Sting in India: ‘I’ve Slept with Pilgrims by the Roadside and in the Palaces of the Maharajas’

In a chat ahead of his return to Mumbai to headline Lollapalooza India, the legendary artist talks about activism, acting and his legacy

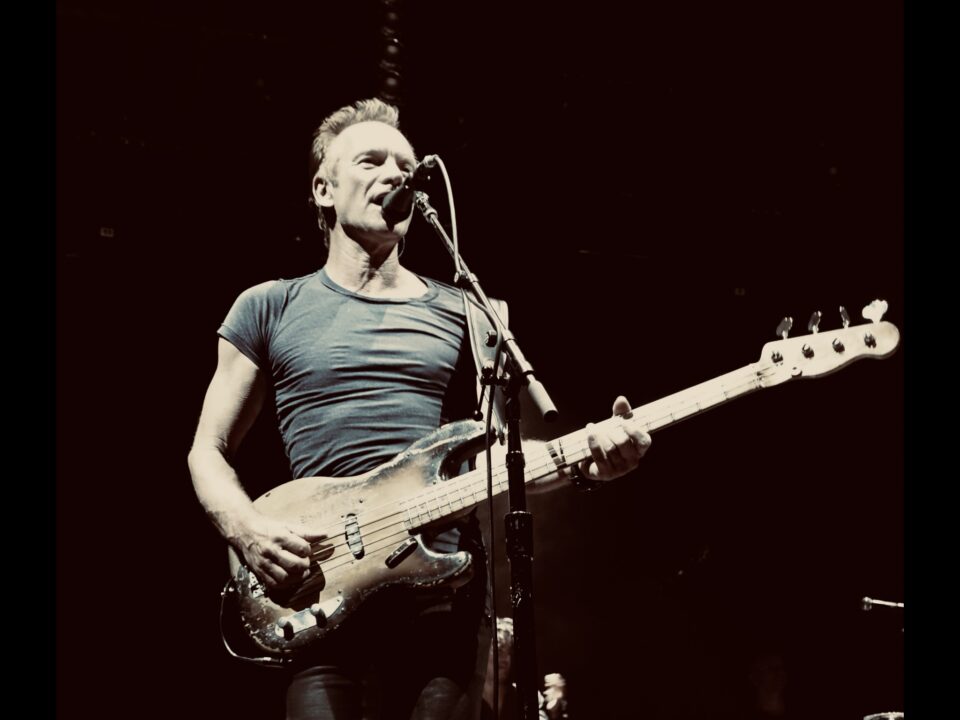

For anyone going into the Sting headline set at Lollapalooza India in Mumbai this past weekend without any prior research of setlists and the like, the cheer that went up when the New York-based British artist launched into The Police song “Message In A Bottle” was loud and euphoric.

A few hours prior at the Taj Mahal Palace hotel in Colaba, Sting – dressed all in black, seated with his legs crossed and a pair of glasses tucked inside in his pocket – told Rolling Stone India that his gig was going to be all about the hits that people will recognize. “But my job really is not to try and reproduce the recording at all, we have much more of a jazz sensibility, and that you’ll recognize the head of the song. But every night I’m searching for something that I haven’t found before, I haven’t discovered before. I’m led by my curiosity,” he says.

The 72-year-old Gordon Sumner – celebrated musician, actor (on stage and in front of cameras) and activist, among other things – is erudite, cheeky and frank in his responses about everything involving his craft. He even goes on to say that each night’s show “can go into a disaster or go to a triumph.” He adds, “I hope it’s a triumph tonight.”

A triumph it was, by most estimates, especially for a veteran artist who was headlining a recently established multi-genre music festival that had previously brought down acts like Imagine Dragons and The Strokes in their first edition in 2023. Sting has been in music for more than 50 years, unlike any of last year’s international draws. Even at Lollapalooza India 2024, he was there amongst pop stars Halsey and The Jonas Brothers (who were reportedly catching Sting from stage-side).

Following his Mumbai performance, Sting traveled to Jaisalmer to continue his association with the country he visited first in 1980 with The Police bandmates Stewart Copeland and Andy Summers. In a chat with Rolling Stone India, Sting looks back at the India memories right from 1980, acting in shows like Only Murders In The Building and his legacy.

Rolling Stone India: Welcome back to India.

Sting: Wonderful to be back. I haven’t played in Bombay in 44 years. I mean it seems ridiculous, it seems like yesterday… It’s lovely to be back here. I was there earlier this morning at the venue and it looks to be exciting.

You’ve visited here outside of performances as well, right?

I’ve been here a lot. I spent a lot of time in the Himalayas, trekking. I went to Gangotri and Yamunotri, walked from Hrishikesh. I’ve slept with pilgrims by the roadside and I’ve slept in the palaces of the Maharajas. [laughs] I’ve played in New Delhi and Bangalore, and so I think I have a good perspective on India, its complexity, its contradictions and I love it. I find it very stimulating.

Can you take us back to 1980, when you first visited Mumbai with The Police? What were your first impressions of the country?

Well, I think I had culture shock. It was so different to where I come from. I’m from the north of England, you know, it’s very grey. It’s very industrial. Mumbai in 1980 was a very different city to what it is now, there were no high rises. There was this one [Taj Mahal Palace hotel], I stayed here. We were the guests of the Jazz Club of Mumbai, which was a group of Parsi ladies, very posh Parsi ladies. And they invited us as part of the Jazz Festival. I’m not sure they knew what they were getting [laughs]. But I remember we played in this beautiful amphitheater, open air. And it seemed like the whole of India was represented in that audience. There were thousands of people outside who couldn’t get in. I was a little frustrated, because they were curious. But I remember being as curious about the audience as they were about us, because nobody knew whether it would work or not. It was such a different thing. We were the first rock band into Mumbai. After the end of 90 minutes, it was a normal rock and roll reaction. Everybody was enthusiastic and yelling and screaming and [it was] very exciting. I’ll never forget it. It was such a vivid memory, and I longed to come back. So this invitation to play the Lollapalooza festival was something I said [claps hands] No problem, please, I’m coming.

