The Pulsing World of Nitin Sawhney

As he heads to India for his first ever live show this month, Sawhney speaks about his most recent album, the thrill of scoring music for Deepa Mehta’s adaptation of Midnight’s Children, and the connection between gaming and Hindu philosophy

Considering all nine of Nitin Sawhney’s albums proudly display his Indian heritage with elements including tablas, qawwali, ragas, Kathak rhythms, Sanskrit poems, and songs in Hindi woven into the DNA of his spellbinding music, it’s odd that he’s never played a live show in India. “I feel comfortable in India and it’s the first time in three years that I’m going, normally I’m there much more frequently,” says the classically-trained pianist, flamenco guitarist and club DJ.

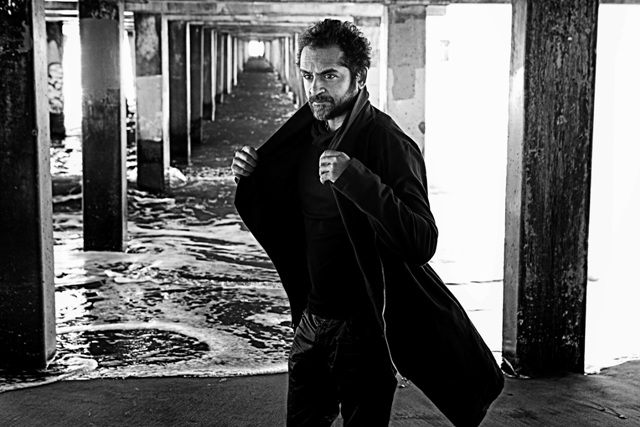

This anomaly will be laid to rest this month when the tall, lean (“patla” rather than “healthy”) Sawhney will take the stage at Blue Frog in Delhi and Mumbai, and the Sulafest in Nasik. “Previously I’ve only DJ-ed in India, which is strange as touring India with my band is something I’ve been thinking about doing for a very long time but it’s never worked out. So I’m really pleased it’s finally happening,” says the 47-year-old as we settle into a sparse, spare room adjacent to his studio, located in a converted 19th century dairy in Brixton, South London, one of the areas at the heart of the London Riots in August last year.

Sawhney’s a perfectionist so there are no half-measures or cutting corners when it comes to these shows, which are part-retrospective of his career and part-showcase of November’s album, his ninth, Last Days of Meaning. “I’m taking a full band, there’s 11 of us and the band’s really strong – we did a few gigs late last year which went fantastically well,” says Sawhney who’s casually dressed in jeans, trainers and a T-shirt.

The British-born composer, who was part of the Asian Underground scene alongside artists such as Talvin Singh and Asian Dub Foundation, attracted attention with Beyond Skin, his fourth studio album, that was nominated for the Mercury Prize in 1999. Since then Sawhney has helped conceive groundbreaking comedy sketch show Goodness Gracious Me, has written music for video games and has collaborated and written for the likes of Sting, Sir Paul McCartney, Brian Eno, Shakira, The London Symphony Orchestra and Cirque Du Soleil.

The British-born composer, who was part of the Asian Underground scene alongside artists such as Talvin Singh and Asian Dub Foundation, attracted attention with Beyond Skin, his fourth studio album, that was nominated for the Mercury Prize in 1999. Since then Sawhney has helped conceive groundbreaking comedy sketch show Goodness Gracious Me, has written music for video games and has collaborated and written for the likes of Sting, Sir Paul McCartney, Brian Eno, Shakira, The London Symphony Orchestra and Cirque Du Soleil.

The sweet stirring magic of Sawhney’s finessed, swirling arrangements of flamenco, drum & bass, dub, folk and soul, belies the fact Last Days of Meaning addresses a deeper, powerful message. “I try to catch a sense of the zeitgeist, of what’s worrying me but I didn’t want to make an album that was overtly about politics. Hopefully Last Days of Meaning captures the parochialism, narrow-mindedness, and paranoia that’s been fed by political opportunism and media in the last ten years.”

Sawhney achieves this through the clever device of Oscar-nominated actor John Hurt (Midnight Express, The Elephant Man, Alien) portraying a bitter, lonely old man railing against a changing world whether immigrants, terrorism and technology, between tracks. Gentle, stark folk dominates the album and sits comfortably alongside billowing sitar and tabla funk, drifting ethereal vocals, and school choirs.

Last Days of Meaning’s combination of balancing politics with elegant music is a tried and tested method for Sawhney and makes him stand out in an increasingly bland, anodyne, music industry. Beyond Skin explores identity and challenges India’s quest to be a nuclear power; Prophesy (2001) questions whether technology makes us happier; Human (2003) celebrates unity in a divided world; Philtre (2005) offers a soothing balm for a troubled planet driven by conflict while London Undersound covers 7/7’s terror attacks, the rise of celebrities and media dumbing down.

One of Sawhney’s key beliefs is celebrating the beauty and power of cultures crossing over, and the message really hits home in his live shows when the complexities of fusing flamenco and qawwali, tablas and drum & bass, and blues and ragas, and the extraordinary vision and subtlety of the music, comes to vivid, spine-tingling life. There are few things as mesmerizing as tabla maestro Aref Durvesh furiously matching a drummer beat for beat, a rapper spitting lyrics in time to Kathak tatkars (“ta thai thai tat, aa thai thai ta”), or a droning sitar and bongos providing the backdrop for Sanskrit poetry. Sawhney is usually either perched on a stool with flamenco guitar or on keys and is the enigmatic, unassuming centrifugal force around which it all, dizzyingly, revolves.

