After a 13-year period in which he even sold his drums, Bruford returns with a new jazz combo and memories of making Yes's 1972 masterpiece Close to the Edge

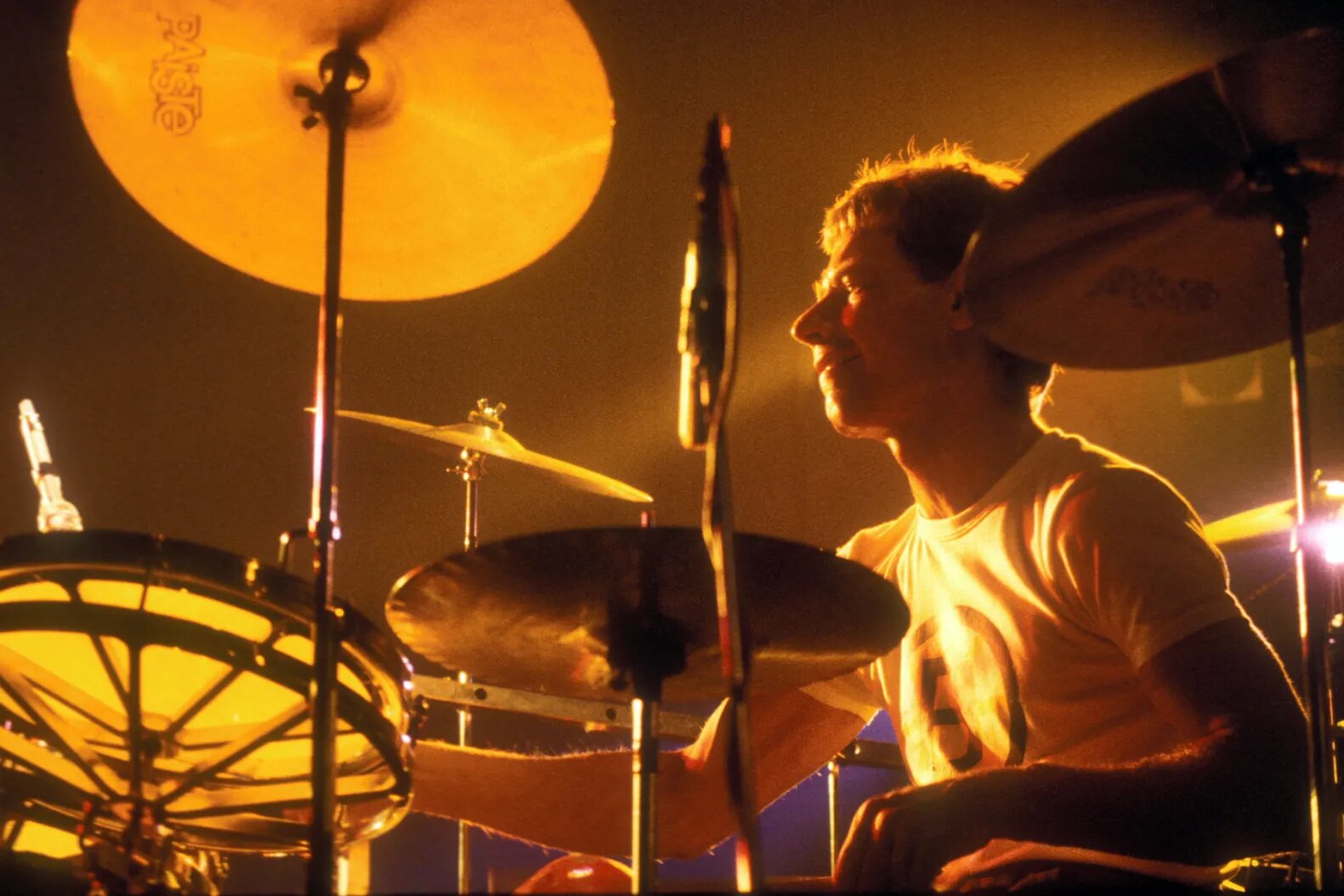

Bill Bruford onstage in 1979. After quitting music and selling his drums, Bruford returns with a new jazz combo. Watal Asanuma/Shinko Music/Getty Images

To many progressive rock fans, Yes, Genesis, and King Crimson represent the holy trinity of the genre. And the only person freakishly talented enough to log time in all three of them is drummer Bill Bruford, who pulled off the feat between 1972 and 1976. “I’m also the guy who left all three of those bands,” Bruford jokes with Rolling Stone via Zoom from his home in Surrey, England. “I’m famous for leaving bands.”

