Sixty-five years after he smoked his first joint, Willie Nelson is America’s most legendary stoner and a walking testament to the power of weed. It may have even saved his life

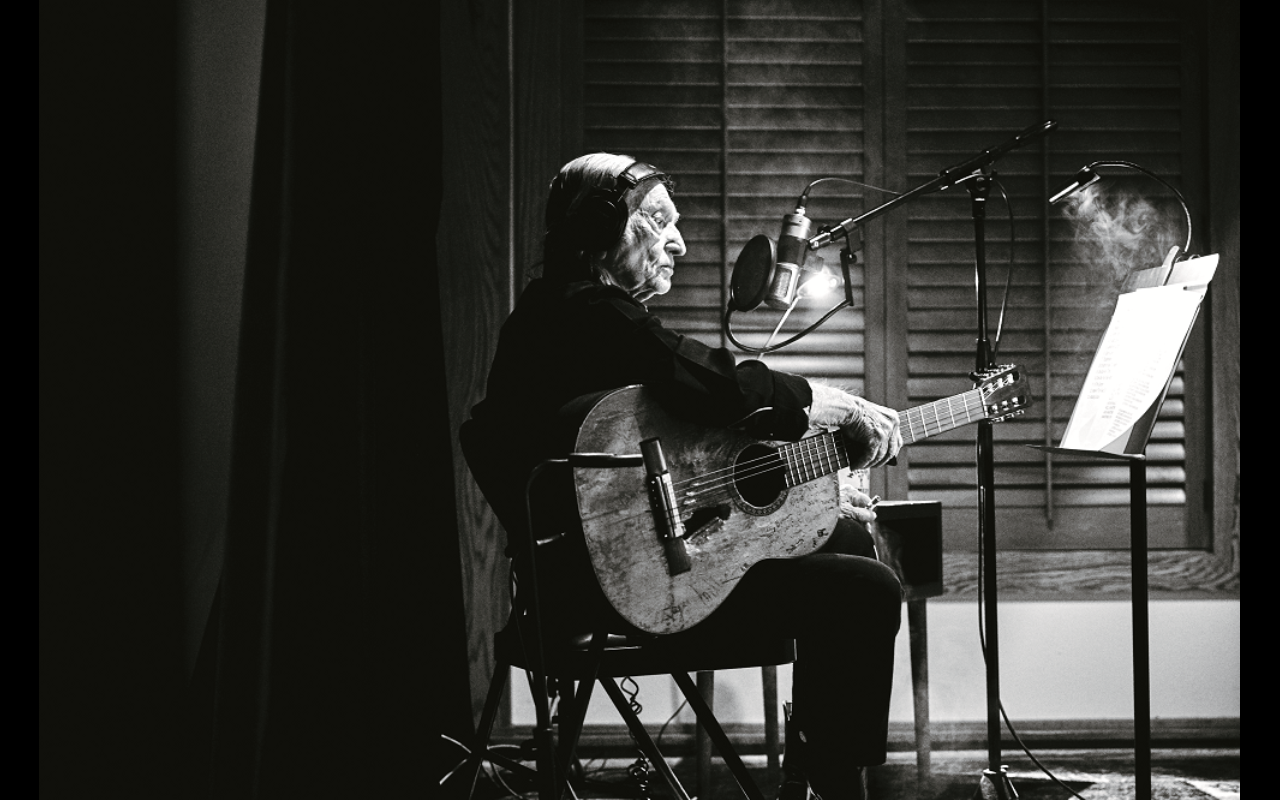

Willie Nelson. Photo: James Minchin III

Willie Nelson is sitting on a couch at his home, a modest cabin that overlooks his 700 acres of gorgeous Texas Hill Country, when he reaches into his sweatshirt and produces a small, square vaporizer, takes a hit and exhales slowly. “Wanna puff?” he asks.