Your association with Indian music also seemed to have kept going since then, and perhaps before that too. You’ve worked with artists like Anoushka Shankar and Karsh Kale. What draws you to Indian music?

I think that the culture is so, so rich. The history is so rich and I’m a student of music and so to come here and listen to raaga, you know, trying to clap with it [claps hands referring to taal]. Very difficult. It’s a different mindset. Indian classical music is totally different than Western classical music. There’s so much to learn of rhythmically. [Jazz-fusion pioneer and guitarist] John McLaughlin is a good friend of mine, you know and he’s another student of Indian music, obviously, you know that. So there’s always something to learn and I’m hoping to learn something while I’m here.

As far as collaborations go, you had the song “Dreaming” come out with Marshmello and P!nk. What do you seek out in collaborators at this stage in your career?

It’s a great privilege to work with other musicians, especially when they’re reinterpreting one of my songs, because they will bring something to the song that I hadn’t anticipated. They can also bring an audience to one of my songs that I wouldn’t get. Marshmello is a very successful electronic dance music, and so he has an audience. P!nk, too, has a different audience to me. So it’s, it’s a win-win situation. It’s great fun to do. But also commercially, you’re expanding your influence, you’re expanding the power of the song. So I never say no, I’m always curious what people want to do.

Is there someone on your list to collaborate with right now?

I was gonna have a meeting last night with A.R. Rahman. But he got stuck in an airport somewhere. So it didn’t happen. We’ll meet eventually and we’ll discuss a collaboration, perhaps.

What comes faster or easier – lyrics or music first? There’s an eloquence in your lyrics but the music too is sometimes quite complex and elegant.

The simple answer is nothing comes easily. No, I wish I was that kind of genius where music just flows out of me. It doesn’t, I have to work hard. I tend to write music first, with the philosophy that if you compose music well, it already has a narrative. It’s telling you a story. I hear stories, when I hear music, some people see colors, I hear stories – characters, situations. And so the music writes the lyric. I am just the conduit, I think.

Activism has long been part of your life. What we’ve seen in more recent years, as the world gets increasingly online, is that activism sometimes gets perceived and dismissed as performative. Does that bother you?

Well, I mean, let’s take an example – I have been interested in what I can do in a positive way to help the environment for 30 years. Using my position as a platform to say [that] if we keep burning our forests down, we’re all going to be in trouble. I was attacked for that and they thought it was just performative. It wasn’t. And frankly, after 30 years, I wish I’d been wrong. I really do.

But I wasn’t wrong. We’re now realizing that the destruction of the forests in the Amazon is related directly to the changes in climate and change in weather. We’re all suffering from it. Frankly, it’s the poor people of the world who are in the front line of this – flooding… storms. We’re not immune in the West, either. I live in New York City, I could be flooded as well as and in London. So I think all of us need to listen to what scientists are telling us, not what politicians are telling us, because they’re generally lying [laughs].

Speaking of New York, I went past the Belnord Building, which is the Arconia in the series Only Murders In The Building, which you were part of in season one. We’ve heard what the showrunners had to say about how they got you on board, but what was your experience like?

Well, I was acting [smiles]. I suppose it was a version of me. It’s a little bit crazy.

So you don’t break into song whenever you want?

No [laughs]. What was funny is that they give you a script when you agree to do it. But that’s not the script they use. They improvise and so you have to be on your toes. And they say something to you that’s not in the script. So you have to… I mean, it’s fun. There’s the scene in the elevator, where the dog bites me, and I say, ‘I don’t like dogs.’ It’s not true. I actually love dogs. But he [Martin Short’s character] said, ‘But you have a dog.’ I said, ‘I don’t like him either!’ That was completely ad-lib [laughs].

You’ve been on stage and in front of the camera over the years. How do you switch between modes as an actor, if you have to?

I never had an ambition to be an actor. I acted in films by accident. I had the right look. I did about 12 movies, some good, some terrible. I prefer acting on stage because I have more control, it’s closer to what I do normally when I sing. Acting on film, you have to be so patient. It’s really a director’s medium, and you just have to wear the right clothes and say the right lines and then do it 50 times. My preference is to act in plays. I like that.

You’ve branched out to do so many different things across decades. Compared to when you started out to now, have you changed what you’d want to be remembered for, in terms of legacy? I feel like it changes for all of us as human beings, not just for artists.

I think up till about 10 years ago, I would have said my legacy are my songs – the songs I wrote for The Police, the songs I wrote for my own career. But now I would say my legacy, the one I’m most fond of, is The Last Ship, which became a Broadway show and a touring show in Britain and Europe. And there’s a very strong possibility that it may become an opera with a big chorus and orchestra. So that is an exciting adventure for me. I also think it’s about something very personal to me. It’s about my community, where I come from, the people I was brought up with, and also about my escape from that. So if I have to sort of say what’s my legacy, at the moment, it’s that. But you’re right, it will change. I also have six children and seven grandchildren, so that’s a legacy as well.

What are your plans in India, outside of the performance here at Lollapalooza?

While I’m here? I’m going back to Rajasthan tomorrow. I’m going to Jaisalmer, which is one of my favorite cities. I’m here for another three days.