Susmit Bose: ‘Most of My Music Was Written Casually’

The legendary singer-songwriter opens up about his meetings with Pete Seeger, Jimmy Page, Nelson Mandela and more

Every once in a lifetime one encounters a musician who combines the attributes of talent, versatility of range and uncomplicated simplicity of delivery with an innate gift of musicality; such a musician is Susmit Bose, a man with a long and illustrious career that has gone largely unheralded because of the times in which it flourished. His contribution to the music scene is remarkable for its range and expanse. His new album release, Then & Now in December 2020 encompasses his 50 years on the music scene – but by no means does it tell the entire story of his contributions. For that, we have to dig a little deeper…

Some people are born destined to become musicians. They are brought up in an environment of music and musicians. It is the only way of life they know. Becoming a musician is an almost inevitable by-product of this environment. Bose is one such musician. He was born in a home where his father, himself an accomplished singer was head of the All India Radio in Delhi and curated their music programs. His friends, some of the great Hindustani musicians of the day were always in and out of their home.

Bose, steeped in the tradition of music, decided to forge his own, unique path and has several accomplishments to his name, including performing on stage with Pete Seeger, meeting and presenting an album of his tribute to Dr. Nelson Mandela and brainstorming with Jimmy Page of Led Zeppelin fame.

Starting out as an urban folk singer, when Bose was nicknamed the Indian Bob Dylan, he was singing musical tales from his experiences. He has since worked with baul folk singers from Bengal and young rock musicians from the North East. He has curated albums with diverse music genres and even worked with jazz musicians.

In the mid-1960s, a young American urban folk singer, Bob Dylan was singing protest and socially relevant songs, with lyrics and tunes he had composed. The relevance of the lyrics and the urgency and emphasis of its lyrics were lost on audiences outside of the U.S. and Dylan’s music was merely…. well just music.

The method and vehicle by which the music brought the message to the people was not lost on a young Indian musician; thus, Bose, an already accomplished musician, a singer-songwriter created his own lyrics to bring his feelings about society to his audiences.

Since Dylan was singing largely in protest of America’s engaging in a useless war with Vietnam, his messages were quite specifically anti-U.S. Government policies. On the other hand, Bose’s social environment, although not perfect or ideal did not profess or threaten war or other military activities. His angst was, arguably of a somewhat more philosophical type.

Thus, Bose sang about social changes and a musician is supposedly telling stories and Susmit Bose was a master in this endeavor. In fact, he continues to tell stories about matters as diverse as New Money, his own personal dilemmas and does not spare even his own wife and mother-in-law in the process. He has been telling these tales now for over 50 years, all original and unique.

Sadly, his singing career grew and prospered in an era when few recordings were made in India when social media and the internet – which ensures instant communication and thus reaches large audiences was non-existent and the only radio and TV channels were government-owned and ran All India Radio and Doordarshan. Bose and others from the Seventies and Eighties were operating essentially in isolation and have gone largely unknown as a result.

Rolling Stone India decided to dig into the career and the thinking of Bose and had a long chat with him. Here are the highlights of this conversation with the artist.

We believe you have strong musical roots, and your upbringing was in an atmosphere of music and musicians. How was it growing up in this environment? Was this the spur for your career as a singer and songwriter?

Well, I grew up in Delhi. My father, Sunil Bose was head of All India Radio (AIR). My father was a well-known singer especially of the Thumri and has several recordings. Before that, was a rich tradition in my family of being associated with the arts. Every great musician of the time was in the home of my grandparents in Calcutta at one time or another.

It was the Fifties when radio really dominated that dad became the AIR director. There was no TV and AIR was the only radio station operating in India. Several musicians dropped into our home. While many are considered music legends, they came through as humble, ordinary people. But their music was of a very high standard. I was influenced by Hindustani classical music and thought perhaps I would one day become a Pandit Susmit Bose. But this was also the time of a father being supremo in his home. My father did not encourage my yearning for singing Hindustani classical music and, I guess his word was law!

I took to playing the guitar and singing. By the Sixties and early Seventies, it was the dichotomous time of the Vietnam war, Women’s lib, man on the moon, anti-establishment feelings and the search among the young for a new world order. Naturally, I was caught up in this upheaval and shaped my thinking and my music. I joined a group of hippies and traveled to Kathmandu to ‘find’ myself!

How was this experience influencing the songs you wrote?