Nelson’s wife, Annie, setting down a cup of coffee on a DVD case working as a coaster in front of him, speaks up. “Careful with that, babe,” she says. “You have to sing tonight.”

Nelson nods and puts it away. He turns 86 this spring and has a history of emphysema, so Annie, who’s been with Willie for 33 years, tries to get him to look out for his lungs, especially on show days. This can be a problem. “He’s super-generous,” she says, “and if there’s somebody around, he’ll want to offer it and do it with them to make them feel comfortable.”

Willie Nelson is our music superstar of the month.

Nelson says he stays high “pretty much all the time.” (“At least I wait 10 minutes in the morning,” Keith Richards has said.) His routine, Annie says, is to “take a couple of hits off the vape and then, an hour or two later, he might want a piece of chocolate. That keeps it going. So not a ton [of pot] . . . but he is Willie Nelson.” Annie recently bought Nelson an expensive version of a gravity bong — a fixture of high school house parties, which can shoot an entire bowl of weed into your lungs in one hit. “You can use ice water, which helps cool it off,” Annie says. “And no paper really helps.”

In addition to being the world’s most legendary country artist, Willie Nelson might also be the world’s most legendary stoner. Before Snoop or Cheech and Chong or Woody Harrelson, there was Willie. He has been jailed for weed, and made into a punchline for weed. But look at him now: Still playing 100 shows a year, still writing songs, still curious about the world. “I’m kind of the canary in the mine, if people are wondering what happens if you smoke that shit a long time,” he says. “You know, if I start jerking or shaking or something, don’t give me no more weed. But as long as I’m all right . . .”

Years before weed became legal, he spoke about the medical benefits and economic potential of weed if it were taxed and the profits were put toward education. “It’s nice to watch it being accepted — knowing you were right all the time about it: that it was not a killer drug,” says Nelson. “It’s a medicine.”

He pauses for a second, before telling a joke he’s told a thousand times. “I don’t know anybody that’s ever died from smoking pot. Had a friend of mine that said a bale fell on him and hurt him pretty bad, though.”

Nelson’s house is a cedar log cabin, 35 miles from Austin, with a sweeping panoramic view of Hill Country. He picked the spot in the late Seventies, laying four rocks where he wanted the foundation built. Down a dirt road, there’s an Old West town he had built for his 1986 film Red Headed Stranger. His golf course, Pedernales Cut ’N Putt (“No shoes, no shirt, no problem”), is nearby. Tonight Nelson will play a benefit for 300 Farm Aid donors; tomorrow, 3,000 people will come here, to Nelson’s Luck Ranch, for the Luck Reunion, an annual concert held during South by Southwest. A rainstorm last night tore up the property, and a crew has been working furiously to get things ready. None of this seems to bother Nelson, who just woke up. “Oh, it’s fun,” he says when asked if he minds all the excitement. (“Willie expects everything to go OK,” says his friend Steve Earle. “He’s pretty serene, so everybody else just does better than to create drama around him. That organization kind of works that way.”)

Sitting with Nelson, you get used to long silences. “Oh, pickin’ a little,” he says when asked about what he’s been up to. He also just finished an album, Ride Me Back Home. The first song is about the 60 horses on his property, which Nelson bought at auction and saved from slaughterhouses. Nelson had showed me some of the horses when I visited five years ago. “Billy Boy is still here,” he says. “We lost Roll Em Up Jack. Wilhelmena the mule is gone. Uh, rattlesnake got her. Babe, you got any of that CBD coffee?”

Nelson is talking about Willie’s Remedy, the coffee that is sold by his cannabis company, Willie’s Reserve. The idea for a weed business started a few years ago; Nelson had bronchitis and he couldn’t smoke, so Annie started making him weed chocolates. The recipe took some perfecting — Nelson kept eating too many and getting too high, so she had to lower the dosages to five milligrams. She lent some to a friend, and big business came knocking. They were skeptical — “We don’t want to become the Wal-Mart of cannabis,” says Annie, who headed the negotiations. They wanted to keep in line with Nelson’s Farm Aid organization, supporting family farmers. Willie’s Reserve is now available in six states, and it’s proving “fairly lucrative,” Nelson says. It hasn’t been easy — since the drug is still federally prohibited, “the regulations change like chameleons,” says Annie. “The edibles are actually harder [to produce legally] than the flower. You have to have specific kitchens. You have to have specific licenses that take years to get.”