More recently, Bruford became famous for leaving music altogether. He stopped playing drums even for fun in 2009, sold all of his gear, and never planned on performing again. When Rolling Stone last caught up with him in 2019, Bruford was a decade into a retirement he thought would last forever. “I’m at the stage in life now where I just can’t summon up that commitment to play any kind of music, really,” he told writer Hank Shteamer. “There’s other things I want to do now: write books and be with my grandkids and so forth.”

Just three years later, Bruford had a sudden change of heart and started playing small-scale jazz shows around England with the Pete Roth Trio. These are the polar opposite of the massive Yes, Genesis, and King Crimson concerts of his past, but that’s precisely the point. Bruford was never comfortable in stadiums and always preferred the jazz circuit, even if it meant earning considerably less money per gig.

He first followed his heart rather than the pocketbook when he quit Yes shortly after they completed their 1972 masterpiece Close to the Edge and were on the verge of taking it on tour across the world. With a Super Deluxe Edition of Close to the Edge coming March 7, we figured this was a good time to check back in. Here, Bruford opens up about what drove his decision to un-retire at age 75.

I want to go back to the very beginning of Yes. At what point did you realize this band had something new and different?

It’s a really hard question. As a musician, you don’t really wake up in the morning and say that. Bear in mind, I was there about four years, ’68 to ’72. And for the first three years, we were falling apart financially. We were just avoiding grim death by the skin of our teeth, and how the band survived, I don’t really know.

Then suddenly, there was a bit of a postal strike in the U.K. and our manager had a word with Richard Branson, who ran the only chart in the country. If you were able to influence your way into Richard Branson’s chart, you were ipso facto in the Top 20. And we managed to do that. And then once you tell the public you’re in the Top 20, then everything’s fine.

In the earliest days of the band, you guys somehow got a slot opening for Cream at their Royal Albert Hall farewell show. What was that like?

Really scary. I think I had a tiny little drum kit in comparison to [Ginger] Baker. He was this kind of behemoth, and I’d always liked him. I grew up with him as a kid. I was going to London Jazz clubs when I was 15 or 16. There was no age limit in these places. And Ginger was not a friend of mine, but he would’ve seen this sweaty kid in the audience and he would’ve been about 22 years old or something. So I thought he was an old man.

I was hugely influenced by him. And so I suppose it was a bit intimidating playing in the Albert Hall. That said, we took a lot of the stuff in our stride to tell you the truth. I dropped a stick in a solo, but had this great big intro onto the stage with “Something’s Coming” from West Side Story. I was supposed to play something after a pause, but all you could hear was this drumstick rattle onto the hard wooden floor. I don’t think I’ve dropped a stick since.

What did recording the first Yes album teach you about creating music in a studio?

Pretty much everything. It was kind of frightening. You can have different sound mixes of different instruments in your headphones if you want. But I didn’t know that until the end of the first record. So I probably played the first record with a deafening guitar in one ear, and reverb in the other ear. So it was pretty horrible kind of experience. But I was up for learning. I’m a quick study, so it was okay.

How did the addition of Steve Howe into the lineup change the way you wrote music together?

He broadened the palette. Looking back, of course, it’s all so obviously clear and simple, but at the time I really wasn’t focused on that. I was focused on drums and drumming. But Steve had a broader color palette than Peter Banks, who was highly energetic and great fun…very, very influenced by Pete Townshend. Steve brought different instruments with him like the sitar and all these Portuguese things.

It became this revolving door. “We’ve met this guy Steve, surely we don’t need Pete.” And so Pete was asked to move along. And the same thing happened with Rick Wakeman and Tony Kaye a little while later because Rick brought an even broader palette on his instrument. We replaced Tony because Tony was really strictly an organist. And we were turning into a little symphony orchestra.

