Halsey: A Rebel at Peace

She’s one of pop’s most outspoken young hitmakers. Now she’s coming to terms with the person behind the persona

This may come as a surprise to no one, but Halsey is pretty good with a knife. Today she is wielding it against a cucumber, which would seem like a joke or a meme — given her man-eater rep in the pop-star pantheon — were it not for the bowls of lettuce idling nearby. “I’m kind of on autopilot,” she says over her shoulder, blade flashing. A few days back, she’d thrown friends an Easter feast of “baked ziti, rosemary rack of lamb, garlic Parmesan chicken, angel-hair pasta, meatballs, a fillet, mashed potatoes, bacon-wrapped asparagus, green beans and roasted potatoes,” she says. And this being L.A., “It kind of stressed me the fuck out because I was like, ‘Of the four trays of ziti I’m cooking, which one’s vegan? Which one’s gluten-free?’ ”

Today, she’s making a spicy rigatoni, a dish in which she takes much pride. “Have you ever been to Carbone?” she asks, referencing a New York establishment famed for its version, with which everyone is obsessed because they haven’t yet tasted Halsey’s. “With all due respect to the chef — because they’re so nice to me there — every time I eat their spicy rigatoni, I’m like, ‘I can make this way better.’ ” She decisively plops some cucumber into the bowls.

Her house is lovely: an unpretentious and airy midcentury gem perched on the sloping side of one of L.A.’s affluent hills and designed by the same architecture firm that built the tower of Capitol Records, her current label. She has another house, one that’s more “like a bachelorette pad with a crazy bar that’s themed like the Playboy mansion,” but she moved here about a month ago to work on her third album — a studio is currently being constructed out back — and the house has grown on her in a way she hadn’t expected.

In fact, she says that the only time she’s left her home in the past three days was for a grocery run this morning, which she insisted on making herself despite the obvious peril of being a famous person out in the wild. “I’m 24 fucking years old,” she says. “I’m a grown-ass woman. I can’t be this fucking co-dependent, helpless thing who has someone who does everything for them, ’cause I’ll fucking kill myself. I will literally go crazy.”