Nelson’s official title is “CTO: chief tasting officer.” The company even had business cards made up. He explains: “If I find something that’s really good, I say, ‘This is really good.’ ” Despite 65 years of pot use, Nelson is not a connoisseur; he shrugs when asked for his favorite Willie’s Reserve strains. His famous stash, he says — the weed that he used to keep in a Hopalong Cassidy lunchbox on his bus — is a bunch of random kinds that have been given to him by fans or thrown onto the stage. Willie’s Reserve VP Elizabeth Hogan has been trying for years to figure out what kind of weed Nelson likes. The response, Hogan says, is usually “ ‘I claim ’em all’ ” or “ ‘Pot’s like sex — it’s all good, some is great.’ ” (“He’s kind of a sativa dude,” says Annie. “He’s already funny, so it just makes him funnier.”)

Pot has been Nelson’s exclusive drug of choice since around 1978, when he gave up cigarettes and whiskey. He’d had pneumonia four times, and his hangovers had gotten nasty. Plus, he could be a mean drunk. “I had a pack of 20 Chesterfields, and I threw ’em all away and rolled up 20 fat joints, stuck ’em in there,” he says. “I haven’t smoked a cigarette since. I haven’t drank that much either, because one will make me want the other — I smoke a cigarette, I wanna drink a whiskey. Drink a whiskey, want a cigarette. That’s me. I can’t speak for nobody else.”

He has no doubt where he’d be without pot: “I wouldn’t be alive. It saved my life, really. I wouldn’t have lived 85 years if I’d have kept drinking and smoking like I was when I was 30, 40 years old. I think that weed kept me from wanting to kill people. And probably kept a lot of people from wanting to kill me, too — out there drunk, running around.”

Nelson uses the phrase “delete and fast-forward” a lot. It’s the title of a recent song of his, and it means forgive, forget and move on — a way to get through painful times. Weed, he says, helps him delete and fast-forward. “You don’t dwell on shit a lot. The short-term thing they talk about is probably true, but it’s probably good for you.”

What do you mean, the short-term thing?

They say people who smoke pot have a short-term memory. Maybe that’s good, you know?

Why?

Because [otherwise] you start remembering a lot of negative things that you’re not supposed to remember. And the next thing you know, you’re back drinking whiskey.

So weed helps you forget about stuff you don’t wanna think about.

Yeah. What’s more important is, there’s nothing I can do about what happened a while ago. Nothing I can do about what’s going to happen in a minute. Right now? I can try to pretty much control everything.

Are there times you don’t remember stuff that you wish you had remembered because you were high?

Oh, probably. But I forgot it.

Nelson smoked his first joint in 1954. He was living in Fort Worth, working as a musician and a part-time radio DJ, and had been watching the Senate’s Joseph McCarthy hearings in a bar one night when a local musician named Fred Lockwood invited Nelson outside to “blow tea.” Nelson was anxious about trying it — “The U.S. government . . . said I would go crazy and stick up a bank and . . . murder innocent people,” he wrote in 1988’s Willie: An Autobiography. Nelson thought it was a better idea to hold on to the joint, pull over later that night on his drive home and smoke it. But nothing happened.

Photograph by James Minchin III.

“It took me about six months to get high,” he says. He was drinking a lot of Jack Daniel’s and smoking a lot of cigarettes, “so who knows what gets you high or drunk.” But he kept trying, and one night he was onstage in Fort Worth when “I finally realized I’m getting a little buzz off it,” he says.