Songs like “Starship Trooper” and “Yours Is No Disgrace” on The Yes Album were pretty big steps forward for the band. I’m sure you felt that at the time.

I’m not sure I remember what I felt at the time. Every day was going so fast. Every day I was just thrilled that the band was still there. There were fairly intense conversations going on within the band about who should be in it and who might not be in it next time you turn the corner. And maybe my problem was next, maybe they’re going to get rid of me, I don’t know. But I left before I was pushed probably.

“Roundabout” became a pretty big radio hit in the States. That must have taken you guys by surprise.

Yeah, it did. That whole prog thing was kind of weird. FM Radio was willing to play longer tracks back then, even though they did hack it down to sort of four minutes or something. I was astonished coming from another country to hear this thing every 45 minutes on WNEW in New York City. It was really eye-opening for me. I had no idea, first of all, that was needed, secondly, that that was possible, and thirdly, that’s how you got a hit.

What was it like coming to the States for the first time and doing shows here?

Absolutely wonderful because we’d been trapped in the U.K. The U.K. is so small that you’ve got about two or three years before you die of boredom, and the audience dies of boredom with you too. You’ve got to find space to breathe. And of course, America was the place, but none of us had a clue how to get there.

Atlantic Records in New York had no idea what we were, really. I think they thought we were a British folk group. But we had plenty of time in those days to develop. We never knew that feeling of, “Well, this album has to be a hit or you are history, boys.” And luckily, we survived just long enough to get to the States supporting Jethro Tull.

What were your goals when you started work on Close to the Edge?

I remember one of the first goals was that we had to take longer than Simon & Garfunkel. They had just taken an incredible three months to make [Bridge Over Troubled Water], and we thought that was hysterically fabulous, and so we wanted to take three months and two days, at least, to beat the record.

Also, without it being said, we all knew that we’d got the template right on “Heart of the Sunrise” from Fragile. That was pretty good we thought. And we thought, “If we just expand that somehow…”

There are all these little instrumental interludes on Fragile. There’s none of that on Close to the Edge. It’s just three songs. That’s a real statement.

The interludes with the little songs [on Fragile] were not really voluntary. It was out of desperation. We didn’t have enough material. And this has been misconstrued several times. I said, “Look, this is great orchestra here. Let’s each one of us use the musicians to play whatever you want, whatever style. We’re all at your service. If we do that, we’ll have five tracks.”

Unfortunately, I think I was the only guy that did that. Jon had a track, “We Have Heaven,” where I think perhaps he used everybody. But basically, Rick went off and did a solo, Steve went off and did a solo, I used the entire band. Chris Squire had a large bass solo thing. So it didn’t quite work out that way, but it did fill up an album. We were a bit short of material.

Did you feel any pressure going into Close to the Edge since “Roundabout” was a hit and suddenly the label was paying attention to you?

No, not personally. There was no feeling of this “make or break” or anything like that at all. I just think we wanted to do something really head-turning led by Jon Anderson who had big ambition…never short of ambition, Jon. And I followed that and was totally keen on that. But as they say, I’m afraid you’re talking, really, to a drummer.

It probably sounds weird to you, ’cause I was in the middle of all this Close to the Edge prog thing, but I grew up as a jazz guy. I liked the instrument and the playing of the instrument, the performance on a drum set more than rock or jazz. I don’t really care whether it’s rock or jazz or your wedding band, so long as I can do something on the kit that amuses me and hopefully you.

From what I read, the band logged some really long days in the studio recording Close to the Edge. Do you recall it as a particularly stressful time?

Yes. Very long hours. And then we’d pack up the equipment and go up the motorway and do a one-nighter, come back, unpack equipment, set it up again, now with a slightly different sound, of course, because everything’s changed, and reconvene halfway through “Siberian Khatru” or something.

Remember, we were young and energetic. I didn’t know what was good or what was bad. I’d never been in another band. Maybe this was really easy work. Maybe it was really hard work, but I didn’t complain. I think we probably thought it was great, but you should never trust what a musician tells you about how he felt when he was recording X, Y and Z because musicians have perceptions that change all the time. Looking back now, I see it was all pretty swimmingly great.

