Next Gen: Ambi and Bindu Subramaniam On The Importance Of Music Education

The composers talk about introducing a music curriculum in government schools in Karanataka with the Subramaniam Academy of Performing Arts

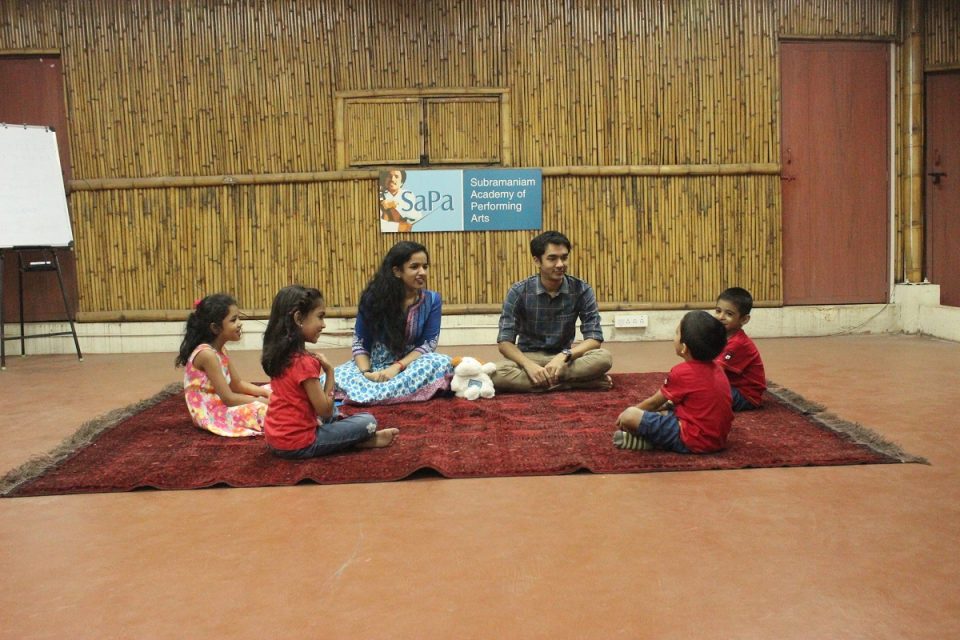

Bindu and Ambi Subramaniam (center) at one of their Subramaniam Academy of Performing Arts sessions. Photo: Courtesy of SaPa

Around 2007, when celebrated violinist and composer Dr L. Subramaniam’s music school launched, his children ”“ Bindu, Ambi and Narayana ”“ were taking on almost every role possible to chip in. Bindu Subramaniam recalls, “We were the janitors, the teachers, the administrators, and the managers. I remember when we once had a few visitors from France, the sump overflowed. So I was taking care of that while Ambi showed them around.”

They fully took on more responsibilities from from Dr. Subramaniam and singer-composer Kavita Krishnamurti in 2011, tasked with continuing a legacy of music and education. By 2016, Bindu says she and her brother took the conscious decision to “shift our focus to all-things-creative” with the Subramaniam Academy of Performing Arts (SaPa).

While the sibling duo are also working musicians, performing classical concerts as well as in fusion projects like The Thayir Sadam Project and SubraMania, the school remains in focus. SaPa runs through the Subramaniam Foundation, a non-profit organization. However, their SaPa in Schools program (launched in 2014 to “integrate music into the mainstream academic curriculum,” as Ambi mentions) is positioned as a business. Bindu adds, “To ensure that our program is available to children from underserved communities, we put a lot of the profit from SaPa in Schools back, and currently offer the program free of cost to 8,000 children. We try to achieve a balance between sustainability and as much outreach as possible.”

Bindu Subramaniam at a SaPa in Schools session. Photo: Courtesy of SaPa

SaPa in Schools ”“ in action since 2014 with private and NGO schools at first and then with government schools since 2017 ”“ trains kids in classical and western music. While they’ve had recent funding from the Infosys Foundation, the siblings’ most proud association is with Bengaluru-based Akshaya Patra Foundation, a not-for-profit organization responsible for one of the world’s largest school lunch program.

For music to serve as a means of empowerment can often be classified as idealistic. But Bindu says there needs to be awareness of the effects of music education. Her own personal anecdote involves an activity called Name Tango, where each child in the group sings their name out loud and the rest of the group repeats the name. Bindu noticed a stark difference between private and government school students in what is intended as an ice-breaker exercise. She recounts from a government school in Pune, “Children were mumbling their names and it was so incoherent that I had to stand right next to them to even be able to hear it. I realized that it was because their self-esteem was so low that they had trouble shouting their name out loud to a group. But when we encouraged them to continue the activity and they heard twenty others sing their name back to them out loud, there was a visible rise in their self-confidence.”

Ambi admits that one exercise doesn’t fix everything. SaPa have gone up against everything from electricity woes in schools to convincing parents that music was not a distraction “from learning subjects like math or science.” He disagrees about music as empowerment being an idealistic thought. “I definitely think that music will keep children from lesser privileged communities creatively happy, because the ability to create something of your own gives you power, one that can never be taken away from you. It can also be a great vocation; there are plenty of avenues in music that you can take.”