The grace, emotion and originality in Sawhney’s music makes him an ideal choice for composing the score to director Deepa Mehta’s film adaptation of Midnight’s Children, Salman Rushdie’s landmark novel that many cite as one of the greatest of all time and which is scheduled for release later this year.

The grace, emotion and originality in Sawhney’s music makes him an ideal choice for composing the score to director Deepa Mehta’s film adaptation of Midnight’s Children, Salman Rushdie’s landmark novel that many cite as one of the greatest of all time and which is scheduled for release later this year.

How closely has he worked with Mehta and Rushdie on the score? “It’s been very collaborative. Salman Rushdie’s been in the background, but he co-wrote the screenplay with Deepa, which I think he needed to do to retain his vision of it. Deepa and I have been talking and working through themes, over-arching narratives and characterization. We discussed at length what ragas might be appropriate for certain characters, so the film ties in with Indian history and keeps that authenticity.’

“I’ve come up with a system of melodies based around ragas, with each raga attached to a character. That gives the score a sense of rootedness and complements the characters’ feelings. Salman Rushdie got in touch with me via Twitter and said, ”˜It’s the best score since Ravi Shankar and Pather Panchali’. For him to say that was amazing, the guy’s a genius, I love his work,” says Sawhney, almost disbelievingly.

Both Rushdie and Mehta are pariahs of sorts: Rushdie lived in virtual hiding with a security detail for over 15 years and still keeps a low profile following a fatwa ordering his death as a result of the publication of The Satanic Verses in 1988. Similarly Mehta has been dogged by Hindu extremists, and labeled anti-Hindu, since Fire (1996) which depicted a lesbian relationship in a Hindu family, forcing her film Water (2005) to be shot in Sri Lanka.

Is Sawhney worried by working with controversial figures Rushdie and Mehta? “No, it’s great to work with giants like Salman and Deepa. They are controversial characters, because they’re intelligent and not afraid to say what they think. People are threatened because they have strong ideas but there are things Salman says I agree with and other things he says I don’t agree with and the same applies to Deepa. As creators of amazing, imaginative work, I couldn’t be happier working with them,” says Sawhney.

Rushdie, Mehta, and Sawhney’s collaboration not only reflects the growing influence of the Indian diaspora but in terms of reflecting the book is a match made in heaven. “I’m of Indian heritage but grew up in Britain, Salman Rushdie has a Muslim background and Deepa’s of Indian background but lives in Canada and together we’re working on Midnight’s Children, which is about fragmentation.”

Sawhney’s no stranger to scoring films; in fact releasing albums is a small part of what he’s achieved over the past two decades. In recent years he’s conceived a soundtrack to the silent 1929 Indian film Throw of the Dice, a magnificent, Mahabharat-esque tale of romance and adventure directed by Franz Osten, with the London Symphony Orchestra. He’s taken this on tour to Chicago, Toronto, Florence, Auckland, and Amsterdam, and hopes to bring to India in the future. “I’d love to project the film onto some palace walls,” he says.

Sawhney’s no stranger to scoring films; in fact releasing albums is a small part of what he’s achieved over the past two decades. In recent years he’s conceived a soundtrack to the silent 1929 Indian film Throw of the Dice, a magnificent, Mahabharat-esque tale of romance and adventure directed by Franz Osten, with the London Symphony Orchestra. He’s taken this on tour to Chicago, Toronto, Florence, Auckland, and Amsterdam, and hopes to bring to India in the future. “I’d love to project the film onto some palace walls,” he says.

Sawhney will be scoring the king of suspense Alfred Hitchcock’s The Lodger at the British Film Institute, again with the London Symphony Orchestra. Surely Sawhney’s one of the few people on the planet who’s as comfortable and capable with a globally renowned orchestra in the world of classical music, as DJing in clubs and releasing a mix for iconic, revered UK club and bastion of electronic music, Fabric.

Also in the last five years, workaholic Sawhney’s been gradually immersing himself in sound design for video games. Rather than a teenage time-pass, he sees video games as the cutting edge of technology, and culture. “I really enjoy working in gaming it’s an emerging art form. Seeing the physics of motion in virtual reality really interests me. People dismiss gaming as trivia but it’s an expression of consciousness, that’s why gaming interests quantum physicists too, they relate to Hindu philosophy too,” he explains.

It’s observations like these that evidence a keen, enquiring mind and make Sawhney the ultimate dinner party guest. Here’s a man who connects video games with Hindu Vedas and the Big Bang, discusses politics in Burma, race relations in Britain, Fox News’ disinformation and the London Riots (“a symptom of a capitalist society out of control”). He can effortlessly light up a room with stories about his mate Paul McCartney (he appears on LP London Undersound), A.R. Rahman who he took for dosa in London over 15 years ago only for Rahman to be harassed by a waiter insisting on photographs, or how his cousin, actress Lara Data is due to give birth around the time of his India gigs. “She said to me either she can come to my gig or I can come to her delivery,” jokes Sawhney.

Whatever the scenario, in the company of Sawhney it’s easy for hours to pass in what feels like seconds, as conversation turns from economics to string theory, via virtual reality and flamenco’s roots in Rajasthan folk music. However, as he heads to India for his first live shows in the motherland and meetings on big projects that he’s not allowed to reveal just yet, all you need to know is more than anything else, Sawhney’s music does the talking.