What do you remember about piecing together all the little parts of the title track together?

A lot of edits. There was a two-inch tape going around and around, and we kept adding in edits. [Producer] Eddy Offord, or Edit Offered as he became known, he’d just be slicing two-inch tape all the time ’cause we would do eight-bar sections and we would try sticking that section to that section. Sometimes we got lucky, sometimes it was really shit. But as I say, the good angels were smiling down on us and somehow we got this thing done.

It’s amazing there are that many edits since it sounds so cohesive.

Nobody was really guiding it. Somebody said, “Well, this might go well here.” And we all said, “Well, yeah, that’s a pretty good idea,” until we get a better idea and we probably didn’t. And by that time, it was four in the morning and everybody was exhausted, and somehow it got done.

What did you make of Jon’s lyrics? Were you ever like, “What the hell is a ‘Siberian Khatru?’”

Yeah, but I took an early view on lyrics where I decided that I don’t really care about them terribly, other than the fact that they have a sound and they have a rhythm. And both those things are really important to me. Close to the Edge is a nice phrase. “Close to the Edge/Down by a river,” very nice.

I made no suggestions at all. I never said, “What is this about?” I don’t have to have the thing be about anything. And Lord above, I certainly don’t have to have a lyric about how unhappy some 17-year-old girl is or how unhappy Jon is or my mind’s stressed. I don’t need that at all. As a drummer, I need rhythm and there’s always rhythm in the songs, and good tempo from the singer. I like the sound of the word. So a Siberian Khatru, I don’t know what it is, but it sounds okay to me.

I’ve read that you guys accidentally threw out some master tapes while making the record. What happened there?

We had to leave the studio around dawn every day. We had to vacate the place before the cleaning lady came in so that they could open up again at 9 a.m. or whatever it was. She came in and cleaned the place up, but also threw away some tapes that it turns out were kind of critical.

I think Eddy Offord had left them lying around on the desk thinking she wouldn’t touch the desk, but she saw what she thought was rubbish and threw it away. I remember going out with others to the trash, and you had to rummage through the trash cans and we did find it. We found some tape and Eddy stuck it on the machine and damn me, if it didn’t work…But it was the right thing. And I think it’s on the album too. It’s a great story. The cleaning lady affected everything.

During the creation of the record, did you start thinking that you wanted to leave the band?

I don’t know when exactly that idea came into it. Well, I’d been flirting with Robert Fripp for a while, and we’d been on tour together, I think, probably before the making of Close to the Edge, or maybe just after. And I sort of let him know I wanted to be in King Crimson. And with Close to the Edge, I had this overwhelming feeling that it was time for me to move on.

Why?

Because I couldn’t do any more in the band. I’d given as much as I possibly could. I would simply merely repeat myself, and it wouldn’t be as good the next time around. And I don’t have the patience for that kind of thing. I also don’t think it’s what you pay me to do. I think a musician has an obligation to work at his highest sensibilities as much of the time as is possible. And if you’re just sitting around doing the same thing nightly, which is my problem with large-scale stadium touring, that whole thing, I’m not really cut out for that.

I’d rather have fresh guys, fresh material, fresh problems. So I had just this overwhelming feeling that I really should get out of the way. And blessing upon blessing, there was Alan White, a friend of Eddy Offord, and he was hanging around towards the end of the album. He maybe came to the playback of the thing. It never occurred to me that he would be the drummer, but it made a whole lot of sense. So I was happy with that, and I think he was happy with it too.

We spoke to Steve a few months ago, and he said he was devastated when you left. Do you recall that?

Bless him. Jon felt that way too. I did as well. It was difficult to leave such a creative place, but also very frantic, very verbal-ish. There was a huge amount of arguing and waiting and arguing and then more arguing, more conversation.

And remember, I’d only played in one group. I’d seen these people my whole musical career, which was about four or five years. It was only those guys and people like me need to change. Close to the Edge was a good time to do it. It turns out that, of course, there was always a tour. Now that the band’s getting famous, they’d gone ahead and booked a whole tour. I didn’t know about that and nobody asked me. So I said, “Well, I’m leaving now.” And they said, “But we’ve got a tour coming up in a week’s time.” But I didn’t feel any need to apologize. I feel that I’d given my best and that I had more to give, but not in that particular band.