Nelson suspects he’d had pot as a kid — his cousin had shared a doctor-prescribed “asthma cigarette” when they were fishing one day. Cannabis was sometimes available at drugstores and dance halls before FDR essentially outlawed it in 1937; Harry Anslinger, the commissioner of the Federal Bureau of Narcotics, testified that cannabis had spread from the Southwest U.S. to become a “national menace.” With Mexico just across the border, it was easier to find weed in Texas than anywhere else in the country. But “if you had so much as a seed, you got 20 years,” recalls Nelson’s friend Johnny Bush. Bush remembers a friend named Hank who worked as a cameraman in San Antonio. A police officer found a joint in Hank’s pocket. “He got 20 years,” Bush says, “and he served every day of it.”

If you ask Nelson’s friends about some of the pot-smoking pioneers of country music, one name always comes up: JR “Chat the Cat” Chatwell, a prominent Western-swing fiddler who turned every musician he could on to weed. He’d been smoking since the 1920s, and even recorded a song about it, 1941’s “Mary Jane,” with his band the Modern Mountaineers (“Pretty little girl named Mary Jane’s got me under her finger/I don’t mind my being there ’cause that’s where I want to linger”). Chat drove to Laredo and the border to buy his “cheese,” and even smoked it onstage. He turned Texas bandleader Doug Sahm on to pot and its sophisticated varieties in San Antonio in the late 1950s. Years later, Sahm showed up at the Rolling Stone San Francisco offices with a briefcase full of different strains of weed, Rolling Stone founder Jann S. Wenner said, an entirely new concept at the time.

Other musicians were more discreet. In the early Sixties, Nelson toured as a bass player for Ray Price, the slick, Nudie-suit-wearing country crooner. “I went to his hotel room one time and noticed he had a towel under the door,” Nelson says. “I said, ‘You motherfucker’ — so we quit hiding from each other.” He called the weed they were smoking back then “Mexican dirt weed.” You could get a “lid,” a tobacco can containing about an ounce, for between $10 and $20.

On the road, pot was a tool to counteract other substances. Bush recalls he and Nelson taking “bennies” (Benzedrine, an early amphetamine) to make drives sometimes as long as 500 miles between gigs, where “you’d tie the trailer to the car, put four musicians in there,” Bush says. “You’d be on a benny high and you had no appetite. Then you smoked a little, and then all of a sudden your appetite came back and you could sleep. It was a cycle.”

Nelson had his own cycle. “I used to drink a lot,” he says. “And that brings on negative thinking. You start thinking about everything that’s wrong and then you better drink another or take another shot so it gets better. And it don’t get better.” Nelson spent most of the Sixties in Nashville, writing hits for other artists, like “Crazy” and “Night Life.” But he wanted to break through on his own. A despondent Nelson famously got drunk and laid down in the middle of the city’s main strip, not caring if he got run over. Then there was the time his second wife, Shirley, got a hospital bill in the mail for the birth of his daughter, whom he had with his soon-to-be third wife, Connie. His sister Bobbie attributes his dark times to drinking: “We don’t hold our alcohol well. I might be able to drink a little wine myself, but Willie can’t drink.”

“With him, the dark side would come out,” Bush says. “His eyes are brown, and they’d go dark brown, you know. It wasn’t a physical mean, he would just get a little sarcastic.”

Nelson’s true adventures in drugs started when he moved to Austin in 1971. He grew his hair out and started playing shows that united hippies and conservative cowboys. “When Willie Nelson moved back to Texas, I stopped getting my ass kicked so much,” says Earle. “I had long hair and cowboy boots, and people took offense to that. Willie moves back, and all of a sudden, within a year or two, I’m standing out in the cow pasture listening to the same bands with the same guys that used to kick my ass. My hobby in high school became turning cowboys on to LSD, and they were so grateful.”