My early writing (of music) just happened. In the 1960s everyone was trying to express themselves through different arts – poetry, paintings, music, etc. The young were quite confused for directions and were making random statements. I wrote ‘I Am a Walking, Talking Contradiction,’ which summed up my musical direction!

You seem to have been reacting to your environment and circumstances. What did you write and sing about after that?

Most of my music was written casually, perhaps in keeping with the atmosphere of the times. I wrote ‘Winter Baby’ and a tongue in cheek ‘Money Talks But Cash Yaps,’ addressing the nouveau rich culture surfacing at that time. My album Train to Calcutta was an amalgamation of these diverse concepts.

That certainly qualifies you as an urban folk artist. You have documented in song the prevailing social conditions of the times. It was what Bob Dylan was doing in America at about the same time, only he was singing about the unnecessary involvement of his country in the Vietnam war, dragging in the Americans of his generation. Was Bob Dylan an influence on your style and musical substance?

No, not directly. I gather my words from events and people, so life becomes a major influence. The structuring is from the Guthrie Gharana of Pete Seeger, Woodie Guthrie and Bob Dylan. The emotion was from my Hindustani musical orientation and Indian folk singers, particularly the bauls.

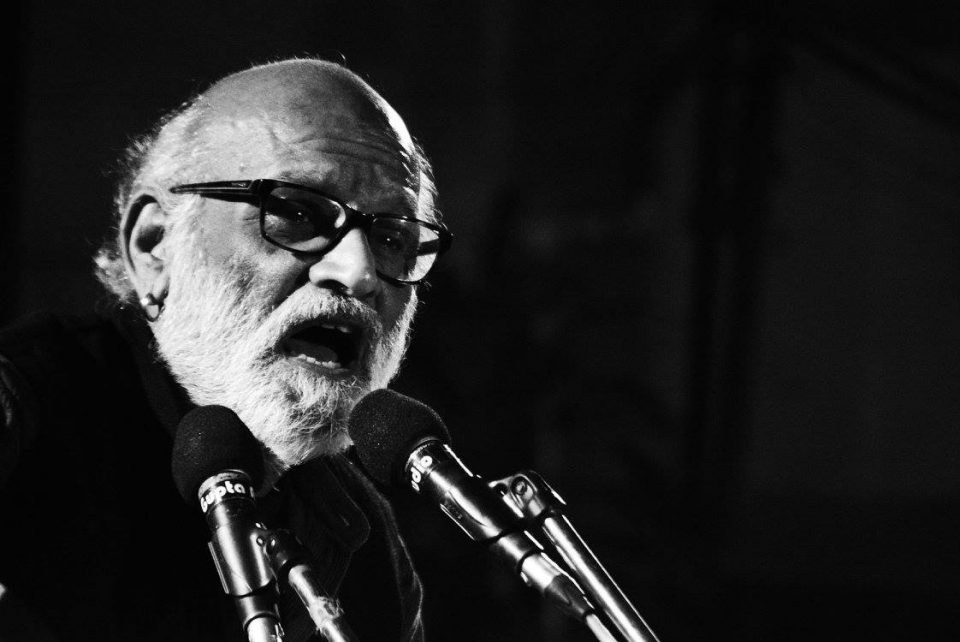

Bose with Pete Seeger. Photo: Courtesy of the artist

How did you end up performing with Pete Seeger at that huge concert in America? What is the relationship with Seeger?

My album Train to Calcutta in the mid-1970s had some international exposure and brought me in contact with Pete Seeger. He wanted to sing my song ‘Walking Talking Contradiction.’ He also wanted me to perform with him in concert in America soon thereafter. Unfortunately, because of strict travel regulations of the times that did not happen till a few years later. In 1981 a playground on the banks of the Hudson River in New Jersey was inaugurated and Seeger had worked for its creation. He invited me for the inauguration concert.

That is quite something, but I don’t remember any mention of this at the time. I suppose it was a sign of the times in India; we were quite insulated from the world. You can tell us now what you sang at that concert.

Among other things, it was memorable for our singing together of ‘This land Is Your Land’ where he sang ‘From California to the New York Island’ and I sang ‘From the High Himalayas to Cape Comorin.’ My lyrics must have surprised him. He paused for a moment, presumably in surprise and went into a banjo interlude, still smiling and looking at me!

What was the reaction back home in India to your performance on stage with an American legend?

There was no ‘mass media’ to speak of at that time. The airwaves and TV was monopolized by the state-run AIR and Doordarshan, the newspapers were staid and not interested in reporting beyond the news and perhaps some sports and of course, there was neither the internet nor the social media for communication. So, a handful of people heard of my performance only by word of mouth!