Was King Crimson a more fulfilling experience for you?

It was another fulfilling experience. Why? Because I don’t wait until it’s horrible. I know what I’ve done. I know when I’ve done my best. I know when I’ve run out of ideas.

I spoke to Rick a few years ago, and he told me that making Tales From Topographic Oceans was one of the worst professional experiences of his life. He hated every second of it. Is any part of you happy that you weren’t on it?

No. No part of me is happy in that sense. I haven’t even heard that record. I’m not a follower of bands when I’ve left them. I don’t really listen back at all. So I don’t know the record, but I’m, with hindsight, glad I didn’t have to traipse through all that. It was a double album, I think.

Yeah. Just four songs though.

Wow. That’s too much for me, probably. But yeah, I’m happy with my choices. I’ve been very fortunate as a musician. I’ve played with lots of guys now. But in 1972, I’d played with about four. I’ve now played with lots of guys and learned a lot of course, ’cause that’s how you learn. You don’t really learn by playing “Close to the Edge” nightly in stadiums.

How did you feel about the punk movement when it broke out in the late Seventies? I know it was very polarizing for people of your generation.

Well, it came and went pretty much. We were in the States so much. We sort of read about it a bit and kind of heard three chords played by the Sex Pistols. I thought that sounded all right, I didn’t mind that at all. And it certainly didn’t seem to affect our sales or financial position in any sense at all. So it didn’t impact these great behemoth rock groups, which by that stage, Robert Fripp and people were saying were dinosaurs and that we should stop. He stopped doing that in 1974, which was intelligent, I think.

I spoke with Greg Lake a few years before he died. He said that prog disappeared up its own ass in the late Seventies. “It got so overblown and we looked like turkeys onstage,” he said. Do you see truth in that?

Absolutely. And to the credit of Robert Fripp, he led a stripped-down King Crimson in 1980, which was a wholly different thing. I thought that was brave and exceptionally good. It was a whole new repertoire of music that could not really be called prog. It didn’t show the manifestations of excess and over-slowness, the long capes and things that we’d abandoned in 1974.

What was your experience like in Anderson Bruford Wakeman Howe? It must have been weird to go back and play that material again after all those years.

It was a little bit. It was funny because when we started, I thought I was doing a Jon Anderson solo record actually. And we went out to Montserrat, which now no longer exists pretty much, and I thought we were doing Jon’s record. But there at the airport was Rick, Steve, and their manager, Brian Lane. And suddenly I thought, “Oh, this is looking like a whole different thing,” by which point I was a bit involved. The making of the record was very easy because the tracks had been already sorted out by Jon. We didn’t have to sit in a rehearsal room and argue about the bass part.

Making the record was easy, and some of it was very fresh. I had an electronic [drum] set by then sounding quite different. And there was a little window that opened around the song “Birthright” where I felt very creative. There were moments onstage with Rick and Jon and Steve and me that I thought we could have had a second album. There was something that we could grab onto here, which was a newer, more stripped-down way of looking at music, as it were. However, it was not to be because it was taken over by the suits.

On the tour, you finally had the chance to play “Close to the Edge” onstage.

And it was lovely. I’d never played it on the road before, so it was nice to play it ’cause it’s great fun.

How was the whole Union experience?

No good.

Why?

Too many people. Too artificial. It’s a kind of Hollywood idea. It was a mad idea, I think, seven or eight odd people [playing at once]. It was a kind of fantasy that a record executive would dream up. So it wasn’t a great place to be. But on the other hand, if you’re overpaid for doing very little, as I was there, you can often take that money and inject it into some other project you’re working on like Earthworks, which is a band I ran for 20 years and feed the money into that. So that worked well.

How did you and Alan divide up the drum parts on that tour?

Pretty badly, I think. Mostly, I was on electronic drums and playing percussion to his heavy rock drums. Occasionally, I think I played maybe “Heart of the Sunrise” alone, something like that. One critic I thought put it really well. They wrote that “Bill Bruford was Hollandaise sauce to Alan White’s meat and potatoes,” which I thought was really nice. It was about right.

