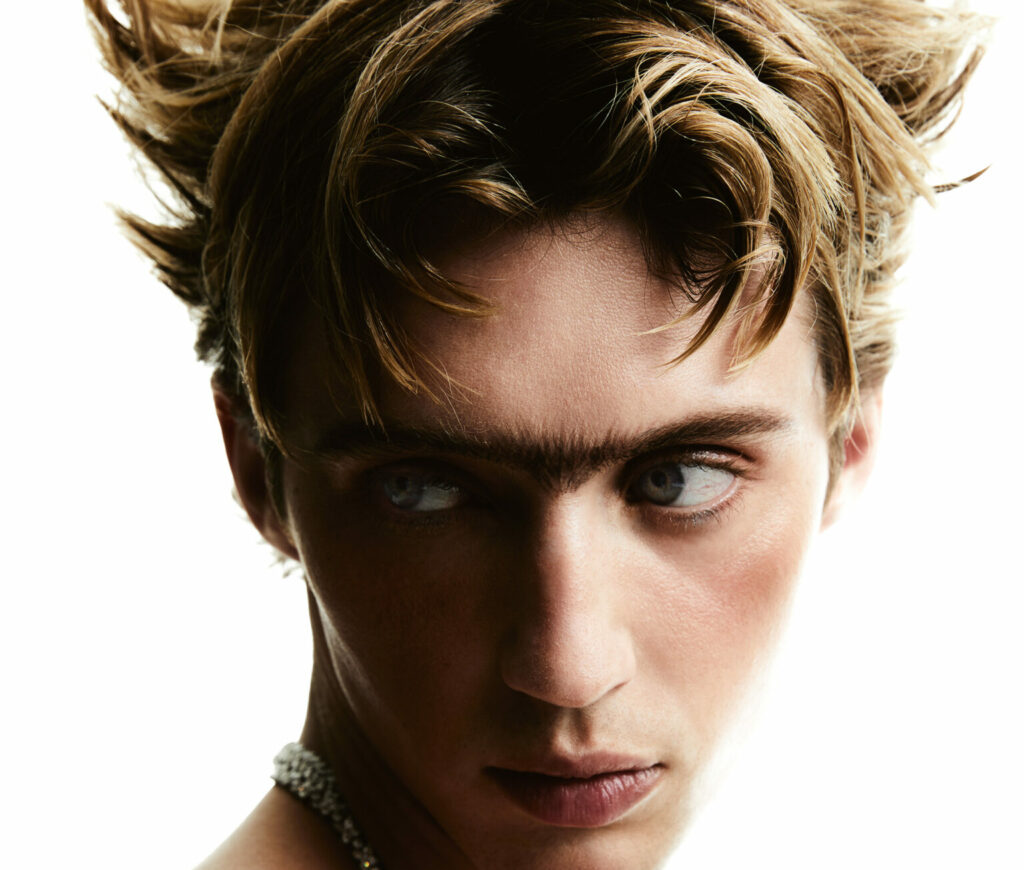

Troye Sivan: One of One

A star was born and a superstar emerged

roye Sivan is seated at a table at Holloway House in West Hollywood. He’s sipping sparkling mineral water and speaking with such addictive composure about a one-night stand that I find myself leaning forward, right palm on chin, transfixed.

“He was super, super sweet and we had a great time,” Sivan continues. “And then we ended up going to my place and whatever…,” he smiles gently, in a way that’s neither shy nor brazen. “And afterwards, he said to me, ‘Can I sleep over? Is that all right?’ I hadn’t had a sleepover since my ex. And that felt really scary to me. Like very, very intimate.”

Sivan split from his ex Jacob Bixenman in 2019 after four years together. The confusion and grief of that time is tackled in six-song EP, In A Dream, which he self- admittedly “word-vomited” out and released in 2020. But lying there, next to this new paramour, Sivan began to reassess all he thought he knew about true intimacy.

“We were lying in bed and he was like, ‘This is one of life’s greatest pleasures, connecting with people in this way.’ Obviously the hook-up is fun, but he’s like, ‘Even if I never see you again, we get to have this really special moment together.’”

He never did see him again, but the experience shifted Sivan’s perspective on relationships. It was the flutter of a butterfly’s wing that ultimately unleashed a creative typhoon.

“That really kick-started everything.”