Was Pete Seeger a musical influence on you in your years of development? How did this happen?

At school in Delhi, we had as a theme ‘The Spirit of India’ for the annual school day. We had inspirational poems like Tagore’s ‘Gitanjali’ recited by a girl when suddenly I heard a song on the PA system where the lyrics were, ‘I can see a new day soon to be, when the storm clouds are all passed and the sun shines on a world that is free…’ My hair stood on end and I had goosebumps from those words. I ran to the audio booth to ask my music teacher about this song. He handed me this album on the cover of which was the picture of a tall man with his head tossed back playing an instrument which I learned later was a banjo; that was Pete Seeger and instantly I wanted to be like him! It was like hopping on to a train I had almost missed! As I then heard about the civil liberties movement and the involvement of my mother and father-in-law in them, I gave up the idea of becoming Pandit Susmit Bose and became a singer-songwriter dedicated to social change. I reached out to Pete and we have been in touch since the mid-70s.

And why was the guitar the instrument of choice for you?

I learned my playing on warped guitars borrowed from friends. I picked up chords from hippies and fellow university students, but my understanding of the guitar was that of an accompanying instrument. And like the Guthrie family, my guitar playing was simple, the three-chord format and the fingerpicking style. I liked that sound rather than the ornamental style of other musicians. I think of my guitar as a ‘chey tara’ (six-string) like the ‘do tara’ (two-string) of Indian folk musicians.

Apart from the concert with Pete Seeger, have you performed elsewhere in the world?

I traveled to and in Havana, Cuba at the Folk and Political Song Festival, at McMaster University in Ontario, Canada, at a huge stage in Moscow. Again, none of these were covered by the media in India.

Now you can tell us about some of these international experiences.

In Havana, one met great artists from all over the world with whom there was interaction. We played together for a few of the concerts. I remember a Japanese singer who spontaneously interpreted my lyrics for the benefit of his Japanese delegates!

Another experience was in my days in Kathmandu, when I was ‘finding’ myself. A fellow musician in my group was explaining the chord structure of ‘Stairway To Heaven.’ His name was Jimmy. Someone pointed out to me that was the great Jimmy Page of Led Zeppelin fame, the man who had composed this masterpiece!

For all the creativity, excitement, and adventure of being an urban folk singer, how have you managed the commercial aspect?

It is always difficult for a freelance artist to have a regular income, perhaps more so for a musician. One learns to improvise and create opportunities. In the Seventies, Eighties and even part of the Nineties, the nightclubs in metro India were very popular for live entertainment and I did my share of performing on this circuit.

Do relate some of your experiences on the ‘commercial’ circuit?

I had a fairly hectic schedule in those days. There were people like Usha Uthup and jazz singer Pam Crain also doing these popular gigs. One was always running into them and several other regulars.

A particularly electric, literally ‘electric’ incident that comes to mind! A number of artists were performing at an event. Pam Crain and popular vocalist Don Sehgal had preceded me on stage. While in the middle of my performance, Pam Crain came running onto the stage shouting that Don Sehgal had suffered an electric shock in handling some wiring backstage! In the event, he was attended to immediately and was fine, but the drama was palpable.

Years later, I was putting together an album, India Unlimited which was curated by me. Diverse musicians came together for this album – Pandit Jasraj, Louiz Banks, Pam Crain and several others were featured on this collection. Sadly, that was the last time I met Pam Crain.

Bose performing at the United Nations concert in New Delhi. Photo: Courtesy of the artist

Finally, please tell us how your historic meeting with Nelson Mandela took place.

Because of India’s great support for the anti-apartheid movement in South Africa, Dr. Mandela chose India as his first international destination after becoming the South African President.

A record company (CBS) asked me to do a music album in honor of his visit. This album was the creativity of Vishal Bhardwaj and K.J.Singh and was called Man of Conscience. It had a song in it called ‘Mandela.’ I sang the entire album and had the privilege of presenting this album to Dr. Nelson Mandela in person in New Delhi. It was a stirring experience.

You were at Mumbai‘s famous Jazz Yatra in 1978. What is your interest in jazz?

Well, all music is one, ultimately. I was thrilled to hear such great jazz from the masters. Just for that, I have to leave you with a quote from Miles Davis, which might well apply to me: ‘I am not what I do, I do what I am.’