Rick told me he calls the Union album “Onion” because it makes him cry.

That’s a good one, yeah.

Did you feel the same way?

I haven’t listened to it.

But you’re on the record.

I’m on the record somewhere in there, but it got computerized to death. It got run through all kinds of machinery, completely unlike Close to the Edge, which I’m sure this new [Close to the Edge deluxe edition], there’s all kinds of additional bits and remixes and probably straightening out of this and straightening out of the other. But me, I’m an old-fashioned kind of guy. I like Close to the Edge when I left it as the record that I heard in the studio on playback, and it sounded great.

It was fun, and you could locate everybody, and it was human and it was warm. There were probably mistakes in there. I can hear bits that I wince at where I wasn’t on the money, but that’s the record we got. And I love that record so much that I don’t really care for all this other stuff that a record company feels obliged to sell you.

The Super Deluxe Edition, I haven’t heard it yet, but I’m unlikely to listen because I don’t need remixes and stuff. First of all, I’m not an audiophile. I’m not a collector. I’m not a listener. I’m a performer. It’s the performance in 1972 that I liked, and I don’t need to hear another version of it particularly.

Many fans feel Close to the Edge is the high-water mark off the entire prog era. Do you think that’s justified?

Well, I regret to tell you I’m not much good at these comparisons and lists. There are different prog albums, different best prog albums, but it was definitely up there and it’s been very popular and it’s given people a lot of warm feelings. It gives me a lot of warm feelings. I love the record, I think it’s terrific.

You went to the Yes Hall of Fame induction when the band was in the midst of a civil war. What was that like for you?

There was always a civil war happening, and that’s part of the reason you don’t want to spend too much time in these bands. Because there’s always something like that going on. I don’t recall much about it other than I just said, “Well, Alan can play the drums on this. I don’t want to play drums on this thing.” But I was happy to attend and lend whatever enthusiasm I could to the event.

But I think that Jon and Steve were getting on very badly. And to this day, it’s a very odd relationship between Jon and Steve. I don’t know what happened, but something happened. But as I say, I’m an outsider now.

You didn’t give a speech that night. Did you plan on giving one?

I could have said a few words if Rick Wakeman would have shut up. He gets the ball rolling and about 20 minutes later, people are saying, “Wind it up.” I felt actually really bad for Scotland Squire, who had her little daughter. I think Scotland wanted to say something on behalf of Chris and she would’ve gone before me and I think she was ready to do something. So I felt bad as Rick went on, but hey, that’s rock and roll for you.

You stopped playing drums in 2009. What happened?

Exhaustion and a kind of burnout. But you wouldn’t have noticed it in me particularly. It’s just a depth of tiredness. It’s not to do with yawning or anything like that. It’s just that you can barely pick up the drumsticks and think of what to play. And you certainly can’t think of anything fresh to play.

What causes that is overwork, and what causes that is jazz. You want to play jazz, it’s going to hurt. There’s no money, you’re going to do it yourself. Whatever it is, you lift it, you mail it, you do it yourself. You rent vans, you book tickets for people who may or may not turn up. It’s rough work. And I am okay for that. But after 20 years of that with Earthworks, I was tired.

All I knew in that tiredness was that I really wanted to do something else. I wanted to go to a university and study for a doctorate, which I did, and it took five years. And then I was an academic author for about another seven years.

What brought you back to music?

One day just passing the drum kit as I did every day in my office, I thought, “Damn, that looks good,” like an ice cream. I thought, “I’ll just have a little play and see if I can remember anything ,” ’cause 13 years off is a long time. If you’re doing fine motor function stuff like an instrumentalist like me, it’s going to take a minute or two to figure out which stick goes where. And sure, I got behind the drums again and spent a couple of years working at it until about, I don’t know, 2022 or so.

Where did things go from there?

I met this great guitar player named Pete Roth, and we hung out. We rehearsed in a local room around here, just so I could play a bit, find out where I was. We played with him and after a while, we started to get good. Somebody then says, “Well, there is this bass player, why don’t we…” You see a bass player in your rehearsal, next thing you know you’re playing at the local pub down the road. And pretty soon, one thing leads to another, and you’re back doing gigs. But I should say these are entirely different to playing with Yes. This is not the same thing.