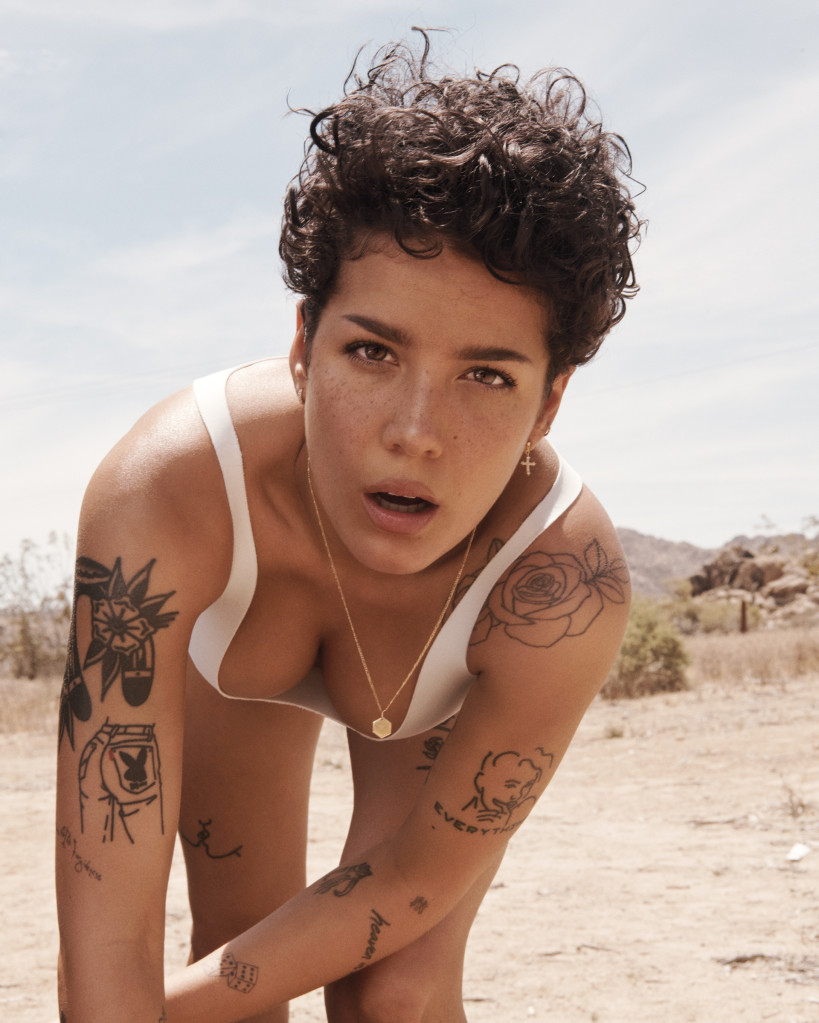

Halsey photographed in East Lancaster, California, on May 13th, 2019, by Paola Kudacki.

Right now she seems anything but, as she stands in sneakers over the stove asking just how spicy her spicy rigatoni should be. “Do you like it spicy?” she asks, giving the pot a little stir. Her face is bare, and her short hair is obscured by a scarf — not one of her 60 wigs in sight. In her paint-splattered jeans, she looks like the upper-middle-class art-school kid she might have been had her parents actually been upper-middle-class and able to afford the tuition at the Rhode Island School of Design, the dream school she got in to but couldn’t afford to attend. Instead, Halsey grew up in rough-and-tumble Garden State towns, spending the first bit of her life in her parents’ dorm room, she says, before they dropped out of college, got jobs as a security guard and a car salesman, and eventually had two more kids.

Because of their youth and temperaments, Halsey sort of parented herself. “My parents didn’t do shit,” she says, good-naturedly, tossing things into the pot without measuring them. “I had to learn to cook for myself.” The only thing at all amiss in her kitchen is the bandage wrapped around the middle finger of her left hand, the result of a cooking mishap a few days back. “Are you squeamish?” she asks before whipping out an iPhone photo of the bloody damage. She brandishes the middle finger of her right hand. “Good thing I’ve got another one.”

So it is. As an artist and even as a person, Halsey has always been polarizing for reasons that she’s still not quite sure she understands. Almost from the moment her debut single, “Ghost,” was released in 2014 — a song she wrote and recorded in a friend of a friend’s basement and uploaded to SoundCloud — she’s been cast as a bit of a punk: over-the-top and in-your-face, just a little too spicy. For one, she was hard to place — messier than Ariana or Beyoncé, rougher than Lana or Lorde — a pop star with a rock sensibility. For another, she was a maximalist. No chorus was too big, no album concept was too heady. She seemed to operate, permanently, at 11.

And despite the haters, it worked. Both of her albums — 2015’s Badlands and 2017’s Hopeless Fountain Kingdom — went platinum, and teens the world over started dying their hair her trademark blue. “Closer,” her collaboration with the Chainsmokers, topped the charts for 12 consecutive weeks, and “Without Me,” a song about her breakup with rapper G-Eazy after “getting cheated on in front of the entire world, like, a billion times,” became her first solo single to hit Number One.

Meanwhile, Halsey poked and prodded the beast of public opinion: When she tweeted about her bipolar disorder, was she destigmatizing mental illness or romanticizing it? Was it right that she called herself a black woman (her father is black) but passed as a white one? And a sexy dance with another woman on The Voice notwithstanding (“It was supposed to represent a power struggle, but it was completely unspecific”), was she truly bisexual if she was only publicly dating men?

Now, in her sunny and spotless kitchen, with an artfully arranged cheese plate resting on the counter and the pasta water coming to a boil, Halsey looks at me, smiles and adds some more spice to the pot.

Back in high school, back when she was still Ashley Nicolette Frangipane, back before she took her stage name from a subway stop in Brooklyn near where a heroin-addicted boyfriend once lived, Halsey was a misfit, hiding out in the art room where the bullies were unlikely to venture. Never mind the AP classes, the gymnastics routines, the school yearbook she edited; these wholesome activities were undercut by others more suspicious to the teenage mind: cutting off all her hair, playing music in the coffee shop of the neighboring town, going to shows in the city, and speaking her mind. When she was 15, she talked her mom into letting her get her first tattoo; in fact, they went to get matching ones together.