That encounter is all over the new record, his third and undoubtedly most anticipated opus, Something to Give Each Other. The title was inspired by it, so are the songs about his emotional reawakening (‘Honey’), to his nights out on Melbourne dance floors (‘Rush’), to the lyric: “Boy can I be honest? / Kinda miss using my body”, from the song ‘Got Me Started’. It’s even in a lyric in the outro of the extended version of ‘Rush’: “To love with reciprocity is so good.”

Tomorrow night, Sivan will host an intimate launch party for ‘Rush’ at a dive bar in Silverlake. He’ll play the song once, at midnight, and hide in the bathroom until it’s over. “I don’t like it when I’m at a party and they play my music,” he says in his Australian-South-African accent that he’s maintained since relocating to LA in 2014. “It’s so embarrassing.”

‘Rush’, named after the popular brand of poppers, became Sivan’s highest- charting solo single, accruing 50 million streams in two weeks. Sivan tells Rolling Stone he took a hit for the single’s cover photo to ensure it gave off the same flushed feeling amyl nitrite offers when it’s huffed on the dance floor. Or in the bedroom, as is often the case.

“If you go back there’s this tiny vein on my head,” he smiles. “It’s my favourite part of the picture.”

If the cover artwork didn’t allude to it — a beaming Troye Sivan between the legs of a naked man – his new album era is about liberation.

It’s a natural progression from his 2018 album Bloom, where the platinum-selling title track about bottoming, and the album itself, explored a delicate vulnerability.

The 2023 era picks up where Bloom left off; it’s confident, hyper-sexualised, and destined for the canon of queer dance-floor anthems. In the same way Janet Jackson’s freshly single era was delivered with exotic warmth on All For You, Sivan’s new record sounds rich and fast, and wandering in parts. And therein lies the paradox; it’s made for a certain fandom, but it’s not that. It slips in and out of queerdom and traverses innovative pop territory; a soundtrack for every emotional experience.

Tracks like ‘Can’t Go Back Baby’ and ‘One of Your Girls’ (about being a ‘straight’ man’s secret) feel high- brow, subtextual, and new territory for commercial pop. The album sounds as if it’s from a remote hometown you can’t quite place or recall — perhaps that’s due to all the travelling Sivan did while creating the album. Written and recorded in London, LA, Melbourne and Sweden with longtime collaborators including Max Martin protégé Oscar Görres, Styalz Fuego, Ian Kirkpatrick, A.G. Cook, and Leland, the record sounds global and lavish — because it is.

Troye Sivan and Leland (who co-wrote some of Sivan’s biggest hits including ‘My My My!’ and ‘Youth’) globetrotted for almost a year together. They spent weeks in Stockholm, working at Max Martin’s MXN studios with Oscar Görres. The pair would wake in time for breakfast and discuss what they were in the mood for writing about as they ate, and then head to the studio to record it. Later, they would journey to Sydney and Melbourne — riding scooters through the city on the way to the studio — then off they flew to Paris, where they would take inspiration from the museums they would frequent, and later London, and finally LA, where they holed up in Leland’s home studio.

Sivan filmed the ‘Rush’ music video in Berlin. The titillating ode to the club community marks the boldest visual he’s ever made — thanks to joyous choreography and a cast of Berlin club scene fixtures. Next up is the clip for ‘Got Me Started’, which Sivan is filming in Bangkok. His dedication to creating a global-sounding record is all-encompassing; sonically, visually, energetically.

I notice the necklace he’s wearing under his white mesh singlet and blue pinstripe shirt is the same one he wore on the ‘Rush’ single cover, and the one he wore while starring as Xander on the controversy-ridden TV show, The Idol. It’s Cartier, he tells me, fingering the two interlocked rings hanging from its chain. “I got my friend Kerri a ring and my friend Kayla a ring, then I wear theirs on my neck.”

This article could easily be about ‘Troye Sivan the wunderkind actor’ not ‘Troye Sivan the global pop star’. He’s been pursuing an acting career since his early teens when his first manager discovered him on YouTube and put him forward for auditions. Like most of Troye Sivan’s young endeavours, his first acting gig was a success. He starred as young Wolverine in the 2009 film X-Men Origins: Wolverine. He also starred in each of the Spud trilogy films alongside John Cleese. But it was his role in Joel Edgerton’s Boy Erased in 2018, about the harmful effects of so-called ‘conversion therapy’, that cemented Sivan as an actor’s actor.