I have no intention of doing big stadium stuff. It doesn’t really work that way. The group I’m with called Pete Roth Trio, we are playing jazz festivals and jazz in small theaters and clubs and pubs in the U.K. and Europe.

How did it feel the first time you walked onstage after all these years?

I’m not sure we were very good, but it was lovely to get started again. I had all sorts of questions for myself. “Can you play that? Is it idiotic for somebody who’s 75 years old to try to adopt the language, the vernacular of the instrument that is being played in 2025, when you started in 1967? Is that humiliating? Is that dignified? Is it undignified? Is there anything you can contribute?”

My whole gig is, “What can you bring to this? Can you bring anything nice? Bill, can you bring anything fresh?” I don’t want to hang up younger guys if they feel that I’m not cutting the mustard.

Did the impulse to sit down at the drum kit again surprise you?

Absolutely. For 12 of the preceding 13 years, I had no idea I was going to do that. I’d sold my drums. I had to scramble around to find a drum kit. Obviously, no cymbals, nothing worth talking about here in my house at all. It’s a small house anyway, so I had no idea I was going to do that. So it was like a bolt of lightning, and an undeniable one too. Once it goes into your head, you’re going to do this, I’m quite determined. So I felt, “Yeah, I’ll give this a shot again.”

But you don’t have any interest in scaling things up and forming a new version of Earthworks or anything?

No, I’m not going to do a new version. This is a more electric thing. I’d rather stay with what I have right now, but we’ll see what happens. Maybe in a year’s time, I turn it into something else, I don’t know. But for now, I’m very happy playing small places in the U.K.

Have you seen Yes at any point over the past few years?

I have. I announced them onstage at a big theater in London on their 50th anniversary tour. But I don’t feel emotionally connected to it any longer. I was emotionally connected at one point, but a lot of water goes under the bridge. Now, I’m just watching some band play this stuff. And I’ll tell you what was quite interesting watching it, musically.

In what way?

The young guys in the band…anybody under 50 grew up with a click track and they play in time. It’s kind of a religion you’ve got to play in time. And the young guys were fighting the older guys, who don’t really play in time, but they lean up into the tempo and the tempo was to go ahead. But the daylight between the young guys and old guys got lighter as the evening went on.

Are you amazed that a band you started in 1968 is still going?

Yeah. There’s something amazing about that. Maybe it shouldn’t keep going. I’m not a great fan of geriatric rock. I’m not good at that. I don’t see myself as a rock guy. I’ve just reverted to type, which was basically a jazz guy.

If Yes asked you to come onstage and play one song with them now that you’re playing again, would you do it?

I think I’m asked that twice a week, and have been for about 15 years. And the answer remains, “No, thanks. I’m fine. I’m not going to do that.”

Are you hoping that Jon and Steve will find a way to put their differences aside and perform together again?

No, I don’t hope for those things at all. Funnily enough, Jon and I have something in common. I think we’ve both returned in a way. Jon had a lot of time away from Yes, and he’s returned with this fresh thing and a new album. He’s putting new miles under his belt, which I think is great. And I feel kind of the same way.

What are your goals over the next few years?

I’d still like to be a good drummer and be very good in the ensemble I’m in, no matter what it is, and also contributing fresh things to it. Shoot me if I’m not. I’ll leave if I’m not contributing something to the music. But I’d like to keep doing that and getting better at it and staying as musical as possible. There’s a lovely line that somebody said the other day: You don’t give up drumming when you get old. You get old when you give up drumming.

From Rolling Stone US.

Mumbai singer-songwriter teams up with guitarist-songwriter Debanjan Biswas, with the video also including an appearance…

The trial of Frank Butselaar, who pleaded guilty to tax fraud, lifted the veil on…

The song will appear on Gomez's collaborative album with Benny Blanco, I Said I Love…

A judge ordered the rapper to pay a penalty and answer questions under oath in…

Premiering March 18, the film will explore the aftermath of Wade Robson and James Safechuck…

Check out our verdict on recent releases by funk/groove act Juxtaposed and ambient artist Eashwar…