The animus of her high school peers drove her online, where Tumblr became a dumping ground for artwork and poetry and songs she’d written satirizing such things as Taylor Swift’s relationship with Harry Styles. There, she could see what people responded to, and she could see that they responded, for some reason, to various versions of her. She dropped out of community college, which she found to be a waste of time, and doubled down, creating a platform before most people understood what that was. “My mom was like, ‘Your real life sucks. You have no friends. You decided not to go to college. You live in this fantasy world on the internet,’ ” she says. “And I was trying to explain to her, like, ‘I’m building a brand.’ And she was like, ‘You’re building a fucking what?’ ”

Leaving home to couch-surf in Brooklyn and the Lower East Side gave her a chance to give that brand a test drive. “Nobody knew me, so I could be anyone I wanted to be,” she says. And what she wanted to be was “just an amalgamation of other people I liked. A little Jagger, a little Alex Turner, a little Patti Smith, a little fucking Effy from Skins, a little Clementine from Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind, and a little Winona Ryder, Girl, Interrupted. It was everything that spoke to my fabricated angst, you know?”

Technically homeless, she romanticized her bohemian life online and kept the ways in which she struggled — the minimum-wage jobs, the indignities of having only $9 to your name — to herself. Recently, when she talked about sleeping with men merely for a place to stay, “it of course turns into this hyperbolized fantasy of ‘Halsey the Hooker,’ ” she scoffs. “I didn’t have a pimp, no one was handing me money. But I was definitely dating dudes I wasn’t into because I could crash at their apartment. I was having sex as a means of survival. I’m lucky that that’s all it was for me; for other women I knew, it wasn’t just that. That’s the point I was trying to make.”

Whatever she was doing to get by, it turned out that what she was expert at was creating a story and then manifesting it in real life, so much so that when she turned up for a meeting at Astralwerks with all her possessions in a bag at her feet, she seemed so fully formed as an artist that Glenn Mendlinger, the guy who signed her, couldn’t help but think, “ ‘Are we being punked?’ She was talking about the arc of campaigns and mood boards and textures, and she had 25,000 followers on Twitter.”

It’s a power she still wields, turning stories into realities in her day-to-day life, setting the scene and casting herself into whatever role she fancies. Last night, for instance, the scene was “Indie Film” and Halsey was the artsy heroine, with a supporting lead in the form of her boyfriend, Dominic Harrison, otherwise known as the British alt-rocker Yungblud. “We were just sitting around in our underwear working on poetry on our typewriters like fucking losers in an indie movie,” she says. “I ordered Chinese food, listened to almost the entire Beatles anthology, went to sleep around two or three.”

It is a fact of her life, and a condition of her bipolar disorder, that Halsey does not always quite know what version of herself she’ll be when she wakes up. Diagnosed at age 17 after a suicide attempt, she says that she has for some time now been in an extended manic period that she knows won’t last forever. “I know I’m just going to get fucking depressed and be boring again soon,” she tells me, frowning. “And I hate that that’s a way of thinking. Every time I wake up and realize I’m back in a depressive episode, I’m bummed. I’m like, ‘Fuck. Fuck! This is where we’re going now? OK. . . .’ ”

Halsey. Photo: Paola Kudacki

The mania, she thinks, may suit her, even if it can make her more volatile, more prone to doing “crazy shit.” She’d been manic the first time we met too, when I wrote about her in 2016. That day, the plan had been to meet in New York’s Central Park for a “picnic,” though Halsey and I had gone straight for the Veuve Clicquot rosé. We were both in a precarious place, and we could somehow sense that in the other. Before long, we were talking about the miscarriages we’d recently had and weeping together in the midday sun. Later, the same Halsey who has been unremittingly open about her bipolar disorder, her -bisexuality, her relationships and her suicide attempt would tell other journalists that her miscarriage is the one detail she regrets sharing. And I was the one who shared it.

Now, Halsey thinks back to how it all went down, the torrent of misogyny I’d brought upon her by writing about that intimate experience, one inevitably cast by the Halsey haters of the world as manipulative, attention-seeking, maybe even a lie: “It was just really weird, to see how people were like, ‘Well, I’m going to police the validity of this experience that she had.’ You know?”

I start to apologize, but she gently stops me. “I appreciate you saying that,” she says, “but definitely it had nothing to do with you and everything to do with the way people perceive the female experience.” By this point we’ve both gorged on her spicy rigatoni (perfectly spicy, worth the hype) under a huge, framed picture of Kurt Cobain at Reading and Leeds and have moved to the living room, where there’s a typewriter on the coffee table, a large crate for Halsey’s dog, Jagger, and a half-finished painting leaning against a column in the middle of the room next to a Polaroid camera and a palette of paint. (“I’m doing this series of paintings where watermelon is representative of this taboo female sexuality,” she tells me. “I know it sounds really weird, but I promise it makes sense.”)