Nelson endorsed Beto O’Rourke during his Senate compaign in 2018: “He’s an old rock & Roll picker.” Photo: Rick Kern/WireImage

“I’m an experimental sort of fellow,” Nelson wrote in his 1988 autobiography. In the Seventies, he experimented with hallucinogens. “In the fairly short period of time that I used it, acid taught me several profound things,” Nelson wrote. “One was that I must not take acid and try to play a show.” Two hours before a show, he took 1,500 micrograms of LSD: “I seemed to be standing in chocolate pudding,” he wrote. “My fingers began turning into claws on the guitar. I felt like I looked like a werewolf.” Today he says hallucinogens are “not for me. I need to think. And some of those things, I can’t think on them.”

Nelson has been busted for pot several times, though none of the arrests led to serious jail time. After a 2010 bust in Sierra Blanca, Texas, when Border Patrol seized six ounces from him, the county attorney suggested Nelson sing “Blue Eyes Crying in the Rain” at the courthouse as punishment. But Nelson’s most remarkable bust story came in 1977. He and songwriter Hank Cochran had a couple of days off tour, so they headed to the Bahamas. The trip got off to a rocky start when the airline lost their luggage, but they went to Cochran’s boat anyway. After two days, they decided to pick up their bags at the airport. A customs agent was waiting with Nelson’s suitcase. The agent held up a bag of weed he’d found in a pair of Nelson’s jeans. He was thrown in jail. “I got deported. They said, ‘Don’t come back.’ ” Has he? Nelson gives a look and pauses for several seconds. “Fuck, no!”

Nelson’s next stop was the White House. Before the arrest, he had been invited by Jimmy Carter, for whom Nelson had performed during his campaign. Nelson was photographed arriving on the back lawn wearing tennis shoes and a bandanna. “Oh, he laughed about it,” he says of Carter’s reaction to his Bahamas bust. “Why not?”

That night, after singing in the Rose Garden, Nelson went to sleep with his wife, Connie, in the Lincoln Bedroom. Then one of the president’s sons knocked on his door.

“Chip Carter took me down into the bottom of the White House, where the bowling alley is,” Nelson says. Then they went up to the roof and smoked a joint. Nelson remembers Carter explaining the surrounding view — the Washington Monument, the string of lights on Pennsylvania Avenue. “It’s really pretty nice up there,” Nelson says.

On a Saturday afternoon in Austin, a couple of dozen people pack into the Lazy Daze coffee and smoke shop, which today has become a pop-up shop selling Willie’s Reserve products. A video is shown of some of Willie’s Reserve growers — including Tina Gordon, a San Francisco drummer who started growing in California’s Emerald Triangle, the largest cannabis-producing region in the U.S. “I feel like Willie Nelson and what he stands for really resonates,” she says. “It’s a combination of embracing the natural world . . . and ‘stick it to the Man,’ and I love that.” We also hear from Johnny Casali, who took over his parents’ farm, which included cannabis plants, then got sentenced to 10 years after a neighbor turned him in. Now he’s back to work, growing weed for Nelson.

Nelson knows he’s one of the lucky ones — he gets angry when he thinks about all the people in prison for it. Forty percent of all drug arrests are for pot, with blacks four times more likely to get busted than whites. “A lot of it is because people get in there who don’t even have the bail money to get out,” he says. “Let those guys out and start working and paying taxes.”

Nelson is talking in his bunkhouse, a one-floor wood-paneled space across the driveway from the house. Donald Trump is on MSNBC. Nelson picks up his remote, but it’s old and janky, and the button doesn’t really work. “It’s hard to turn him off,” Nelson says.

This is where Nelson comes to hang out at night by himself. A round poker table sits in the middle of the room. (“You don’t wanna play poker with him,” says Earle. “He’s not afraid to lose, so he’s not afraid to bet, and it’s hard to beat a guy like that.”) Behind it, there’s a small portable closet stacked with cowboy hats. There’s a tub full of golf balls, and a cupboard full of guns. Across the room from that is a shelf containing Nelson’s black belts for martial arts. Nelson will sometimes stay here until five in the morning, drinking coffee, watching the news or a Western, coming up with songs.