This year’s The Idol was Sivan’s first swing at television. The show’s creators Sam Levinson and Abel Tesfaye (The Weeknd) were criticised for the brazen depictions of sex and violence, poor writing and lack of character development. In a media landscape where a strong reaction to art is considered a home run, they would take the win. When I ask Sivan about further accusations of mistreatment towards the cast and crew, he speaks confidently.

“I definitely would like to think I’m a person with strong morals and if I had seen anything where I saw someone being uncomfortable, I would have been the first person to say, ‘Hey, that’s fucked, we have to stop. It’s not OK what’s happening.’ And I didn’t see it.

“I can’t speak for Lily [Rose Depp] but I read interviews where she said she felt totally comfortable on set. So for me that is kind of where that conversation ends a little bit — unless there’s some bigger picture thing I don’t understand, because I’m ‘in it’ or something. I don’t know.”

After spending the past two days observing Sivan, it’s clear he has a level of insight which escapes most. I saw it in his joyous collaboration at the photoshoot, where our team suggested drawing a monobrow on him for one look and his response was, “Yes, slay.” And how here at the restaurant he suggested we move tables to be further away from the speaker so the audio I was capturing would be easier to transcribe.

His sensitive spirit is all over his work. The record’s title Something to Give Each Other is quite literally the wrapping with which he wants you to receive it: a gift to give someone else. So when he admits he felt unphased by The Idol’s controversy, it was surprising. Then I asked him where his resilience comes from.

“It’s like nothing matters,” he smiles. “Like literally nothing. As far as work and all that goes, I’ve always known that I could go back home to Australia and my family would be there. And that’s the best. It makes you invincible to a certain extent.”

In the beginning, there was a 12-year-old Troye Sivan and his computer camera in his bedroom in Perth.

The same year, Barack Obama made history as the first Black US President, and California legalised gay marriage. At 17, Troye Sivan uploaded his coming out video, and by 18 he had accrued a following of over four million people.

Soon he would become one of Australia’s biggest music exports, with over 10 billion streams and two (soon to be three) commercially successful albums to his name. He reached a summit of stardom rarely experienced by local acts. What most don’t know is that he almost quit music entirely while making platinum- selling debut album, Blue Neighbourhood.

“I was like, ‘Damn, I wonder if the label made a mistake signing me,’” he tells me the day before, perched on a couch in jeans and a singlet at the cover shoot studio. “I was just like, ‘I don’t actually know if I’m cut out for this, or any good at this.’”

He told no one. Not his parents, not his manager, not his label; no one.

“I just didn’t want to let anyone down or like, you know, have built their hopes up because I had this YouTube audience.”

In Sivan’s formative career years, YouTube was moving the needle in ways that eclipsed physical sales and digital downloads. Justin Bieber was riding the success of his debut EP after being discovered by Usher and Scooter Braun on YouTube, and Australian A&Rs were discovering the platform’s power. EMI Australia’s Mark Holland f lew to Perth and signed Troye Sivan for the world a decade ago and, despite global distribution agreements, the local label is still considered the control centre of the Troye Sivan Machine.

Across the two days we spent together, there was only one moment when Sivan closed up. “I don’t want to talk about it too much,” he says. When Sivan was building his following on YouTube as a child, not all of his subscribers had good intentions.

Content warning: the next part of this article contains references to the sensitive and distressing topic of online grooming.

One older male fan pretended to be his manager for a time. Another fan, a man believed to be in his sixties, would send Sivan gifts almost every day to a designated PO Box. Often it would be a T-shirt or a CD, or a piece of art, but other times it would be long letters. Sivan was 12 and he kept it from his parents.

“He used to get angry at me if I didn’t respond in a timely manner to say thank you,” says Sivan. “And I had no idea. I would be like, ‘Oh my God, thank you so much.’ Like, engaging with him and stuff like that. That’s one of the more benign ones.”

I ask him about the less benign ones.

“I just had, like, bad people, you know, around when I was a kid.”

Stalking?

“Yeah, sometimes.”

Physically?

“Sometimes.”

“I feel like it’s a pretty common experience to have creepy adults online talking to children, you know. I think that’s a really common thing.”

And even fame doesn’t insulate you from the dangers that many young people face online today; in some cases, it heightens the risk of it occurring. An article by Rolling Stone’s EJ Dickson noted grooming behaviours are “both common and insidious”.

