ee-yo-o pitches and growling out some of the words instead. I was reminded of the iconic old-rocker concerts like David Bowie’s 50th birthday at Madison Square Garden or Leonard Cohen’s Live In London. It appears Sting has finally entered his whiskey years—what kids today would call his Daddy era.

It was glorious. “So Lonely” segued into a verse from Bob Marley’s “No Woman No Cry.” His yodels in “Walking On The Moon” were so cool and jazzy that I haven’t been able to stop hearing them in my head. “Every Breath You Take” brought the house down, after which the encore involved putting on a red light. “Roxanne” was magnificent and ridiculous, with Sting putting the audience through a vocal boot camp, making them repeat long, improvised, unfamiliar stretches—”Roxanne-Roxanne-Aa!”—after him. Unforgettable.

Sting. It’s the kind of name meant to be said out loud, to be chanted, to be cheered. A name with punch and heft, an immediate recall. The name of a boy who wore a black and yellow striped jersey too often. I’ve seen him since before I was old enough to vote; I’ve seen him take over stadiums; I’ve seen him make guest appearances; and I’ve seen him recite verses. I’ve seen him slap a bass guitar like only he can, purse his lips, and wink at the audience. I’ve seen him jump, and I’ve jumped for him. It’s impossible not to, you see. Every little gig he does is magic.