He often has his SiriusXM station, Willie’s Roadhouse, turned on. He hears a lot of old friends on it: Johnny Cash, Waylon Jennings, Ray Price. Nelson released a song about those friends, “Last Man Standing,” in 2017. Then he immediately stopped performing it. “I don’t like going to that place mentally.” Mortality is his least-favorite subject. He didn’t go to the funerals of close friends like Jennings and Roger Miller, and he makes a habit of avoiding sadness at all costs. He seems to think that’s another reason he’s survived: “When you put a negative thought into your mind and body, it literally poisons your system.”

In 1978 with Waylon Jennings, who was not a fan of weed. Photo: Bettman/Getty Images

I ask him what he thinks his legacy is. Nelson stares back intensely. He asks me to repeat the question twice more before it becomes clear he just doesn’t want to answer. “I hadn’t really thought about it. I think there’s already [a legacy] out there that people have made up their minds already. I think.”

Nelson wrote a new song last night. It’s called “God Is Love.” He speaks a verse of it, making eye contact with me the entire time: “Take these words of wisdom with you everywhere you go/Tell all the religions in the world, and through them the truth shall flow/But God is love, and love is God, that’s all you need to know.”

Nelson says he doesn’t see God as a “big guy in the sky, making all the decisions.” “I think God is love, period. There’s love in everything out there — trees, grass, air, water. Love is the one thing that runs through every living thing. Everybody loves something: The grass loves the water. That’s the one thing that we all have in common, that we all love and like to be loved. That’s God.”

The next day, Nelson teaches the song to his band in his Pedernales recording studio, an unmarked building on his golf course. The space has a lot of history. One day in 1982, Nelson woke up Merle Haggard, who’d passed out after being up for five days, and brought him here to record his famous last verse to their duet “Pancho and Lefty.” Nelson gave the band members just a few days notice for today’s session. They had no idea he was going to cut nearly an entire gospel album in one sitting.

Nelson shows up a little cranky — he’d come from a photo shoot, one of his least-favorite things on the planet. When his microphone isn’t immediately ready to go, he snaps at the engineer. But soon he warms up. Nelson in the studio is completely different from Nelson onstage, where he can sometimes coast. Sitting on a stool, he tears through take after take, songs he learned as a kid in church and early classics of his own, like “Family Bible.” He works hard to figure out advanced chord structures, giving instructions like “Let’s get that diminished in there” and “Modulate up a tone.” When someone makes a mistake, Nelson usually blames himself.

“Everybody unhappy?” Nelson says midway through, getting laughs from the control room. He asks what time it is: 9 p.m. “Oh, it’s early,” he says. “We wouldn’t even be [onstage] yet. Let’s see what else we can do.”

“He’s not fucking around today,” says the engineer.

Close to midnight, Nelson comes into the control room to hang with his son Lukas. Willie is sweaty, vibrant, and looks younger than this morning. The engineer’s microphone mistake is long forgotten, and Nelson reaches into his pocket and takes out a generous wad of $20 bills, handing them over as a tip.

After a while, Nelson gets up. “I’m gonna see if the little lady wants to drive me home,” he says. Some of the songs aren’t perfect. “We’re coming back in to fix ’em later.” He takes a hit from his vape pen and exhales. “Not sure what year that’ll be.”

The hip-hop artist reflects on his 2024 journey, including his performance in India, acting projects,…

‘Happiness’ highlights why K-zombies matter. It questions what differentiates humanity and monstrosity and what 'happiness'…

"It's not my moment, it’s her moment," the actor told Men's Health

The grime star pleaded guilty to the charge and was also fined about $2,400

Documentary on the embattled music mogul will premiere later this month on Peacock

"I’m honored to contribute to this legacy doing what I love most, rap," Fiasco wrote