In fact, the female experience is something Halsey’s been thinking about a lot, giving speeches at the Women’s March and other venues in which she’s referenced being sexually abused by a family friend when she was a child, forced into sex by a boyfriend when she was a teenager and sexually assaulted just a couple of years ago, something from which she’d assumed her fame made her immune. “Here’s what’s fucked up to me,” she says pointedly. “A young man seeks success and power so that he can use it to control people, and a young woman seeks success and power so that she no longer has to worry about being controlled.” But it turned out that even that problematic setup had been grossly optimistic, as her most recent assault taught her: “It’s an illusion, a fucking lie. There is no amount of success or notoriety that makes you safe when you’re a woman. None.”

Over lunch, she’d read me lyrics from her new single, “Nightmare,” scatting the words “Come on, little lady, give us a smile/No, I ain’t got nothing to smile about,” explaining how she was going to see Bikini Kill that night “to get some inspiration for my shows” and referring to the song as a “protest record,” which she thinks has been a long time coming. The actual song is not scatted so much as screamed, Nineties-alt-rock-style. “When was the last time you turned on the radio and heard a girl screaming, yelling, angry about something?” she asks. “That’s why I love Alanis. I want to turn on the radio and hear a young woman be like, ‘Fuck no!’ You know what I mean? Especially right now.”

Halsey. Photo: Paola Kudacki

Halsey confronted her recent sexual abuser, who she says “took it seriously, went to rehab, sought therapy.” She feels catharsis, feels confident that other women will not be at risk from the same person acting the same way. But she also understands — and resents — the risk she takes by speaking out at all. “Then I’m not ‘Grammy-nominated pop star,’ then I’m ‘rape survivor,’ ” she says with a shudder. “Uh-uh, no. Uh-uh, absolutely not. I have worked way too fucking hard to be quantified or categorized by something like that.”

Or even be categorized at all. Identity is a tricky thing for anyone, but especially for a pop star whose personality tends to shift, she says, to match whatever get-up she’s wearing. “I was talking to Dom the other day, and I was like, ‘When you’re laying in bed at night and you’re on tour and you miss me, how do you picture me? Do you picture me with short brown hair? Or long blond hair?’ And he’s like, ‘I don’t really know.’ ” And the thing is, Halsey doesn’t really know either. She can’t really picture what she looks like. “And I’ve thought about that for a while, and I’ve been like, ‘Is that a good thing or a bad thing?’ Does that mean I have no sense of identity? Or is it a good thing I don’t limit my perception because I haven’t permitted myself to view myself as one thing, because I haven’t stayed one fucking thing long enough to be that?” She pauses, considering, waiting for an answer to present itself. But of course no answer does.

“Are these Jay-z’s hangers? Or Patti Smith’s?” Halsey asks, eyeing a rack of them in the dressing room of Webster Hall in New York a couple of weeks later. “Why are there so many hangers in this room?”

“I feel like Jay-Z probably has more outfit changes than Patti Smith,” says her assistant Maria with a shrug. “But who knows?”

Halsey smiles, but then asks Maria for a Midol. Last night in her hotel room before going to sleep, she’d prayed “kind of, not to a god or anything,” that tonight’s show, her first headlining gig since last summer, would go well. Then she’d woken up to the immediate realization that she’d gotten her period, which was Not Good News. “I feel like for a normal female performer, she’s like, ‘Fuck, I have my period. I have a show today.’ And for me, it’s like, ‘Fuck, I have my period. I hope I don’t have to go to the hospital.’ ”

For a while, Halsey had been tormented by the idea that she wouldn’t be able to have children, that the endometriosis that could have caused her miscarriage would keep her from ever carrying a child to term. But surgery and some lifestyle changes have improved her health to the extent that her doctor no longer thinks she needs to freeze her eggs, which she had been planning to do this summer. “I was like, ‘Wait, what did you just say? Did you just say I can have kids?’ It was like the reverse of finding out you have a terminal illness. I called my mom, crying.” Halsey now jokes with Maria about having a “pregnancy pact” in which they agree to get pregnant together. “Never mind. I don’t need to put out a third album. I’m just going to have a baby,” she announces.