“Which is by design,” she wrote. “An adept abuser is skilled at gradually inuring their victim to increasingly inappropriate behaviour, so oftentimes they’re not even aware of what’s happening to them while it’s going on.”

Earlier this year, Troye Sivan was based in Melbourne and living with his younger siblings — his sister Sage and his brother Tyde. All three work in music; Sage is a member of indie-pop band Approachable Members of Your Local Community and Tyde is a songwriter and artist in his own right. All three were single at the time.

“The house was just this, like, revolving door,” Sivan smiles knowingly. “And my parents were like, obsessed,” he jokes. “They’re cool, they’re chill.”

Sivan is candid about his active sex life. He posted a photograph of his daily vitamins in March, with the caption “this combo keeps me gay”. One pill was PrEP, the revolutionary medication that prevents the transfer of HIV. But he wasn’t always moving around with such comfort in singledom. It took time for him to realise how much he loves his own company. In the past, Sivan would often wake up stressed and would ride the waves of emotions which follow a breakup. Now, he’s learned he enjoys travelling solo and taking himself out to dinner.

“When you first go through the breakup, it feels unfair or shocking that you don’t have…,” he pauses, “when you realise you’re alone in the world. It’s just you. And once you get over that shock — that that person doesn’t owe you anything. They don’t owe you to be with you or to look after you — you realise that you’ve got to do it yourself. It’s hard, but then as soon as you accept that, it’s amazing.

“I think out of necessity you surprise yourself. You meet yourself in that moment because damn, I didn’t know that I had it in me to go to a party by myself. Or you know, go on a blind date that you’ve been set up with.”

At the photoshoot, Sivan was wrestling with a sinus infection. “I’m going to blow my nose now otherwise it’ll annoy me the whole time,” he says, holding his nose and excusing himself.

When he returns from the bathroom, we talk about his use of male pronouns in his lyrics, starting with 2014’s ‘Gasoline’. I tell him he helped lead the charge for queer representation in music. Sivan, always the cognisant observer, says he “had it easy in the context of the queer experience”.

Aware of the privilege he’s been afforded simply by when, and where, he was born, Sivan is well known for lending his celebrity to queer causes and charitable elements. His real influence as an activist, however, is less obtrusive. He moves in commercial spaces, on your radio, on billboards, and across your social media timelines — casually inserting queer themes into the public consciousness. A young, white, charming gay man living his best life; singing about boyfriends, anal sex and party drugs. It doesn’t so much disrupt, as it does subvert. A private protest on a public stage.

“There’s this Jewish idea that the best kind of Tzedakah, which is charity, is Tzedakah that you do quietly. And it’s private,” he says.

When Sivan was writing his debut album with songwriter/ producer and artist Leland, his now longtime collaborator was terrified.

“I come from a really conservative background and a super conservative upbringing. That was such a chapter of growth for me to not give a fuck,” Leland says from Sound City Studios in LA. “To write exactly what the song calls for and not be fearful of what some conservative person is going to think of this or me.”

Now, thanks to artists like Sivan, Lil Nas X, Sam Smith and Kim Petras, queer representation in music is celebrated in a way that would make forbearers like George Michael, Freddie Mercury and Elton John proud. “I think queer generations after us are going to look back and just see how important Troye’s music is and was,” says Leland. “And how joyful it is and was. And necessary.

“But for me, it’s helped me just give less fucks and to be less fearful in how I move throughout this industry and how I move throughout my career.”

Troye Sivan’s ticket to the music industry’s inner sanctum is his uniqueness. He takes an inspired approach to music, yet he has no desire to emulate any of pop’s luminaries. He’s carving his own path based on his individual experience of unabashed experimentation. In some ways — when considering his contribution to LGBTQI+ equality — Sivan’s career could have become an avatar of queer iconography. But it’s not.

Instead, Sivan is one of one, a young renaissance man whose experiences and resulting music will have a lasting impact on not just pop music, but an entire community who, with each overt celebration of queer culture, is given further permission to live an authentic life.

“I think about a young kid in Austra- lia or in the middle of America. Or what- ever. Wherever,” he says, unknowingly playing with his hands and pushing back his fingers. “I think about if they see the music videos or hear the music, or hear the stories… If I can make them feel af- firmed and seen and recognised — or in- spired maybe to go live this happy, free, queer life — then that is something that I’m really proud of. That’s something I would really love.”

From Rolling Stone UK.