And, actually, that’s not so hard to imagine. When I met Halsey three years ago, her fame was acutely new and destabilizing, even for someone without a serious mental illness; for someone with one, there was a sense that the whole situation could go terribly awry, that behind her bluster, a real fragility was hiding out. Now that fragility seems to have morphed into a sort of tenderness, chaotic but kind. She no longer drinks hard alcohol, does drugs or smokes pot. “I support my whole family,” she says. “I have multiple houses, I pay taxes, I run a business. I just can’t be out getting fucked up all the time.” (She’s also profoundly amused by how much she can “freak out rich white men. Like, ‘Are you a fucking CEO? Same.’ ”)

Halsey. Photo: Paola Kudacki

Her only remaining vice is cigarettes, and she asks if she can light one now and then sits, pantsless in a ripped Marilyn Manson T-shirt, next to me on the sofa. I ask if, despite initial signs to the contrary, her success has been stabilizing. “Yeah, because it makes me accountable,” she replies carefully, taking a drag. “I’ve been committed twice since [I became] Halsey, and no one’s known about it. But I’m not ashamed of talking about it now.” Being committed isn’t a problem, she reasons, it’s a way of responsibly dealing with one. “It’s been my choice,” she continues. “I’ve said to [my manager], ‘Hey, I’m not going to do anything bad right now, but I’m getting to the point where I’m scared that I might, so I need to go figure this out.’ It’s still happening in my body. I just know when to get in front of it.” She quickly ticks off the people who work for her, tallies how many kids they have. “Do I want to hurt these people?” she asks.

Halsey says that the album she’s currently working on is “the first I’ve ever written manic.” Her ferocious writing process has been the same. “She’ll be like, ‘OK, I’m gonna go smoke a cigarette,’ and literally when she comes back the song is done,” marvels producer Benny Blanco. But because she “can’t sit still long enough to be productive,” she’s ended up giving herself perspective, walking away and then coming back to revisit songs weeks after she initially wrote them. An eclectic product of her state of mind, the album is a sampling of “hip-hop, rock, country, fucking everything — because it’s so manic. It’s soooooo manic. It’s literally just, like, whatever the fuck I felt like making; there was no reason I couldn’t make it.”

It’s also the first time Halsey’s work will not hide behind a concept, though there is, she says, a “motif.” “There’s a lot of exploration of l’appel du vide, which is French for ‘the call of the void,’ ” she’d told me back in L.A. “It’s that thing in the back of our minds that drives us to outrageous thoughts. Like when you’re driving a car and you’re like” — she mimics cutting the wheel — “or you’re on top of a building, and you’re like, ‘What if I just jump?’ ” That, she says, is what her manic periods are like. “You are controlled by those impulses rather than logic and reason.”

It’s getting close to showtime now. Halsey’s stylist comes in with a wig, black and blunt and a little tussled. For a moment, Halsey considers it. Tonight she will be performing her first album in its entirety, a sonic time warp for her hardcore fans. Should she have brought a blue wig, reminiscent of the Halsey of her Badlands days? “No,” she says, finally. “I can’t keep going back to that. Like, ‘This is the real me.’ I can’t deflect.”

Halsey used to pity “Ashley,” but she doesn’t now. “OK, point blank, here’s what it is,” she had said back in her living room, the late-afternoon light and the cigarette smoke bathing her in a soft-focus glow. “I was a teenage kid who wasn’t real well-liked in high school, and I was sold the dream that everyone was going to like me, because I was going to be a famous person.” But they didn’t, not everyone, no matter what persona she tried. “That’s all it is. And now I’m 24, and I’m like, ‘Well, I guess it doesn’t matter.’ ”

And, really, it doesn’t. Outside the dressing room, 1,500 misfits with blue hair and tattoos and teenage angst they can tap into no matter what their age are filing in to watch her sing a handful of songs she wrote back when she was still being sold the dream. They’ll sing along. They’ll scream her name. They’ll cry, most certainly they’ll cry, thinking about the bodies that lie next to them and the headlights in their eyes. And in that moment, however fleeting, the dream will be real, and the stories she tells will be true, and no one will feel like they have to apologize for any of it.